It was Christmas Day 1745 and Lord George Murray led a tired and

dispirited vanguard of the Jacobite army into the city of Glasgow. The

following day the Prince -- H.R.H. Charles Edward Stuart -- Prince of Wales

in the Stuart Succession, entered with the balance of the Jacobite forces.

It was Christmas Day 1745 and Lord George Murray led a tired and

dispirited vanguard of the Jacobite army into the city of Glasgow. The

following day the Prince -- H.R.H. Charles Edward Stuart -- Prince of Wales

in the Stuart Succession, entered with the balance of the Jacobite forces.

The army had covered 580 miles since leaving Edinburgh on October 16, and in the interim had laid siege to, captured, and later lost the fortress of Carlisle, had marched as far south as Derby, only 130 miles from London, had executed a skillful retreat in the midst of hostile country, and won, on the field of Clifton, the last battle to be fought on English soil.

Yet all these accolades could not hide the bitter truth: the massive French invasion promised by the Prince and Louis XV had not arrived. A combination of bad weather, poor timing and a lack of resolve all combined to seal the invasion's fate. To put it bluntly, the Prince's followers had come to the realization that they were on their own. This was the cause of the Jacobite retreat from Derby.

Army Review

The Prince reviewed the army on Glasgow Green on January 2, 1746 and the next day advanced the Jacobite army to Stirling Castle, not far from the historic field of Bannockburn. The Castle was besieged under the direction of an incompetent French engineer, Mirabel de Gordon, who had recently arrived from France along with Lord John Drummond and a small contingent of French troops.

They consisted of approximately 300 men from the Royal Scots Regiment (a regiment of Scots exiles in French service), a contingent of picquets, 50 men each of the Irish Regiments Lally, Ruth and Dillon; and about 80 men of the Irish Regiment of FitzJames Horse. No one else had gotten through the British blockade.

As the Jacobites prepared their encampments and the French, the siege parallels and battery, Lord George Murray and 5 battalions of foot were sent on outpost duty at Falkirk Hill by the Prince. The date was January 11, 1746. Due to the bad blood between the Prince and his Lieut.-General, Lord George was not permitted to take his own Atholl brigade with him. Unfounded rumors by jealous members of the Prince's staff had told him that Lord George intended to defect with the entire Atholl brigade of three battalions at the first opportunity. The Prince kept the Atholl men as his headquarters guard.

On January 13, Lord George marched from Falkirk to Linlithgow (in the direction of Edinburgh) to slow the advance of the Government army and its new commander, former dragoon commander Henry Hawley. This general owned the unenviable nickname "Hangman" because he was a fierce disciplinarian who hung men with little provocation. Hawley held the Jacobites in utter contempt as a military force. A veteran of Sheriffmuir in the 1715 Rising, he had been posted with the Government cavalry on the left and had subsequently developed a false impression that Highlanders could not stand up to a cavalry charge.

Hawley's picquets retired as the Jacobites entered Linlithgow and pursued. Murray knew that he must determine Hawley's intentions and without cavalry, he had to press with his entire force or risk being defeated in detail. He was unable to bring the government patrols to stand and so he withdrew back to town to remove the supplies that Hawley's troops had abandoned.

Murray's picquets brought back reports of a sizeable government advance of horse and foot, near Bathgate, a short ways away. Murray ordered the pipers of all regiments to play and give the impression that the entire Jacobite force intended to advance. After destroying what supplies could not be carried, the Jacobites retreated to Falkirk. Hawley's cavalry pursued them as far as Linlithgow bridge. There, a sharp verbal battle developed as both sides attempted to taunt the other to attack.

The attempt to trap the government forces failed. Four regiments of foot, two of horse and two battalions of militia returned to their main body, as did the Jacobites.

Reinforcements

Lord George billeted his command on Bannockburn Field and reported the day's events to the Prince. Hawley still intended to relieve the siege of Stirling Castle and to thrash the rebels in the field at the same time. He even erected gallows in Edinburgh in anticipation of his victory over the Jacobites. Unknown to Hawley, the Jacobites were receiving strong reinforcements from the north which, between the nineth and the fifteenth of January, nearly doubled the size of the Prince's army to 9,000 men. Never before had the Jacobites fielded an army of this size.

