In January, 1711, Augustus summoned Maurice home from the war in Flanders. Maurice must have gotten a very good 'performance review' from his superiors, because his father was pleased with him and he was greeted in Dresden with the greatest joy and approbation. Maybe he was more heavily engaged while in Flanders than the reader has been led to believe. Anyway, even Marie-Aurora, who accompanied her son to Dresden for the glorious occasion, was welcomed back to court (briefly).

It was at this time that Augustus finally acknowledged Maurice as his son, and raised his annual allowance to ten thousand thalers-—still not enough to get the lad out of debt, but helpful. The King also gave Maurice the rank of Graf von Sachsen. History knows Maurice by the French form of this title, Comte de Saxe. As further evidence of Augustus's regard, Maurice was named colonel of a regiment of cuirassiers. The boy's apprenticeship at arms was apparently considered complete, and at age fourteen he was a full-fledged soldier commanding a large force of cavalry. He would soon get to command it in action.

The interminable Great Northern War still dragged on in 1711. It would not end until 1721, though its decisive phase had occurred while Maurice was on his way to Flanders in 1709, and the Saxons had nothing to do with turning the tide. The terms of the treaty of Altranstadt, which Augustus II had been compelled to sign in 1706, had knocked Saxony out of the war in most humiliating fashion. But the tide was turning.

In 1708 the overconfident and exceedingly rash Swedish king, Charles XII, had invaded Russia, hoping to knock Peter the Great and his rabble into submission once and for all. It did not work out that way. On 28 June 1709, after numerous misfortunes had weakened his army, Charles assailed a much larger Russian force, commanded by Peter himself, near the town of Poltava. The Swedes fought with their usual ferocity, and for a time the issue was in doubt. The Russians had strengthened their lines with redoubts, and the furious Swedes took many of them. Ultimately, however, numbers prevailed. A desperate charge by 7000 determined Swedish infantry failed to break the Russians, and disaster ensued as most of the remaining Swedish force was either cut to pieces by the counterattacking Russians, or surrendered.

The wounded Charles fled south at the head of a few hundred horsemen, only to be captured and held prisoner for years by the Turks. Charles was a "never say die" sort of guy, and would eventually reappear later in the war and would fight brilliantly until killed in action, but the defeat at Poltava and his subsequent capture was the beginning of the end of the Swedish Empire in Europe. Sweden's brief tenure as a great European power was drawing painfully to a close.

Naturally, the opportunistic Augustus the Strong took full advantage of the disaster that was engulfing the Swedes. In 1709 he repudiated the treaty of Altranstadt and declared himself once again King of Poland. However, it was a Russian army that actually invaded Poland and toppled Stanislaus Leszczynski, the Swedish puppet, from the throne. Although Augustus was again on the throne, he was now a client of Russia, dependent upon Peter the Great to retain his kingdom.

Late in 1709 a Polish-Saxon army moved into Swedish Pomerania to support the Danes, who had overrun the former Swedish possessions of Bremen and Verden, and had even invaded southern Sweden. Augustus contemplated a quick victory in Pomerania, but as usual his military perspicacity was flawed, and the Saxons found themselves in a vicious brawl. The Swedes fought on with the wonderful tenacity of a wounded and cornered lion. The Danish invasion was defeated at the Battle of Helsingborg (February, 1710). In Pomerania the Saxon-Polish forces had their hands full as they unsuccessfully struggled to wrest control of the region from fast moving and hard hitting Swedish contingents. Stalemate ensued.

In 1711, the Swedish army that had defeated the Danes moved back into Pomerania to reinforce its brethren fighting Augustus's forces. This tough little army was commanded by Field marshal Count Magnus Stenbock, a wonderfully capable general worthy of the challenge.

With this war against the hated Swedes boiling away in the north, and fired-up by the honors newly bestowed upon him, Count Saxe was not one to linger long in Dresden, regardless of the hedonistic delights available at court, or the attention paid him by the women there. Thus, in the spring of 1711 he bolted for Pomerania to take command of his regiment. For the next two years he remained in the field learning much of the art of war from the Swedish adversary.

