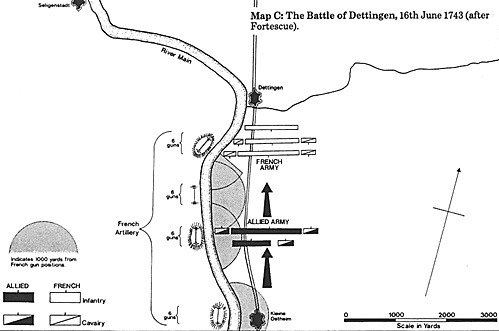

The British contingent of the Pragmatic Army had deployed on the left, with the Austrian infantry brigades in the center, and four battalions of Hanoverian infantry and some British cavalry on the far right, next to the woods. A second battle line of similar proportions deployed behind the first line. The British and Hanoverian Guards protected the baggage train and more Hanoverian cavalry formed the rear-guard.

The weak spot in the allied line was on the extreme left, flanking the Main River. A lone regiment of cavalry, Bland's Third Dragoons, had been ordered up by General Clayton (the left wing commander) to fill the gap between the end battalions on the left and the Main. These latter units were Johnson's 33rd Regiment in the front line and Bligh's 20th Regiment in the second line. Bland's two squadrons faced nine squadrons of the Maison du Roi. Clayton sent urgent requests for more cavalry to face this threat.

While Bland filled the gap on the left, the allied line advanced forward at a slow pace. Some regiments were reportedly knee-deep in mud. They halted to dress ranks and a few battalions opened a nervous and ineffective fire (without orders) on the parading Maison du Roi. The pop-pop of musketry frightened the King's horse, which bolted off to the rear, out of control. Eventually, the horse was brought under control and the King remained dismounted for the rest of the battle.

The infantry fire ceased, order was restored, and weapons were reloaded. At this point, the Gardes Francaises advanced towards the British portion of the line and fired off a ragged volley of musketry. The British response was more effective this time and the Gardes retired behind the protection of the Maison du Roi. Throughout the day, French infantry would advance in piecemeal fashion up to the British line and would be repelled by British musketry. After the battle, Marshal Noailles wrote to King Louis XV that,

- "I would never have believed, Sire, what I saw yesterday. Their infantry drew up in close order and stood like a wall of bronze, from which there issued so quick and so well-sustained a fire that the oldest officers confessed that they had never seen anything like it, incomparably superior to ours."

-- J.A. Holding French Arms Drill of the 18th Century

From the British perspective, the initial firing at the Maison du Roi was likened to a "feu de joie" by their officers and represented a lack of discipline that prevented them from employing the disciplined platoon firing system that we associate with the British infantry of this period. James Wolfe, then an officer in Duroure's 12th Regiment, admits that he and his regimental major spent most of the day ordering their men not to fire indiscriminantly. Lt. Colonel Charles Russell of the 1st Foot Guards wrote:

- "The infantry were under no command by way of Hyde Park firing, but the whole three ranks made a running fire of their own accord. .. with great judgement and skill, stooping all as low as they could, making almost every ball take place ... The French fired in the same manner.. .without waiting for words of command, and Lord Stair did often say he had seen many a battle, and never saw the infantry engage in any other manner."

--J. A. Holding Fit For Service

One battalion officer asked General Clayton whether he should fire at the French by platoons or ranks, to which Clayton replied, "as to platoon or rank firing I shall be glad to see you perform either in action, but I own I never did yet on a field day or at a review."

In other words, controlled firing was difficult to achieve in practice, much less under battle conditions.

Cavalry Action On The Left

The outcome of the battle would ultimately be decided on the British left. Here, the Maison du Roi outnumbered Bland's Dragoons, nine squadrons to three squadrons, and were supported by another line of French line cavalry. The Maison du Roi was the elite of the French cavalry and if they could break through Bland before cavalry reinforcements arrived, then the entire left flank of the allied line would be exposed to their fury. The action began with a premature charge by two squadrons -- the Seconde Compagnie des Mousquetaires Noirs and the Compagnie de Chevaux Legers de la Garde. Bland promptly counter-charged and cut his way through both units. General Clayton directed Johnson's Regiment (33rd), on the far left of the front line, to fire half of his platoons at the Mousquetaires and Chevaux Legers, and the other half at the Gendarmes and Carabiniers, who were supporting the first charge. The latter regiments were about to charge the two units to Johnson's right, the 21st and 23rd Fusilier regiments.

