Napoleonic Principles of War

Review of Version II

of T.M. Pennís Rules

by David Commerford, UK

| |

A few years ago one of our club members loaned me a copy of the original rules, which I never really read and then stuck in a cupboard. Said member then left the area and the rules behind.

Yours truly, having read a bit of them, noting that they seemed to have taken over as the competition rules of choice. That army lists populated half the book and part of the rules related to setting up competitive games, decided that they must be the bastard child of the Wargames Research Group (yes, another prejudice) and left them in the cupboard. Time passed.

Our group, due to lack of opportunity to play and other factors, finally fell out with our once beloved Empire rules and drifted into General de Brigade. More time passed (we believe in a fair trial) and we decided that General de Brigade really didnít do it for us. Then while clearing out the aforementioned cupboard, what should come to light but Napoleonic Principles of War! This time they got a comprehensive read and the penny dropped. The army lists werenít just army lists but part of the rule system! Doh! A read or two later, I began to realise that there were some interesting echanisms

in the slim number of pages that actually formed the rules of play and that they could well have something worth pushing some lead around for. So thatís what we did. Quietly ignoring the small NPoW units

(three stands/12 figures for an infantry/cavalry Brigade/Regiment) we rolled out the big battalions that had started life as our Empire Brigades. Ironically we had long since ceased to use Empireís small units and these had in turn transmogrified into being the large G de B formations. We liked what we saw, continued to play with our windfall set and on release of the second version, actually parted with hard cash for copies of our own!

Now, I am notorious for my total rejection of the purpose of frontages in wargames.

Apart from both sides having the same size, that is. So it will come as no surprise that I have noticed absolutely no effect from this flagrant disregard of the authors recommendations, nor did I those of G de B for that matter.

One thing this apparent flexibility does endow you with is the ability to vary your game size. We use the big 30+ figure units (which being ex-Empire are in 9/12/15 figure sub divisions anyway) for smaller actions, splitting them up, as required, to gain more formations for the bigger ones! At the 12 figure per Brigade ratio, its not hard to see why Andy Copestake of Old Glory Miniatures told me he blames PoW, along with DBA/DBM and Shako for ruining 15mm figure sales! Though I suspect the popularity with competition gamers of the first two and the small size of armies required by them, might be a more direct link. Having said that, when you consider that the French Army at Waterloo had around 43 Infantry Brigades, including the Guard, 43x12=516 figures. Is that good or bad? Version 2 is evolution rather than revolution, building on the ideas and suggestions from players and author, gleaned since the first sets publication in 1997. At first sight there are few major changes, rather considered adjustments. However, the clearer presentation and clarifications make it a better buy than the original and a worthwhile upgrade for current owners. As I mentioned, army lists were instrumental in my ignoring NPoW the first time round but they form a key part of the rules. The reason being that they operate on a no casualty figures removal system and the lists represent not only the composition of units but the recording mechanism that takes care of strength, fire and combat ability and acts as the base figure for moral tests. All losses are recorded on these charts and the unitís

ability to fight and pass moral checks deteriorates accordingly.

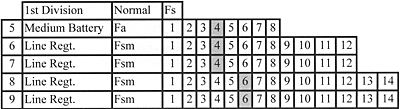

A sample is shown below. This grid is a useful way of explaining a number of features of the rules. It shows the construct for a nominal French Division. Each unit has its own ID number for tabletop

reference and is shown with a number of strength points. The shaded boxes show the starting point for each unit. Within the rules there are two options you can have fixed, or variable strength units. If you chose the later units actual values are not known until they fire, fight or check moral for the first time, at which point a die roll specific to their type, generates the actual number above this baseline,

up to the maximum available. In this way players and their opponents do not actually know if they have a good under strength unit, or a poor over strength one, or some where in between. Itís possible to have a Veteran unit with a close to base line starting strength, lower than a Conscripts generated value. However, given that the numbers of troops represented by an Infantry unit, for example, are nominally between 1000 Ė 2000 men, its possible to rationalise this situation within the number of men under arms.

Within the rules the variations between Conscripts and Veterans are dealt with in the fire, melee and moral charts. So itís still possible for a smaller Veteran unit to beat a larger Conscript one. What does happen is that using this system conscripts are not the complete waste of table space they are in some rules, which given the nature of armies from 1809 onwards is no bad thing. You will notice (Normal) and (Fs) on the top row of the grid. These refer to the Divi-sional Commanderís rating and training. In the rules all officers are rated by performance and either trained under French (Fs), Prussian or British systems. The former is an ability rating, the later governs the tactical doctrine they can employ. As you might expect the Prussian system is pretty linear, the British adds some flexibility and the French can do it all.

