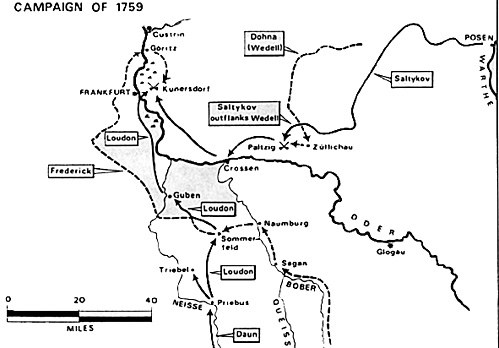

In April 1759 the Russian army, commanded by General Saltykov, arose from its winter hibernation in Poland and began the westward march towards the Oder River and the Prussian heartland. The Russian-Austrian plan for the coming campaign was simple to converge on Frederick the Great's army and hope for something good to happen. As it turned out, 1759 was to be a year of disaster for Prussia, with three great defeats at Kay, Kunersdorf and Maxen.

A Russian force of 60,000 men, including irregular Cossacks, converged on Posen in three columns. The advance guard of 10,000 reached the town on June 1st, closely followed by a first and second division, each numbering approximately 30,000 men. Frederick despatched General Dohna, whose detachment of 18,000 men was covering the Swedes near Stralsund, towards Posen. Dohna was to be reinforced by Hulsen and 10,000 men marching from Saxony. Frederick hoped that a vigorous series of actions would cut off and destroy the separate Russian columns in detail.

Dohna, however, was an old man in poor health and was not up to the task assigned to him. Frederick had long suspected that Dohna was lacking in enterprise, especially after his dismal performance at Zorndorf in 1758. Accordingly, Frederick assigned General Moritz von Wobersnow to serve as an advisor to Dohna. Christopher Duffy provides us with the following description of Wobersnow:

-

He did not enjoy a particularly high reputation in the army.

According to Warnery, 'this gentleman was old enough to have a

son who was a captain. This did not prevent him from gambling,

drinking, and whoring.

My brother, who was then a major of hussars, delivered a report to him on the eve of the battle of Kay. He found him reclining on a bale of straw with a prostitute, whom he did not even have the decency to send away'.

In 1759 the Dohna-Wobersnow combination proved to be incapable of staying the Russian advance through Poland. In July, therefore, Frederick placed them under the command of the tall, athletic and stupid Lieutenant-General Johan von Wedell, who spearheaded the advance at Leuthen.

[from The Army of Frederick the Great, by Duffy].

Wedell was an odd choice to replace Dohna, considering that he had never held an independent command, let alone commanded an entire army, and now he was assigned the task of preventing the union of the Russian and Austrian forces in the east. Frederick's orders to Wedell were to "hold the enemy up at a good position and then attack them in my style."

Wedell assumed command of the 28,000 Prussian troops assembled near the town of Zullichau on July 22, 1759. He was determined to carry out Frederick's order to attack despite the overwhelming Russian forces. Saltykov declined to attack Wedell at Zullichau, instead, he deftly maneuvered around the Prussian flank and assumed a blocking position at Paltzig, astride the Prussian line of communication across the Oder River bridge at Crossen. So now the burden of attack was on Wedell, who now needed to reopen his supply lines. Saltykov chose an excellent defensive position from which to receive the inevitable Prussian attack.

Russian Deployment

The Russian army had been deployed across a range of hills facing east toward the broad and swampy Eichmuhlen-Fliess stream. Saltykov arranged his troops in two lines of battle. The left wing stretched thin opposite a particularly impassible segment of the stream while the right wing deployed in depth behind several sandstone hillocks. Eight gun batteries were quickly situated behind field works (the first such use of this tactic by the Russians in the Seven Years War, according to Duffy) and those on the right were strategically positioned on one of the hillocks between the two Russian lines. This effective killing zone was further enhanced by the difficulties of attacking across the Eichmuhlen-Fliess stream. The only avenue of approach was up a narrow ridge leading into the teeth of the Russian defenses on the right wing.

