Early in May, news reached Chrudim that Prince Charles of Lorraine was advancing towards Prague with an army of 30,000 Austrians. This was a ruse, for in fact, the Austrian command had decided that Frederick was its most dangerous enemy and all efforts would be made to isolate him and defeat him. Charles' plan was to drive between Frederick's army and the allied army in Prague, threaten his supply depot in Koniggratz, and bring the Prussians to battle. Frederick fell for this deception and marched west from Chrudim with an advance guard of 10 battalions and 20 cavalry squadrons. Prince Leopold (the Young Dessauer) was to follow the king with the rest of the army, some 18,000 men, once the bread wagons arrived from Koniggratz. Food supplies were getting very low.

During the course of this march, Frederick had observed a large body of Austrians to the south of him and believed this be General Lobkowitz's corps of 8,000 Austrians. In fact it was really Charles and his entire army. Frederick made camp at Kuttenberg, a few miles west of Chotusitz on the night of May 16. That same day, Prince Leopold brought the rest of the army to Chotusitz, and from the same vantage point used by Frederick the day before, saw a large Austrian encampment on the plain below. Leopold counted the rows of tents and estimated that there were nearly 30,000 men, i.e. Prince Charles' army and not the smaller detachment observed by Frederick. Deserters informed Leopold that the Austrians were advancing on Chotusitz, so Leopold remaind there and invited the king to join him as soon as possible. Frederick promised to reach Chotusitz by the next morning with his men and ample supplies of bread.

The Austrians Attack Leopold

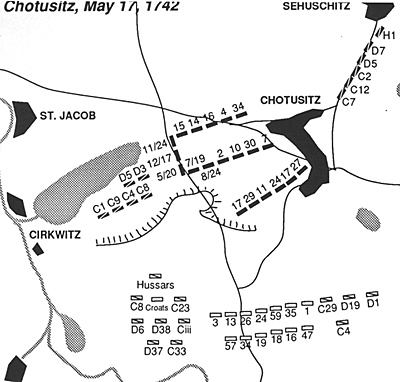

Charles ordered a night march to Czaslau, a small hamlet two miles south of Chotusiz. Three long columns marched through Czaslau around 4 A.M. and prepared to attack Leopold. The battleground was fairly flat, some four miles square with two streams on the eastern flank, the Brslenka and the Dobrowa. A collection of ponds and quagmires framed the western flank of the battlefield. Chotusitz lies in the middle of all of this soggy terrain.

To the south and west of the town, a plateau of about 20 meters in height,intersects the road from Czaslau to Chotusitz. A traveler would have to ascend this plateau before becoming aware of the large Cirkwitz Pond to the west and the town of Chotusitz to the east. There was another low rise just north of the pond that obscured the road from Kuttenberg to Chotusitz, meaning that Frederick could arrive undetected.

Leopold established his camp and baggage park north of the town and early that morning (6 A.M.) he became aware of the fact that the Austrians were forming up for a battle. The following passage from Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma by Robert Asprey, describes Prince Leopold's battle preparations:

- "Leopold rides to his commanders. He orders General Wilhelm von Buddenbrocks cavalry to deploy behind the heights on the right with the flank anchored on Cirkwitz Pond. His heavy artillery - only four guns - is moved to a hill fronting Buddenbrock's position. Kalkstein's infantry will deploy on Buddenbrock's left to carry the line to Chotusitz. Leopold rides east, picks up Lieutenant General Adam Friedrich von Jeetze and canters to the flatland north of Druhanitz. Jeetze is to deploy his infantry here, the right resting on Chotusitz, the left tied in with General von Waldow's cavalry, which will carry the line to the deer park by Sehuschitz. Once deployment is carried out, the heavy guns on the right will open fire, Buddenbrock's cavalry will attack, the infantry will follow Leopold returns to the right wing, sends the king a report of his deployments and intentions. It is about seven A.M."

