The Shadow of Ligny:

Hindsight and the Wellington-Pfuel Interview:

Tuesday 13 June 1815

The Background To The Myth

by John Hussey, UK

| |

I maintain that the grievance was unwarranted and the ‘fact’ merely convenient myth, based on hearsay. I shall present letters written in June 1815 by a future Chief of the Prussian General Staff and

shall examine his later recollections, and I shall also quote Gneisnau’s words of June 1815. Furthermore, I rely upon a German General Staff historian’s archival research conducted ninety years later. As a result I submit that one item in the catalogue of ‘charges’ against Wellington as a ‘false partner’ in this coalition campaign can be dismissed.

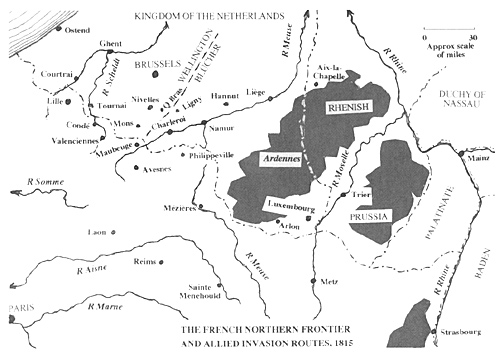

From the evening of the defeat at Ligny on Friday, 16 June 1815 there were questions asked in the Prussian camp as to what had gone wrong. A force of 83,000 Prussians and 224 guns, drawn up in a surveyed and chosen defensive position had been battered and evicted by 63,000 Frenchmen with 230 guns. 1

It was known that Wellington had met Blücher; it was said that he had promised support; it was asked why such support never came. The military ethos, building upon ordinary human predelictions,

can produce an obsessive loyalty to ‘cap badge’, the colours, the nation. When things go awry it is comforting to blame ‘that shower next door’, ‘the bloody Yanks/Poms/Poilus’, ‘les braves Belges’ or whoever 2 , to moan (as the Germans did of Austria-Hungary in 1914-18) that working in coalition is like ‘'being fettered to a corpse’ - very rare to have the honesty to admit (as did the laureate of Sheriffmuir in 1715) that there were failings on both sides.

This, it seems to me, was part of the problem for Prussian officers after Ligny: their army was no ordinary army. ‘La guerre’, Mirabeau had said, ‘est l'industrie nationale de la Prusse’ and there were explanations urgently needed if Berlin was to be satisfied. But there was something more. The greatest German historian of the campaign, Julius von Pflugk-Harttung (1848-1919), made it clear a century ago that the Prussian high command’s political agenda required that Prussia should be the main, if not sole, victor in this campaign. It provided very inadequate information to Wellington and Müffling on 15 June, leaving them with the impression that nothing major would be undertaken by the Prussians until 17 June, by which time victory would have been won; Wellington was asked merely ‘what he meant to do’.

Denied proper information, he was unwilling to commit himself prematurely; only at midnight did first news come that the Prussians had abandoned Gosselies and exposed the Charleroi-Brussels road, and by then events were moving very fast. 3

Bad Prussian staffwork which resulted in Bülow not reaching Ligny in time, together with Blücher's wasteful tactics, might have led to disaster on 16 June had Ney not been tied down at Quatre Bras by the gradual arrival of Wellington’s forces. But any thought of self-reproach for this near disaster was unacceptable. A very shaken Prussian high command needed a foreign scapegoat. Gneisnau’s report of 17 June immediately attributed blame to Wellington, 4 and though Waterloo temporarily silenced complaints the almost universal attribution of victory to the Duke's leadership did not please Prussian officers, who continued to search for traces of English perfidy. 5

Within a few years the anti-Napoleonic coalition partners had drifted apart (the 1822 Verona Congress marking the end of the old system) and by the 1830s national disagreements over Prussian and British merits in the campaign were in the military journals. The Whig government's publication in 1836 of Wellington's statements about Prussian discipline made to the Royal Commission on Military

Punishments provoked a furious reaction in Prussia and two of its senior generals - significantly, Grolman (Blücher’s QMG in 1815) and Müffling - made bitter public rejoinders which at least one sympathetic British veteran regretted as excessive.

Sir William Gomm, writing to his Prussian cousin, after lamenting the ‘injudicious and uncourteous’ publication of the Duke's words which he had been sure would bring forth ‘some expression of wounded feeling’, then continued: ‘Still General Grolman went far beyond what I expected in the shape of retort; and Müffling surprised me beyond measure, and convinced me almost that he had himself not been upon the field of Waterloo, and had never heard how the English army carried on their affairs in Spain’. 6

And 1836 is the year immediately preceding that in which ‘Colonel von Pfuel’s mission’ attained its classic status in Prussian historiography.

The Shadow of Ligny: Hindsight and the Wellington-Pfuel Interview Tuesday 13 June 1815

|

this is the story of an imagined grievance, which, arising from the frictions of coalition war and the pain of defeat, became through hindsight an historical ‘fact’, a

useful little item in the battery of accusations which were assembled during the 19th Century concerning a ‘stab in the back’ to the Prussian army in the Waterloo campaign.

this is the story of an imagined grievance, which, arising from the frictions of coalition war and the pain of defeat, became through hindsight an historical ‘fact’, a

useful little item in the battery of accusations which were assembled during the 19th Century concerning a ‘stab in the back’ to the Prussian army in the Waterloo campaign.