The following section on the 1745 Rebellion is an excerpt from the National Trust for Scotland pamphlet tided "Culloden." Whole books have been written about the Forty Five and you are encourage to investigate these sources for more details. For starters, I would direct your attention to the Osprey Campaign Series No. 12, Culloden 1746, The Highland Clans' Last Charge by Peter Harrington. A more extensive study of the final battle is found in John Prebble's Culloden (Penguin Books). Other titles of interest include Battles of the '45 and The Jacobite General (a biography of Lord George Murray) , both written by Katherine Thomasson. Kings Over the Water by Theo Aronson and Culloden and the '45 by Jeremy Black both provide extensive background information on the history of the Jacobite Cause and are highly recommended. The following, however, provides us with a concise summary of the Forty Five:

Had all gone as planned, the "Forty Five" would have been the "Forty Four", and a much more serious threat to George II. In February of that year, Louis XV planned a massive invasion of Britain. His objective was to place on the throne in London a monarch who would be ultimatly dependent upon France.

Ten thousand regular French troops were assembled at Dunkirk. The intention was to land them at Maldon on the Essex coast, within easy reach of London. But again weather intervened; a storm wrecked the invasion fleet, the expedition was abandoned. The young Prince Charles Edward Stuart who was to have sailed with it as the Prince of Wales and representative of his father, found that once his potential usefulness to Louis was gone he was virtually ignored.

He was not so easily put off, however. On July 16, 1745, he set out on what was virtually his own expedition. There were only two ships, the Du Teillay, a light frigate, and the Elisabeth, a larger frigate which carried 64 guns. The smaller ship was under the command of Antoine Walsk a noted privateer, and the Elisabeth, a ship of the French Navy, was on charter to Walsh. Aboard the Du Teillay were the Prince, seven supporters who have become known as the "Seven Men of Moidart," and a pitifully small store of arms and ammunition.

Off the west coast of Ireland the expedition encountered H.M.S. Lion, a British man-o'-war. She was engaged by the Elisabeth, and the Du Teillay slipped away to safety. But Elisabeth was badly damaged in the action and had to return to Brest. With her went the bulk of the military stores assembled for the Rising, and a company of French volunteers.

On Scottish Soil

The Prince's first contact on Scottish soil was not encouraging. On the Hebredean isle of Eriskay, Alexander MacDonald of Boisdale advised him to go home. "I am come home, sir," replied the Prince. On July 25, the Du Teillay reached the Scottish mainland at Loch nan Uamh near Arisaig. The Prince sent out letters to Highland chiefs seeking support, and at Glenfinnan, on August 19, the Standard was raided, his father proclaimed James VIII and III and the Prince himself as Regent. The "Forty Five" had begun.

It was a small force at first, only about 1,200 men. More than half of them were Camerons, under their acting-chief, known to history as the "Gentle Lochiel." (The chief, his father, was in exile.) Most of the remainder were Macdonalds of Keppoch.

They gathered strength as they moved eastwards, avoiding Fort William and Fort Augustus which had Government garrisons and crossing by the Corrieyaiffick Pass into Badenoch, ironically by one of the roads built by General Wade to discourage Highland insurgency.

A Government army under Lieut.-General Sir John Cope was hurried north. Cope, however, chose not to meet Charles, but marched instead to Inverness, leaving the route south to Edinburgh open to the Jacobites. At Perth, the Prince was joined by Lord George Murray (brother of the Duke of Atholl) who was to prove his outstanding field commander. The Adjutant and Quartermaster to the Army, John William O'Sullivan, an Irish soldier of fortune and one of the "Seven Men of Moidart" was to be a thorn in Lord George's side during the ensuing campaign, and responsible for much of its failure.

But these problems lay in the future. Edinburgh was entered virtually unopposed on September 17, though the Castle remained in Government hands. The Prince occupied the Palace of Holyroodhouse, home of his ancestors.