"The troops are tearing into thick loaves of bread when Leopold s orders reach subordinate commanders. The men are still tired, unfamiliar with the land; there is confusion. Troops grudgingly shuffle into formation. Tents are left standing. Matters go well on the right, where heavy guns are brought up and unlimbered, where Buddenbrock's squadrons deploy in defilade, almost completely hidden by undulating terrain to their front. But matters are not so prosperous with the infantry. Kalkstein's battalions are slow in forming lines on Buddenbrock's left. Jeetze apparently misunderstands his orders. Leopold wants four infantry battalions in line east of Chotusitz Jeetze places only one battalion here and three battalions on the heights south of the village. Marshy terrain slows the deployment of men and horses. More delay. Dangerous gaps open east of Chotusitz. Kalkstein s battalions move slowly. Another gap opens west of Chotusitz."

The Prussians opened the battle at 7:30 A.M. with a cannonade from four 12 pound guns on their right flank. Their target, as at Mollwitz, was the Austrian left flank cavalry which was forming on the plateau overlooking the Cirkwitz Pond. The artillery fire disordered the Austrian hussars in the forefront and so they withdrew a short distance, leaving a gap between the the of their cavalry and their infantry on the left flank.

Buddenbrock ordered his first line to attack -- four regiments of armored curaissiers advanced in a tight, boot to boot formation, first at a trot and then at a gallop over the final yards. The impact drove off the first line of Austrian light cavalry and Rothenburg's second line of Prussian dragoons scattered the second line of Austrian horse, which fell back to Czaslau. So far things were looking good for the Prussian cavalry. There would be no repeat of the dismal performance of the Prussian cavalry at Mollwitz, they thought.

By now the dust from a thousand hooves filled the air and blinded all as Buddenbrock tried to reform his cuirassiers for another charge. However, three Austrian cavalry regiments came charging out of the dust clouds and struck the stationary Prussian horse in the front and flank. Meanwhile, Rothenburg's supporting dragoons lost their bearings in the dust storm and veered too far to the left, where they tumbled into the Austrian infantry holding down the left flank. The soldiers held firm and as Rothenburg tried to rally his dragoons, he too was attacked by Austrian heavy cavalry from all directions. His dragoons were cut to pieces.

It was now 8 A.M. and Frederick had arrived with the remaining eight battalions of the Prussian vanguard and formed them into a second line behind Kalkstein's troops on the Prussian right. The king could not determine the outcome of Buddenbrock's attack because the cavalry melee was entirely enveloped in the clouds of dust.

Things were not going well for the Prussians on their left either, around Chotusitz. Jeetze had moved his infantry in front of the town, dangerously exposed with its right flank hanging in the air. To his left, the swampy ground around the Brslenka stream separted von Waldow's supporting cavalry from the Prussians in front of the town. Von Waldow moved forward to attack, but his cavalry had to pick its way through the swampy ground very gingerly, and as they advanced they were attacked by Austrian cuirassiers. The two lead regiments of von Waldow's brigade, CR7 and CR12, were roughtly treated by the enemy.

Now the Prince Wilhelm Regiment of Prussian cuirassiers, the famous yellow jacketed "Gelbe Reiters" came to the rescue. Picking up the survivors of the other two regiments, they hacked their way through four regiments of Austrian cavalry and then galloped southwest behind the Austrian army to join Buddenbrock's melee on the Austrian left. During the course of this three mile ride into oblivion, the Gelbe Reiters rode down two infantry regiments and captured a flag. The eight surviving officers of the regiment received the Pour-le-Merite award from Frederick after the battle.

Jeetze was still having problems on the left, despite the courageous, but stupid charge of the Prussian cuirassiers. Their disappearance allowed the Austrian cavalry to reform and threaten the Prussian left. The Prussian dragoons of the second line attacked this body of Austrian horse, but they were outclassed and sent reeling back towards Chotusitz. Jeetze now had no cavalry support on either flank and the peril of his position in front of the town was quite evident to both sides. He attempted to plug the gap on his left, caused by the rout of the dragoons, by extending three battalions east of the village towards the Brslenk Stream.

