The conclusion of the First and Second Silesian Wars had been anything but satisfactory from the standpoint of Maria Theresa of Austria. Faced with a daunting array of enemies seeking to carve up her multi-ethnic and sprawling Hapsburg dominions and fighting with an army that was not up to the caliber of that of her principal opponent, Frederick the Great of Prussia, she had been forced to accept the humiliation of ceding Silesia to the land-hungry despot so as to avert disasters elsewhere. In the interlude of peace following the Treaty of Dresden, her thoughts turned toward the eviction of her new found bÍte noir, the upstart King of Prussia, from her beloved Silesia and its eventual restoration to its proper status as a territory of the Hapsburg crown. Accordingly, resources were poured into the rebuilding of the Austrian army and plans for a future war were drafted.

The conclusion of the First and Second Silesian Wars had been anything but satisfactory from the standpoint of Maria Theresa of Austria. Faced with a daunting array of enemies seeking to carve up her multi-ethnic and sprawling Hapsburg dominions and fighting with an army that was not up to the caliber of that of her principal opponent, Frederick the Great of Prussia, she had been forced to accept the humiliation of ceding Silesia to the land-hungry despot so as to avert disasters elsewhere. In the interlude of peace following the Treaty of Dresden, her thoughts turned toward the eviction of her new found bÍte noir, the upstart King of Prussia, from her beloved Silesia and its eventual restoration to its proper status as a territory of the Hapsburg crown. Accordingly, resources were poured into the rebuilding of the Austrian army and plans for a future war were drafted.

On the diplomatic front a series of anti-Prussian alliances had been successively forged with the states of France, Russia, and Sweden.

This is referred to as the famous "reversal of alliances."

These maneuverings did not go unnoticed by Frederick, who, learning that he was to be attacked in the spring of 1757, decided to strike first. The Austrians were not quite prepared for war, but, upon learning of Frederick's preparations, they too began to mobilize.

Frederick erroneously believed that the Saxons had formed a secret alliance with the Austrians. Acting on this belief, on August 29, 1756, he crossed the Saxon border with some 60,000 men in three columns. The Saxons, outnumbered and outclassed, could only protest their neutrality and retreat to a fortified camp near the town of Pirna overlooking the west bank of the Elbe River. Here they hoped to hold out until relieved by an Austrian relief force being gathered together by Field Marshal Ulysses Maximilian von Browne, a capable general of Irish ancestry who had distinguished himself several times in the previous war.

The Saxons, less a few detached units that were able to escape, were surrounded by a Prussian observation corps while another Prussian corps of around 28,500 men under General Keith drove deep into Bohemia. This corps was intended to block any relief attempts by the Austrians as well as to gather in forage from the surrounding countryside in anticipation of the coming winter.

Browne in the interim was putting together a force and a plan designed for the eventual succor of the Saxon troops. The Saxons, with their leadership still trying to bargain for some sort of neutrality agreement with the king of Prussia, appeared disinclined for the moment to try to break out of their encirclement and march for Bohemia, a scheme that Browne had vainly espoused. Browne's new plan was to march along the west bank of the Elbe with the bulk of his army as a diversion, intending to distract Frederick from his real purpose, which was to send a flying column of some 18,000 souls across to the east side of the river whence they would force march to Pirna and extract their reluctant Saxon allies right from under the nose of their Prussian adversaries. As a strong blocking position, Browne had chosen advantageous ground in the vicinity of the town of Lobositz.

The site of the struggle is possibly the most visually striking of all the Frederician battlefields. Located on the west bank of the Elbe, the town of Lobositz itself lies to the south of a funnel-shaped plain whose northern, narrow end debauches from the last of a series of mountain ranges via a valley known as the Paschkopole. On either side this valley is dominated by two eminences; that on the western side was known as the Homolkaberg (Sugar Loaf Hill) and that on the east, the towering 572-meter high Loboschberg whose wild, steep peak was crowned with dense vegetation and whose lower slopes were crisscrossed with vineyards, stone huts, and stone fences.

Rather than attempting to "cork the funnel" by interposing his army in the upper end of the narrow valley, a position which might have been vulnerable to the enemy artillery and from which he could have been outflanked by the Prussians via his left, Browne chose to post his army in a fine position immediately behind the slow-moving Morellenbach, a small stream which had been dammed up by the locals as it wended its lazy way down to the Elbe forming a series of fish ponds, reservoirs, and morasses, all easy to defend but difficult to take. Where the slow-moving stream veered to the south, nearly in the center of the Austrian position, Fate was kind enough to place a sunken road running east and west from the Morellenbach all the way to Lobositz itself.