Knowing this, Lord George recommended an immediate advance before the Duke of Cumberland's 8,500 men and 5,000 Hessians under the Prince of Hesse-Cassel could join Hawley's 8,400 men. A victory over Hawley would enable the Jacobites to turn on the other two Government forces and defeat them in detail. Excluding a covering force left behind at Stirling, the two forces were all but equal in numbers, but the Prince, influenced and corrupted by his Irish advisors, procrastinated. On the fifteenth, reports arrived of a Government advance and so the Jacobites deployed on Plean Muir, two miles SE of Bannockburn. The report proved false.

The same occurred on the sixteenth and again the reports were inaccurate. Although there was some movement in the Government camp, it was simply the arrival of Hawley's main body which trailed in by early afternoon. Hawley now had 12 battalions of foot, two battalions and one independent company of militia, three regiments of dragoons and a full artillery train. His. failure to recognize the advantages of the terrain, his failure to post proper patrols, and most importantly, the contempt he held for his enemy, were about to come together all at once.

Lord George advised the Prince of the need to advance on Hawley before the latter could advance upon them. This time, Murray applied a logic that the Prince's advisors could not dispute. Hawley's army was but four miles away and equipped with tents. The Jacobites, on the other hand, were quartered in the surrounding villages, making it next to impossible for them to assemble before midday. This had been demonstrated by the two earlier false alarms. If the Government troops broke camp at dawn, they would be in the midst of the dispersed Jacobites before they could assemble for battle. If Hawley's dragoons could delay the most outlying Jacobites, then his main force of 12 battalions and the artillery train could defeat the balance of the Jacobite army in detail.

To March

For once, the Prince responded to Murray's cold logic with decisiveness! By 1 PM the Jacobite army was in motion to strike at Hawley. Left behind were 1,200 men to cover Stirling Castle. The Prince's banner was even left behind to further enhance the ruse. The Prince's army crossed the Carron River at the steps of Dunipace, assisted by a local guide, and began to ascend the hill of Falkirk in two columns, two hundred paces apart.

Meanwhile, General Hawley was at his headquarters at Callendar House, three-fourths of a mile from the front. Lady Kilmarnock, General Hawley's "host", was the wife of Lord Kilmarnock -- commander of Prince Charles' body of life guards. She did her part in keeping the General well-fed and "watered" from her ample wine cellar. She played no small part in detaining Hawley from his camp until the last possible minute.

Lord John Drummond advanced at the head of the Royal Scots, Irish Picquets and all the Jacobite cavalry as a decoy down the main road from Bannockburn to Falkirk, passing north of the Torwood, from which point they would become visible to the Government camp. They had departed well in advance of the main body of clan regiments and were spotted by 11 AM. Couriers went out to Hawley and the camp to sound the alarm to stand to. Surprisingly, they stand down fifteen minutes later. Hawley dismissed the report as a Jacobite probe or forage party and continued his "tea party" with Lady Kilmarnock and his staff. Drummond's advance guard rejoined the main army on seeing the Government forces standing to arms.

At 1 PM, however, two civilian riders burst into the camp of the Third Regiment of Foot (The Buffs) and announced that the Jacobites had crossed the Carron and were about to fall upon them. The British soldiers tried to drive these messengers out of camp, after all, they had heard the same cry of wolf earlier in the morning. The regimental commander, Colonel Howard, climbed a tree with his spyglass and what he saw chilled him more than the damp January air.

The Jacobites were coming indeed, forming up by battalions and in greater numbers than imagined. Hawley's second-in-command, Major General John Huske, ordered the "stand to" once again and sent his personal ADC to carry the warning to Hawley. Hawley was shocked and ran from the house cursing and blaming everyone but himself for the predicament. Galloping all out, Hawley arrived hatless two minutes later and ordered an immediate advance of the dragoons to seize and hold Falkirk Hill until the infantry could secure it.

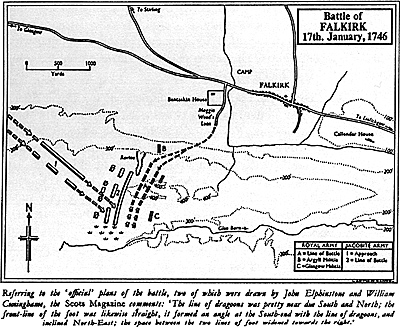

At this point, the poor state of staff preparedness became evident in the Government camp. This was the first time that Hawley had seen the probable field of battle. Knowing the Scots preference for high ground, he made no effort to seize it and disrupt possible Jacobite plans to do likewise. The map below depicts the deployment of both armies prior to the commencement of the battle.

Map of Battle of Falkirk

More Falkirk Campaign of 1746

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VI No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com