On the opposite side of the field, Prince Charles and his advisors could see that now was an opportune time to attack the Prussian left with infantry. Austrian artillery advanced and unlimbered before the town and poured a hot fire into the Prussian line. Then five regiments of infantry advanced on Chotusitz. They stopped to fire, then surged forward with levelled bayonets. The battle now broke down into a tangled mass of troops in desperate house to house fighting in the town. By 9 A.M. the Prussians were forced to abandon the town when some enterprising Austrians set fire to a number of the thatched roof buildings.

Meanwhile, Austrian cavalry worked its way through the Brslenka Stream east of the town and moved into a position to the north to intercept the the mob of Prussians that were streaming out of Chotusitz. Werdeck's regiment of Prussian dragoons (DR7) tried to check the Austrian cavalry, but they were badly mauled, losing 516 men (killed, wounded and captured) in all. The remaining Austrian cavalry north of town now turned its attention on the Prussian encampment, rather than continuing its pursuit of the disorganized Prussians. Booty is better than battle and they paid no attention to the threats and screams of their officers. This brief respite gave Leopold some time to form a new defensive line north of the town. At the same time, he was probably wondering when Frederick was going to commit the 21 fresh battalions of infantry that were lurking in the hollow on the right flank.

Yes, where was Frederick?

He was hiding in the aforementioned hollow waiting for the outcome of Buddenbrock's cavalry fight. By 9:30 A.M. the dust was finally beginning to settle and dispersed squadrons of Prussian cavalry were riding off towards Kuttenberg, followed by pursuing Austrian cavalry, which no longer posed a threat to Fredeerick's infantry. Robert Asprey describes what happened next (Ibid, page 257):

- "With the Prussian left absorbing Austrian fury, with the Prussian right intact, Frederick orders twenty-one fresh battalions to attack. They come from behind him. Heavy guns pave the way as their troops march out rapidly in precise lines. They advance several hundred yards to the heights, wheel left. Now battalion 3-pounders fire from front and from intervals between battalions. It is total surprise. The Prussians, marching like automatons (Editor: aren't you getting tired of this cliche?), strike the Austrian left, shatter the protecting regiments, hurl them back on center and right. Leopold on the left exploits the surprise, orders a fresh attack. Prussian bayonets drive an astounded enemy from Chotusitz. Frederick's oncoming battalions loom like an anvil against which Leopold can hammer the enemy. Charles and his generals recognize the danger. Their attack has failed. They are in terrible trouble. They retreat."

The battle was over by noon. An Austrian rearguard of a few battalions, guns and cavalry held the stone bridges across the Brslenka Stream between Chotusitz and Czaslau while the rest of Charles' army retreated south. They abandoned ten munition wagons and seventeen guns to the Prussians and lost 6,300 men, including nearly 1,000 prisoners. Prussian casualties of all kind were 4,800, including 2,560 cavalry casualties.

The consequence of the battle was that Maria Theresa was more receptive to Frederick's peace overtures, with the English diplomat, Lord Hyndford acting as the intermediary between the courts of Vienna and Berlin. Austria needed to concentrate her best troops, those facing the Prussians, against the two Franco-Bavarian armies that threatened her empire. This would be possible if Prussia were out of the war. Preliminary terms were agreed to in June and on July 28, 1742 both parties signed the Treaty of Breslau to end the First Silesian War. Austria formally ceded Upper and Lower Silesia and the County of Glatz to Prussia.

This was an important gain for Prussia. As Christopher Duffy explains, "by 1752 Silesia yielded more than one-quarter of the state revenues, and out of all the Prussian lands it was to make by far the greatest single contribution (18 million thaler out of 43 million) to the cost of the Seven Years War.

Battle of Chotusitz May 17, 1742

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VI No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com