Browne chose to lay the bulk of his army behind the Morellenbach and deployed his avant-garde on the right in the open in a line running from before Lobositz to just north of the town of Welhotta. The rugged slopes of the Loboschberg he festooned with some 2,000 Croats whose mission was to embarrass the flank of the Prussians and interfere with their deployment. In a departure from textbook deployment practices, Browne established his right wing cavalry, including all the elite companies, in the open ground to the north of the sunken road, effectively placing them in his center.

Here they would be able to take full advantage of the only good maneuver ground to be had at this venue. He further buttressed the center by placing his heavy guns to its immediate right and deploying additional Croats at the site of the sunken road. Immediately behind the sunken road were placed the Cuirassier regiments of Stampach (CR10) and Cordua (CR14). Browne's plan was to take advantage of the Prussian doctrine of seizing the tactical initiative by drawing the Prussian army into a series of well prepared killing fields by which he hoped to take advantage of the ground and make his opponents pay dearly for every inch of ground gained. A keen eye for terrain coupled with an inspired deployment of his troops to take best advantage of the uniqueness of the ground would prove to be the saving grace of the Austrian army on this field.

Meanwhile, an anxious and irritable Frederick had become dissatisfied with the slow rate of Keith's progress into Bohemia, so he had elected to lead that column himself while retaining Keith as his second in command. Continuously harassed by parties of Hungarian light infantry, the Prussians trudged deliberately down the valley with the King at the head.

The morning air of October 1st, 1756, was heavy with a dense, impenetrable fog as the Prussians began issuing forth from the southern end of a low range of mountains known as the Mittel-Gebirge and onto the outlying plains. The foremost battalions of Keith's corps, with the King himself accompanying them, soon collided with advanced elements of Browne's deploying army, which had been hurrying up the west bank of the Elbe.

In a literal illustration of the "fog of war," Frederick, able to see very little in the obscuring mists and influenced more than a little by wishful thinking, mistakenly thought that he had contacted the Austrian rear guard, wrongly interpreting some Austrian movements and the feint and unsteady musket fire of the Croats as indications of a retreat. Frederick impetuously ordered an attack.

Frederick later characterized the view of the battlefield as if it were seen ". . . through a drape. . ." He further states: "The fog hid everything from us, and did not disperse till half past eleven." Frederick, Account of the Campaign of 1756 in Bohemia, Silesia, and Saxony by the King of Prussia, London, 1757, reprinted by Old Battlefields Press, 1998, pp. 7,8.

The Prussians advanced in three columns of infantry followed by their cavalry. Quickly seizing the Homolkaberg, about whose slopes their cavalry had already begun massing, they erected thereon a battery of five 12 pdrs, four 24 pdrs, and at least one howitzer, all under the command of Lt. Col. Moller. On the Prussian left, as three Prussian battalions entered the vineyards of the Loboschberg, they were saluted by a brisk fire from the Croats, who, happy to be in their element, made good use of the rough terrain to render themselves practically invisible to the opposing lines of infantry. The time was around 7:30 in the morning.

The main battle was joined when the Austrian batteries began bombarding the Prussian infantry as it issued forth from the valley to deploy. This fire was answered by the Prussian guns on the Homolkaberg; a bombardment which caused many casualties among the Austrian cavalry, which continuously deployed and redeployed into a variety of formations as a bid to keep the Prussian gunners off their mark. The sound of the bombardment carried all the way up the valley of the Elbe so far as to be audible to the Saxons hunkered down at Pirna.

The Austrian artillery fire was as telling as that of the Prussians, sweeping away whole files of infantry and mortally wounding generals Kleist and Quadt. On the Austrian side, General Radicati, commanding the left wing cavalry of the first line, fell dead, a Prussian cannonball assisting in the casting off of his mortal coil.

As the battle unfolded, the Austrian avant-garde on the right was reinforced by the regiments of Browne and Jung Colloredo which General Lacy had ordered up from Leitmeritz. Brown took control over the Austrian right and gave the infantry behind the Morellenbach to General Kolowrat.