Master of Scotland

Cope, meantime, had marched to Aberdeen and taken ship to Dunbar. He moved towards Edinburgh, but on September 21, in less than ten minutes, his army was routed at the Battle of Prestonpans. Charles, magnanimous and humane in victory, was master of Scotland. But it was not enough. The march on London began on November 1. Carlisle surrendered on November 16; on the 28th the army reached Manchester, and, on the evening of December 4, Darby.

All was not well however. Support from England had been disappointing; Charles and Lord George Muff ay had quarrelled; about a thousand Highlanders had quietly left to return to their native glens: three Government armies were threatening to converge on the Prince's force.

Charles was all for continuing to London, only 127 miles away, but on December 6 - "Black Friday" - the decision to retreat was taken. It may have been wrong. There was concern, possibly panic, in London. There was, at last, the prospect of support from England and Wales; 10,000 French troops were said to be embarking at Dunkirk. A rapier-like thrust at the capital could conceivably have succeeded; but speculation is pointless.

Dispirited, they faced the long road back to Scotland. Glasgow was reached on Christmas Day. The city was ill-disposed. Only Lochiel's intervention, it is said, saved it from being sacked - a circumstance which in later years, tradition says, led to the bells being rung whenever the chief of Clan Caineron entered the city. Sterling town surrendered, but not the castle. Reinforcements arrived, including 400 Mackintoshes raised by Lady Mackintosh, whose husband, head of the clan, was on the Government side. Men, stores and ammunition arrived from France.

Battle of Falkirk

From Edinburgh, Lieut.-General Hawley marched to relieve Sterling. The battle of Falkirk on January 17, 1746 was a victory for the Prince's army, but in the confusion of a winter dusk the advantage was neither realized nor exploited. Hawley retired to Edinburgh, there to hang his deserters on gallows erected in anticipation of Jacobite rebels.

On February 1, after some acrimony among the leaders, the Highland army forded the Firth of Forth and headed north. At first, the Prince had been unwilling to accept Lord George Murray's advice, preferring that of O'Sullivan, who wanted him to fight and win another Bannockburn. On the way to Inverness, the Prince had a narrow escape while being entertained at Moy Hall by Lady Mackintosh. Lord Loudon, who held Inverness for the Government, mounted an expedition to capture the Prince. A handful of Moy men, however, succeeded in the darkness, in convincing the raiders that they were running into the whole Jacobite army. The result was the "Rout of Moy". For seven weeks of winter weather, Inverness was the Prince's Base.

The Duke of Cumberland, second son of George II had reached Aberdeen on February 27, 1746. His army was already strong and received additional reinforcements, including 5,000 Hessians. These latter troops remained in the Dunkeld area, blocking the rout to the south. There were sporadic, dispersed actions during the weeks of waiting for better weather. The Jacobites took Fort Augustus, and near Dornach, defeated Lord Loudon, who had retreated there from Inverness.

Cumberland left Aberdeen on April 8. Jacobite intelligence of his movements was sadly lacking. Six days later he was in Nairn, although Charles had only just learned that he had crossed the Spey some 30 miles further to the east. On Monday April 14, 1746 the drums beat and the pipes sounded in Inverness to assemble the army for battle. Not all were on hand, however. Messengers were sent out to recall those on forays elsewhere. Next day, on the moor which was then called Drumossie but is now Culloden, the army was drawn up in the order in which it was to fight the coming battle, still 24 hours away.

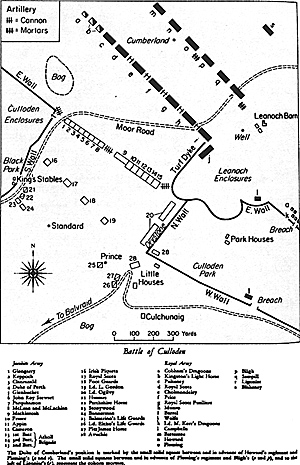

Map of Battle of Culloden

More Origins of the Jacobite Rebellion 1745

- Introduction

Dundee's Rising In 1689

The Old Pretender

The Great Rising of 1715

The Little Rising of 1719

The "Forty Five" (1745)

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VI No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com