The strategy of the reconstituted Northern Alliance was to defeat Swedish mobile forces and thus knock them back into their fortified places, where they would be besieged and eventually compelled to surrender. Gradually, the allies gained ground. Maurice participated in the capture of the fortresses of Treptow and Peenemunde. Toward the end of the year Stralsund was besieged by the allies.

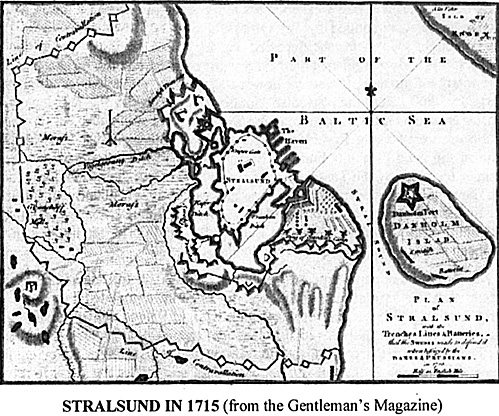

The massively built Pomeranian fortress of Stralsund was the key to victory. Stralsund was a sort of Swedish téte de pont that allowed them to maintain a foothold in mainland Europe. As long as the Swedes held Stralsund, the dream of regaining their European empire could be kept alive. Therefore, they fought with desperation to retain this point. The first siege ended in failure. The allies did not have a siege train that would allow them to batter a breach in the defenses. Hence they were compelled to launch attack after attack in an effort to take the place by storm. All these assaults were beaten back. In one of these attacks Maurice swam across the freezing river surrounding the place, losing thirty of his men in a vain attempt to carry a section of the works by amphibian means. Finally, the frustrated allies decided to lift the siege and try their luck elsewhere. In 1712 they moved into western Pomerania, all of which they eventually overran. During these operations Maurice led a successful assault on the city of Stade, hometown of the Königsmarck clan. After these successes it was back to Stralsund to try once more to take the fortress.

The investment was well underway when Field Marshal Stenbock came out of the place with 12000 men on 10 December 1712 and attacked the 24000 Danes, Poles and Saxons surrounding the place. A terrible battle ensued near Gadebusch village. On this occasion the Saxon cavalry distinguished itself. Fifteen-year-old colonel le Comte de Saxe charged three times at the head of his cuirassier regiment. A horse or two were shot out from under him, but in spite of these exertions, the Swedes gained a remarkable little victory, though in a truly pyrrhic sense. Five thousand casualties were sustained by each side, but the allies could afford such losses, the Swedes could not. Following their defeat the allies massed an overwhelming force against Stenbock, who, some months later was compelled to capitulate near the town of Toningen. Stralsund, however, remained in Swedish hands. It would not fall until 1715, when Frederick William I arrived before the place with a Prussian siege train powerful enough to breach the fortifications.

After Gadebusch, Maurice returned to Dresden on a well-deserved leave. This is also an opportune time for your narrator to take his leave until next time. In our next installment we will describe Maurice's adventures fighting the Turks in the Balkans, will be forced to deal with the dismal events comprising his idiotic marriage, and will follow his activities while fighting and debauching in the service of France.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Browning, Reed, The War of the Austrian Succession. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993

Chandler, David, Marlborough as Military Commander. New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1973

D'Auvergne, Edmund V., The Prodigious Marshal. New York: Dodd Mead & Company, 1931

Duffy, Christopher, The Fortress in the Age of Vauban and Frederick The Great, 1660–1789. London, Boston, Melbourne and Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985

Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor N., The Encyclopedia of Military History. New York and Evanston: Harper and Row, 1970

Englund, Peter, The battle of Poltava: The Birth of the Russian Empire. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1992

Nosworthy, Brent, The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1990

Saxe, Maurice, Mes Ręveries. In The Roots of Strategy, Edited by Brig. General T.R. Phillips. Harrisburg: Stackpole Books,1985

Trowbridge, W.R.H., A Beau Sabreur, Maurice de Saxe, Marshal of France. New York: Brentano's, 1910

White, Jon Manchip, Marshal of France, The Life and Times of Maurice, Comte de Saxe. Gateshead on Tyne: Northhumberland Press Limited, 1962

Map

More Marshal Saxe

- Introduction

Genes: Parents and Family

Early Days

War and Debt

Lessons Learned in Flanders

In Action Against the Swedes

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XI No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com