The outcome of events in India during the Seven Years War was very much affected by the local command of the sea where the consequences of which were more immediate and far-reaching for the belligerents. In the Indian theater, English and French forces were really "out on a limb."

Initial operations afloat involved Admiral Charles Watson and Colonel Robert Clive taking Gheria, recapturing Calcutta, Chandernagore, and the campaign on the Hooghli river leading up to Plassey. The climate proved too much for Watson's health, causing him to succumb on the 16th of August 1757. This placed Vice Admiral George Pocock in command, and, with the knowledge of French reinforcements arriving off the Caromandel coast, war had now officially broken out on yet another front, and the use of naval power would be of the utmost importance.

The first French squadron had brought 1,400 regular troops, the Lorraine regiment under the Chevalier de Loupine. 1 Pocock left the mouth of the Hooghli on the 5th of February 1758, arriving at Madras on the 23rd, with five ships of the line.

France had also dispatched a further division of ships and troops, under the Comte d'Aché. An accident in harbor and the diversion of two of his Royal ships delayed his departure. With him was the new commander-in-chief of French forces in India, Comte Lally-Tollendal. D'Aché made long work of his voyage, stopping at Rio to sell off a captured English prize. He arrived off the Caromandel coast in April 1758.

Commodore Stevens, with the English reinforcement, had sailed three months after and arrived five weeks before the Frenchman. Pocock took the newly arrived Yarmouth as his flagship, and set about looking for d'Aché, who managed to slip unseen past the English post of Fort St. David, surprising two of Pocock's frigates who had to run themselves ashore to avoid capture. 2

On the 29th April Pocock appeared to the southward. D'Aché stood out to sea, only the Zodiaque was of the French Royal Navy; the rest were converted merchant men (Indiamen). Pocock signaled for a general chase, forming line of battle within a league of the French around three o'clock. Pocock gave the signal to engage only when his own ship was within half a musket shot of the Zodiaque. 3

The Indiamen ahead of d'Aché did well, the Vengeur driving out the Salisbury from the English line. Astern, however, the Moras in turn was driven out, and the Lac de Bourgogne kept almost out of range. At 4:30 Pocock could see the rear of the French line driving up closer to the Zodiaque, so he made signals for the Cumberland, Newcastle, and Weymouth to engage more closely, but the English line was straggling. An explosion on board the Zodiaque forced d'Aché to break the French line and put before the wind, with his second astern, following, giving a fire before breaking away. Two more ships followed in like manner and the French began to veer away. Pocock hauled up the signal for general chase, but the masts, yards, sails, and rigging of the Yarmouth, Elizabeth, Tyger, and Salisbury had been shot to pieces making it impossible to follow with any speed.

With night approaching Pocock hoped to re-engage the next morning, but to no avail. Thus the two fleets drifted apart.

The French had come out the better, but one of the Indiamen, the Bien Aimé, was so damaged that she rolled on her side, coming ashore south of Alemparva. Her captain replaced d'Aprée de Mennevillette of the Duc de Bourgogne, whom d'Aché charged with cowardice.

Pocock was also forced to come down hard on three of his captains on his return to Madras. In consequence, Captain Vincent of the Weymouth was dismissed, Captain Legge of the Newcastle cashiered, and Captain Brereton of the Cumberland was to lose one year's service as a post captain.

Pocock was back at sea in May, intending to reach Fort St. David, but unable to get there, he came off Pondicherry and caught sight of the French squadron. But d'Aché was in no mood to renew the fight so soon and slipped away. Pocock, struggling to move southward, was informed on June 6th of the French capture of Fort. St. David.

Apparently d'Aché had only remained to help capture the English post with threats from Lally, and, when it came to the question of a full siege of Madras by land and sea, d'Aché refused to operate, making excuses of supply shortages and sailed for Ceylon expressing no wish to intercept trade. Lally managed to get him to return but the squabbling continued.