As Frederick established his headquarters atop the Homolkaberg, a position which, given the fog, afforded at best an entirely mediocre view of the situation, Bevern's infantry were advanced up the Loboschberg to clear it of the Croats. An apprehensive Frederick, frustrated by his inability to discern the placement of the main body of Austrians, sent eight squadrons of cavalry consisting of the Garde du Corps, the Gens d'Armes, and two squadrons of Prinz von Preussen, all under Lt. Gen. Kyau, as a reconnaissance in force to divine their location. Kyau was hesitant and made the mistake of expressing his misgivings, which only succeeded in enraging Frederick whose judgment did not appear to be up to form on this occasion. As this force finally advanced, its right flank was enfiladed by Austrian grenadiers in Sullowitz, causing it to deviate to its left, which laid open its right flank all the more.

The second in command of the Austrian cavalry of the right, General O'Donnell, who had assumed command upon the death of Radicati, seized this moment to fall upon the exposed flank with six squadrons of the dragoon regiment of Erzherzog Joseph. Recoiling from the charge, the Prussian cavalry had to be rescued by the Bayreuth dragoons who were now thrown into the melee, driving the Austrians as far as the sunken road. Here the Croats, after first scattering to dodge the Prussian horse, proceeded to pepper them with musketry fire while the cuirassier regiments of Stampach and Cordua drove the survivors back to the base of the Homolkaberg. As the remnants of the first Prussian cavalry assault withdrew, so did the Austrian cavalry, the latter behind the shelter of their well-positioned batteries.

During the first cavalry battle, the rest of the Prussian horse had filtered through the intervening infantry units and formed up. Now these, uniting with the remnants from the first cavalry battle, renewed the charge. This was in obedience to a standing rule in the Prussian army that if the first line of cavalry failed to break the enemy line, the second line was to initiate an attack without waiting for orders to do so. A mortified Frederick watched in horror, for he did not want this second assault to occur.

To quote Frederick: "The King at that time was for placing his cavalry behind in a second line; but before this order could be brought, prompted by their natural impetuosity, and a desire for signalizing themselves, charged a second time . . ." Frederick, Ibid. p.8.

As a full fifty-nine squadrons comprising some 10,000 troopers galloped across the plain towards an uncertain destiny, Frederick could be heard shouting, "But, my God, what is my Cavalry doing, there it is attacking a second time, and who is it - who's ordering this?"

"Mais, mon Dieu, que fait ma Cavalerie, voilŗ qu'elle attaque une seconde fois, et qui est - ce qui l'ordonne?" A devout Francophile, Frederick had a greater facility in French than he had in German and often spoke French in preference to his so-called native tongue.

The charging horde quickly separated into two groups. That on the left was soon stopped by Austrian musketry and artillery fire coupled with a counterattack by three Austrian cuirassier regiments. The one on the right fared no better, becoming bogged in the marshy banks of the Morellenbach where they became easy victims of enemy musketry and cannon fire. Here Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz, of future fame at Rossbach and numerous other engagements, almost fell prisoner to the Austrians were it not for the assistance of some Prussian hussars who plucked him from the mud.

On the Prussian left the assault on the Loboschberg was not going well for the Prussians, and Bevern called for reinforcements. The Croats now had eleven battalions facing them, but, undaunted, they continued to fight with an iron will that even commanded the respect of their opponents. With ammunition running low, the Prussians adapted to the conditions of the terrain, abandoning closed formations and picking and choosing their targets using individual fire. Although a reinforcement of 120 grenadiers and 100 fusilier volunteers earmarked as reinforcements for the Austrian right unaccountably never got there, others were sent. Perceiving his left flank to be safe from any Prussian turning action, Browne placed six grenadier companies and three battalions under Lacy's command and sent them to bolster the Croats on the Loboschberg.

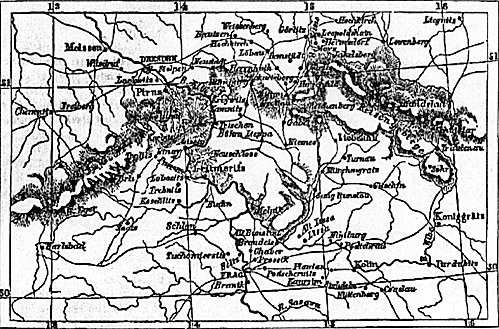

Map

Area Map of the Campaign of 1756 from Ed Allen's Horse and Musket page: http://tetrad.standford.edu/hm/FredMaps.html

More Battle of Lobositz (historical)

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XI No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com