Fuentes de Onoro

Light Troops in Action

by Raymond P. Cusick, UK

| |

Tn the bloody fighting for the ultimate access to Almeida that began around Fuentes de Oñoro, an incident occurred near by at Poço Velho, and those that had witnessed it were impressed at its textbook execution.

Fuentes de Oñoro - from the Portuguese side of the frontier, near the fortress town of Almeida (May 2003). Fields near the village of Fuentes de Oñoro where the Light Division who were covering 7th Division, who made their immaculate withdrawal in mobile squares when faced with the French Cavalry. Captain Ramsay’s sections of Bull’s troop RHA made their dramatic charge with sabres drawn, guns and limbers in tow, through the French Cavalry).

Jumbo Photo: Fuentes de Onoro (slow: 177K)

The manoeuvre owed its success to the basic training of the new light regiments as promulgated by Sir John Moore and to the diligence of the drill sergeants. Following the manual to the letter they drilled into the light regiments their Dundas evolutions on the parade ground at

Shorncliffe Camp and the drill fields of Brabourne Lees. [1]

As John Kincaid said, “The execution of our manoeuvre resembled a magnificent military spectacle”. [2]

The turn of the 18th century became decision time with the decision to raise permanent light infantry regiments for the British Army. The prime mover being Sir John Moore enthusiastically supported by the Commander-in- Chief, the Duke of York and a number of enlightened reformers. The decision was based on the timely and firm belief in the desperate need for such troops. Recent experiences in Flanders in 1793/4 and in the indecisive Helder campaign of 1799 had shown how battle tactics were changing. These changes were being forced by the new Revolutionary armies of France much to the consternation of the traditional ‘fire and shock’ school One who did have first hand experience to support Moore was a young Lieutenant Colonel Wesley of the 33rd Foot, (later to become the Duke of Wellingtons Regiment), who had his baptism of French fire in combat against the army of the First Republic at Boxtel in 1794.

The ignominious defeat in Flanders exposed all the current weaknesses of the Prussian system as adopted by the British Army against the new tactics employed by the Revolutionary French forces. It was here that young Wesley experienced for the first time the heavy casualties and total disruption that was caused by the new French tactic of using waves of skirmishers. The only light support available to contest the skirmishers, were the ineffectual flank battalions

[3] and a number of hired German auxiliary light regiments whose commitment was variable, such as the Hessians, who under pressure upped and fled.

But Wesley was especially impressed by a Hompesch regiment who fought on almost to the last man, with so few left the regiment was disbanded.

There were many other enlightened re-formers who supported Sir John Moore especially those who had experience in the American war where ‘La Petite Guerre’ became an art. There were also the detractors some in high places, those who considered the ‘light bobs’, the irregulars as formless bands. One British officer serving in the American

war of 1776, described light infantry as being “for the most part young insolent puppies

whose worthlessness was apparently the recommendation to serve which placed them in

the post of danger, and in a way of becoming food for powder [4] their appropriate destination next to the gallows.”

Jumbo Map: Fuentes de Onoro (very slow: 327K)

Obviously this British officer was of the

old school of powder, pomp and pipe clay.

Another detractor from the French point of

view was the émigré journalist, Mallet du Pan

who said “Tactical plans are a pure waste of

time against a vast scum of floating irregular

troops whose true force consists of their impetuous

torrent.” This was a reference to the

Revolutionaries who he said went into the

attack with waves of half trained skirmishers

in what can be called at best, random order.

One firm believer in powder, pomp and pipe clay and no supporter of light infantry was Colonel David Dundas, the Adjutant General. He was very critical of the concept and use of light infantry as it went against all the principles of Frederickian tactics of which he was a firm believer, the proof being that in the past the army of Frederick II was the most successful in Europe, employing only a token number of Jägers.

He produced in 1788, his

drill manual, “ Rules and Regulations for the

Formations, Field Exercise and Movements of

His Majesty’s Forces”, based very much on

the Frederickian tactics of the Prussian General

von Salden’s, “Elements of Tactics”. In

all the wheeling and counter wheeling the

pivot man became vital to the smoothness of

the operation, consequently Dundas had the

cognomen of ‘Old Pivot’.

Dundas considered light infantry as performing

a supporting role to the infantry of the

line, with their main function as piquets to

preserve the tranquillity of the army’. The

tactics of Frederick the Great, which Dundas

considered the only way, was to deliver a wall

of fire, massed fire from the close concentration

of muskets by platoon, division or company

and follow through with the charge with

the bayonet, the principle of fire and shock. [5]

or as Frederick has said, “those with the more

rapid rate of fire will always win.”

As critical as Dundas was, the introduction

of his ‘18 Military Movements’ did a lot

towards standardising drills at a time after

1783 and the end of the American Rebellion

when methods and discipline had become lax.

A standard drill manual was not commonly

used and drill was left very much to the fancy

of each commanding officer. Problems arose

when a brigade assembled for manoeuvres,

which could not take place until the three

commanding officers first agreed to a common

form of drill as each regiment would

have been carrying out their own version of

drill for a number of years.

In 1800, General Moore was based at his

invasion Headquarters at Ashford in Kent

forming plans for the defence of Southern

England against the threat of invasion. Moore

was also making plans for the creation of the

first light infantry regiments as an established

arm to combat the voltigeurs, who would also

act whilst in training as part of his rapid response group to thwart any French landings

and drive them off the beaches.

The new light regiments would not be

specialist marksmen as the Jägers or a corps of

Chasseurs but more like the voltigeurs, [6]

that is, a body of flexible multi-disciplined soldiers.

They were to be a battlefield tactical

force able to respond when ordered to rapid

tactical changes of plan, in other words as

multipurpose light shock troops, not to be

considered as a corps d’elite but would most

certainly be a cut above the average soldier.

Moore also rejected the idea that they should

be unformed in green as this would mark them

as a 'Jack-a-Dandy’ [7]

corps d’elite or as specialists as the 60th and the 95th.

Fuentes de Onoro Light Troops in Action

|

The Spanish-Portuguese Frontier 1811

The Spanish-Portuguese Frontier 1811

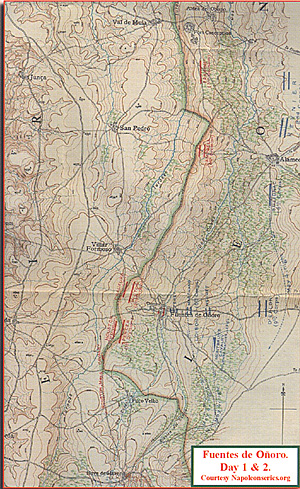

Fuentes de Oñoro. Day 1 & 2. (Courtesy Napoleonseries.org)

Fuentes de Oñoro. Day 1 & 2. (Courtesy Napoleonseries.org)