During this time, Pocock had refitted and sailed again on the 25th of July in quest of the Frenchman. On the 27th, just off Pondicherry, Pocock came across his opponent, but d'Aché, instead of moving toward the English line, turned to the south and kept well to the windward. Pocock gave chase in vain. Only after several days did he gain the wind and come down on d'Aché in line of battle on the 3rd of August 1758.

A brief but rather hot battle followed at about one o'clock. The leading French ship, the Comte de Province, lost her mizzenmast and was set on fire, but was covered and disengaged in time by the Duc de Bourgogne. The Zodiaque, her wheel and tiller smashed, went to leeward out of control, fire also breaking out on a deck. With the Condé and Moras both damaged, d'Aché broke off the action to return to Pondicherry. Pocock could not pursue again as he was too damaged aloft.

Indecisive as this action was, the English broadsides were used to great effect. All Royal Navy crews had acted with a better coordination than the French Indian Company sailors had. The French had lost heavily in men due to the broadsides of the English being aimed at the hulls rather than at the rigging as in the French tactics. D'Aché admitted, "the greater part of my sailors are dead or attacked with scurvy or bloody fluxes. Without sailors one can neither maneuver or fight." 4

Many of his vessels had rudder trouble or water in the hull. D'Aché announced he would have to refit at the Ile de France despite Lally's and the Pondicherry Council's insistence on his remaining, all to no avail. He sailed on the 3rd of September. Pocock retired to Trincomalee to water but was still keeping an eye out for the French, but he failed to bring on another action. So he took the opportunity provided to refit at Bombay and avoid the northwest monsoon. On his arrival there on the 25th of November, he found two men of war together with six company ships that had convoyed the remainder of the 79th Foot. Pocock saw the need for the reinforcement and supplies to get to Madras straight away and sent them off under protection of the Queensborough and Revenge on December 18th under the command of Captain Richard Kempenfelt. The small squadron slipped into the besieged town on February 16th 1759. The French commander, Lally, knew his chance to take Madras was gone and he was forced to withdraw. The English post had been saved. The lack of any blockading French fleet was decisive.

D'Aché, completely off the scene and out of touch with the situation, arrived at the Ile de France to the horror of the governor, who was unable to feed the island's population, never mind a French fleet. D'Aché found there three Royal ships under Froger de l'Equille, who had brought troops and two million in money. D'Aché kept half for his fleet and sent the remainder by frigate into Pondicherry. Conditions were desperately inadequate for refitting d'Aché's squadron, but the delay need not have been so lengthy. It was not until mid July 1759 that he once more sailed into the Indian Ocean. But the situation had changed. Without d'Aché, Lally had been forced onto the defensive at Pondicherry. The fate of the French colony now lay with the admiral.

Pocock was already cruising off Pondicherry looking for signs of the French. But it was not until September 1759 that d'Aché finally made his expected appearance. The French were spotted on the 2nd, fifteen sail to the southeast. Pocock immediately gave chase, but the wind died away and prevented his closing in, so he ordered the frigate Revenge to make sail in order to keep the French fleet in sight. On the 3rd at the break of day, the French could be seen bearing away northeast at five leagues distance. Again Pocock gave chase. He could now define eleven of the line, two frigates, and two store ships. At nine he changed signal for line of battle and hove for the center of the French squadron. But d'Aché would have nothing of it and slipped away, and with darkness approaching, he managed to lose his pursuer.

On the 4th it appeared quite apparent that the Frenchman was making for Pondicherry. Pocock would wait for the enemy to approach him by getting there first, arriving in the vicinity of the French port on the 8th of September. D'Aché sailed into view in the afternoon. Pocock persevered and on September 10th succeeded in bringing the elusive Frenchman to battle at 2:10 in the afternoon. "Both squadrons began to cannonade each other with great fury." 5 D'Aché had managed to throw two of Pocock's ships out of the action by his maneuvering. It would be eleven ships against seven.