- "The 33rd faced the attack boldly, never giving way for an inch, and brought men and horses crashing down by their eternal rolling fire."

-- Fortescue

Bland's Dragoons would face two more charges, after which the regiment was practically annihilated, but they had bought enough time for the British cavalry reinforcements to arrive on the scene. The 1st (Honeywood's) and 7th (Ligonier's) Dragoons galloped upon the Maison du Roi, but were repulsed by French steel. Fortescue suggests that both regiments attacked haphazardly, without forming up for the charge. The Blues were the next unit to arrive on the left and they too were turned back by the Maison du Roi.

While cavalry crossed swords with one another, the French Gendarmes and Carabiniers advanced towards the two fusilier regiments at the trot, pistols in both hands and swords dangling from their wrists. The French riders discharged their pistols and threw the empty weapons at their foe; then they charged the fusiliers and were repulsed by musket fire.

The Gendarmes formed up for a second charge, but were intercepted by the aforementioned charge of the British 1st and 7th Dragoons. As the British cavalry fell back, they became entangled with the Blues. The swirling mass of horses fell into the ranks of its own infantry. Seeing this confusion, the Gendarmes rallied and thundered down upon the disordered British foot (33rd, 21st, and 23rd regiments) and broke through the redcoats' lines.

The fusilier regiments recovered quickly, however, and turned inward on the French cavalry and shot them down in bunches. Reinforcements of allied horse continued to arrive on the left and helped to close off this gap in the British line. The 4th and 6th Dragoons and two regiments of Austrian dragoons attacked the Maison du Roi, were repulsed twice, but finally succeeded in driving the courageous French from the field. Certainly, the Maison du Roi's fine reputation was well-earned at Dettingen.

Defeat Turns To Rout

The battle was effectively over for the French once the Maison du Roi was defeated. The French infantry in the center and right could make no headway against the allied line. The first French line had attacked and had been repulsed in detail and the second line, seeing the effect of battle on their comrades up front, could not be persuaded to advance.

There was one final incident in the battle that deserves mention. At one point, the Mousquetaires Noirs disengaged themselves from the cavalry melee on the left and without warning, galloped down the length of the opposing battle lines to the allied right. They were shot at and cut to pieces, then finished off by British and Austrian cavalry. There is a theory that the Mousquetaires Noirs were trying to earn a reward that Noailles had offered to any unit that captured the British sovereign, who happened to be on that part of the field.

The Austrian general Neipperg then ordered the allied cavalry on the right flank to fall upon the French left. The entire French left caved in and panic spread amongst the French army as it ran off the battlefield towards the two pontoon bridges at Seligenstadt. The crush of men caused one of the bridges to collapse and scores of men drowned in the Main. Even the Gardes Francaises threw down their weapons and bolted towards the Main, preferring to swim rather than fight. Hundreds of Gards drowned in this manner and for this, they earned the nickname of "Canards du Mein" , or "ducks of the Main".

The French left 6,000 killed and wounded on the battlefield, while allied casualties numbered some 3,000. Included in the booty was the standard of the Chevaux Legers, captured by the Scots Greys. The entire battle lasted six hours and left the allies too tired to pursue their routed foe. Instead, they camped on the battlefield and continued back to their supply base at Hanau the next day.

Noailles' sure victory had been snatched from his hands by the impetuous Grammont. Even after leaving his strong defensive position, Grammont might have won had it not been for his own and his officers' inabilities to form a battle line and coordinate the attack. Marshal Noailles recognized these deficiencies in the French officer corps and wrote to Louis XV that:

- "The manoeuvers of yesterday were due to the enemy's discipline alone, and to their officers' strict subordination and obedience to commands. I am grieved to inform your Majesty that these qualities are unknown among our own troops, and that, unless we apply ourselves with seriousness and perseverence to remedy this evil, your army will be utterly ruined."

-- Pajol, Les Guerres sous Louis XV

These same problems would continue to plague the French army well into the Seven Years War, but for now, a brief respite was at hand, for France now turned the remnants of Noailles' army over to Maurice de Saxe. Under Marshal Saxe, French military prowess would have one more moment of success in the Austrian Netherlands (1744 to 1748) while British fortunes in Europe would sink to an all-time low under generals such as Lord Stair, Wade, and Cumberland.

Battle of Dettingen: June 27, 1743

- Historical Background

Battlefield Terrain and Deployment

The Battle of Dettingen

Wargaming Dettingen

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VI No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com