Wedell turned his army about face and planned an attack on the Russian line across a wide frontage. His disgruntled troops were forced to throw away their afternoon meal and march west into a hot wind that blew dust into their faces. The Eichrnuhlen-Fliess forced the Prussians to advance by divisions up the ridge on the Russian right. Christopher Duffy describes the results:

-

The Russians were arrayed in two lines, with six hastily

entrenched batteries to the front, and they were able to

massacre the bluecoats as they bunched together between the

ponds and the bushes. First came the main body under

Manteuffel and Hulsen. Lieutenant von Lemcke was serving in

the regiment of Dessau during this episode, and he tried to drive

on his men, 'who refused to move from behind trees, and kept up

afire on the enemy from there. I was carrying my sword instead

of a spontoon, and I had already bent it double on my

disobedient troops when a cannon ball came bouncing along

and smnshed the sole of my left foot, throwing me to the ground

My little body of men at once took toflight. '

The Prussian second line (under Kanitz) was thrown into the battle in the late afternoon, and last of all, Wobersnow followed in the same bloody track with the rearguard. The suicidal proceedings came to an end after Wobersnow was mortally wounded by a canister shot in the side.

[The Army of Frederick the Great, New York, Atheneum, 1986, pages 186-187].

The battle lasted nearly four hours and by evening, Wedell had to retire leaving nearly 8,000 killed, wounded and mtssing on the field. Two weeks later, Saltykov hooked up with 20,000 Austrians under Loudon at Frankfurt-on-the-Oder. Saltykov and Loudon encamped on a line of hills that extended from just east of the Oder River to the town of Kunersdorf.

Frederick was now positioned between two powerful armies: the 90,000 Austro-Russian force of Loudon and Saltykov in the north and Marshal Daun's main Austrian army further south. The disasterous battle of Kunersdorf would follow on August 12, 1759; a defeat that would bring Frederick and the Prussiart state to the brink of losing the war.

Wargaming the Battle of Kay

At first glance Kay does not present itself as an interesting scenario for tabletop warfare. After all, who really enjoys attacking entrenched gun positions across a narrow front? However, Wedell's unfamiliarity with the terrain suggests an opportunity to develop what I call an invisible terrain scenario. The game judge might consider laying out the terrain with a large hill, visibly occupied by the Russians, who are facing a smaller rise in the ground between them and the Prussian starting point.

The Russian players know that the swampy Eichmuhlen-Fliess lies between the two ridges, but the Prussians are ignorant of this fact. From the Prussian point of view, they see a tantalizingly weak Russian left wing (the Prussian right) and a strongly fortified Russian right wing (the Prussian left).

Once the Prussians advance beyond the smaller ridge, the game judge can then lay out the actual terrain that lies between the two ridges. You can make life even more uncomfortable for the Prussians by informing them that only certain sections of the stream are passable to troops.

Only the judge and the Russian players know where these crossings are, or passability can be determined by a random die roll once a Prussian unit makes contact with the stream (e.g. an 'even' roll on a six-sided die allows the Prussian units to cross at that point. Once a crossing is discovered, any other units may cross there without the die roll.).

If this seems to wicked, then limit the Prussians to half movement rates across the swampy terrain. All of this serves to create a fog of war situation in which the attacker deploys in a logical manner (for example, he deploys his cavalry in what seems to be an open area suitable for cavalry melee), but as events unfold and disrupt his battle plan, it forces him to make on the spot decisions that may or may not work. I have used invisible terrain scenarios on a number of occaisions and have always found them to produce an unpredictable and exciting game.

Battle of Kay: Battle Description

Campaign of 1759. Map depicting Russian and Prussian movements leading up to the battle of Kay. Map courtesy of Christopher Duffy from Russia's Military Way to the West.

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. X No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com