The British van suffered a merciless pounding from Minotaur and Saint Louis, the Tyger and Newcastle only finding respite when relieved by Admiral Steeven's Grafton. The Actif, a French Royal 64 was set on fire by the Elizabeth, but the Minotaur came to her aid. The Salisbury had been hard hit by the Fortune, but a real slogging contest had developed between the flagships, the Yarmouth and Zodiaque. D'Aché being wounded, he was ushered below deck; his flag captain was killed and the next senior officer took the ship to leeward. The engagement began to break up.

Pocock's squadron was too disabled in its rigging to follow the French, who managed to reach Pondicherry with supplies on the 15th of September. As far as he was concerned, D'Aché had achieved his objective and was soon on his way back to the Ils de France. A meeting of the French council resulted in a ship being sent to catch him, charging him with the loss of the colony. With this plea he returned, unloaded more men and stores, but argued that his fleet was in no state for active operations. He sailed away; the French in India were doomed.

Indeed an English reinforcement of four ships 6 was at that moment arriving under Admiral Cornish. D'Aché sought above everything to preserve his fleet.

Pocock had received a recall back to England, and rushed through the work of repairing the fleet at Bombay before sailing. Admiral Steevens was left in command to dominate the Bay of Bengal.

On the 22nd of January 1760, Colonel Coote won an important victory at Wandewash, followed by the capturing of all French mission posts. Lally was forced back to Pondicherry, but holding this depended upon support from the French fleet. With Coote opening trenches on the landside, Steevens established a vigorous blockade from the sea, even consenting to see the siege through the approaching monsoon season.

D'Aché had not sailed for Pondicherry due to a cyclone hitting the Ile de France. Then when he was ready, a fatal order to stay and prevent a renewed attack arrived. Thus Pondicherry and her French defenders fell.

Although in the three engagements a clear-cut victory was never achieved, they had been instrumental in the fate of the three posts, Fort St. David, Madras, and French-held Pondicherry. Pocock had done enough, with his inferior number of ships, to try and bring on a decisive action, and his tenacity was aptly rewarded with his knighthood on his return home. Constant quarreling between the French commanders never helped their cause. Indeed, even before he had started, d'Aché had offered his resignation due to his poor relationship with Lally.

More Troubled Waters 1758

Corbett, J. S., England in the Seven Years War, 2 Vols.

1 Gipson.

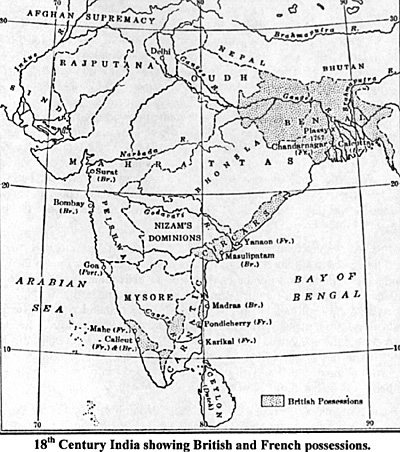

Map

Anglo-French Rivalry

Appendix I: 29 April 1758 Order of Battle

Appendix II: 3 August 1758 Order of Battle

Appendix III: 10 September 1759 Order of Battle

Sources

Derby Mercury, May 30, 1760, Pocock's Dispatch and Returns.

Dictionary of National Biography, see Pocock and Steevens.

Gentleman's Magazine, 1759, 1760.

Gipson, H. L., The Great War for Empire, Vol. 8.

Jenkins, History of the French Navy.

Sapherson & Lenton, Navy Lists form the Age of Sail, Vol. 3, Seven Years War.

Notes

2 Corbett.

3 Gipson, Gentleman's Magazine, 1759, p. 489.

4 Quote from Gipson.

5 Pocock, dispatch, 12th October 1759.

6 These ships were the Lennox (74), the captured Duc de Aquitaine (64), York (60), and the Falmouth (50). Pocock.

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XI No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com