Some aspects of this transfer over to the actual units hence the (Fsm) notation. Included in these are skirmishing and formation types. One aspect, which some players may find controversial, is skirmishing. Being at Brigade Unit level, this activity is somewhat abstracted so as not to interfere with play. However, this does mean that in broad terms the practical use of skirmishers is confined mainly to French and British armies, with the Pre 1813 Austrians and particularly Russians, out of it. The (Fsm) in the example means that the unit is trained in the French system, can skirmish and is musket armed. The Tactical Doctrine relates not only to permitted formations on the table but also to one of the rules better features, that of built in hidden movement. At the start of action, markers represent all those units out of sight of the enemy. These, with an allowance for dummy markers, are used until such time as they either come within actual visible range, or are spotted by an opposing commander using the appropriate chart and dice roll. The control, composition and formations represented by these markers are also subject to national variation.

The hidden movement adds a nice touch to proceedings and the chart can be used, unofficially, out side this, to decide points of disagreement as to who could react to what event during the game.

To a large degree proceedings revolve around the use of initiative points (a la DBA) generated by each officer, according to a dice throw governed by his rating. These points are then expended to perform his and the units under his commandís, actions. Now I fancy you either love or hate this approach, for me itís as good away as any of creating the random effects that occur in battle and is a simple one to use. The variation of dice used per commander rating adds a bit extra. It certainly forces you to make decisions, be focused on your objective and controls players abilities to do the outrageous but if you canít stand it, these rules are not for you.

The other key aspect is the game sequence, which manages to turn the basic IGO-UGO sequence into something that feels like a continuous process. The sequence is spilt into four phases each containing a number of functions.

These are numbered 1-4 and are unusual in that the game actually starts with the first player doing those under 4, which are only for him. Then handing over to their opponent to do 1-3 and associated interactions. Following which the opponent does his own number 4 and the sequence repeats itself for the original player.

Apart from this, which takes a little getting used to, the game mechanics are simple and straightforward. Casualties, of all kinds, are on the same chart and recorded on the grids shown above. These in turn, reduce the unitís ability to fire, fight and pass moral tests. A gradual wearing down which means you have to be mindful of a unitís condition and rotate units before they brake. A good point to mention hear is that if an umpire is used to do the casualties and general bookkeeping, its very difficult for either side to know whatís going on and when units are likely to disintegrate, which makes the high

command perspective realistic. It does mean you have to produce and keep record sheets however, which some may find a pain. If you have access to a PC, Microsoft Excel and a printer, this task is really

simple once you have done it for the first time but I guess it could be irritating if you had to do it with a pen and ruler!

On that subject the other minor downside is the need for on table markers for every unit. This does mean a bit of clutter and having to ensure that they follow their parent unit all over the table but itís a price worth paying. PC owners can again easily make their own, mine were printed, cut out and stuck onto Ticket Card from the local Art Shop.

Another nice little touch is the random generation of terrain effects. A unit entering a terrain feature for the first time does not know the effect on movement until that point, having to make a dice roll to find out the hard way. The quick cross-reference chart then reveals what penalty applies and this holds good for the rest of the game. All in all the actual playing section constitutes only twenty one pages, including diagrams etc. This is part of the attraction, in that such basically simple rules produce such a good game. There are 62 ďArmy ListsĒ which are in fact for Army Corps, from all nationalities right across the 1792 Ė1815 period. Some of which are a little obscure, the Neapolitan Campaign of 1806 and Russian Army of the Caucasus, for example

There are, as in all rules, one or two things that donít quite gel. The low level of advantage for troops defending built up areas for example and one of the new sections relating to Command and Control. The latter is, as regular First Empire readers will know, a major item for me and the introduction of the concept of ďCommand AreasĒ into the new version does little to help here. Iím a real ďantiĒ when it comes to com-mand radius and to be honest this really is only the same thing given a new twist. In that the CA is determined by the distance from a marker, rather than the generals figure. Units still have

to be inside this radius to count as being in command, or suffer penalties as a result. Now this is some improvement from the norm, in that the general can wander off and do good works with his initiative points in the mean time, but really it appears to be nothing more than a device to keep formations tight and therefore historical, when dealing with small units.

If you have got this far, you might remember at the start of this review my mentioning unit sizes and frontages. Well this a theme I now return to, as I canít help but feel the CA is not a lot more than a device to stop naughty players zipping all those 12 figure units around the table in order to flank and counter flank each other, in very unreal way! Now, I could add, ďin a manner that competition wargamers are wonít to doĒ but Iíll settle for the fact that if you play with 30+ figure units, the CA seems totally superfluous during the game. On the other hand, you can play with 12 figure units and just behave! Any way, these are fairly minor moans and easily rectified in line with personal taste, another advantage of simple rules being that any player generated changes shouldnít bring the whole house crashing down! Now a pause for a shameless bit of flag waving.

The American author and rules writer, James R. Arnold once wrote that he felt that there were national character traits in wargames rules, in that American writers went for excessive detail and British ones for playability. Tom Penn has made an uncomplicated set of rules that combines playability with a good historical feel. If he turns out to be an American who just happens to live in Herefordshire, both Mr Arnold and I, are going to look very silly. Oh, one last thing, my prejudice on competition games, has it changed? Well, no.

However, I would like to say to the person who owned the 25mm Indians, in the Ancients competition at Warfare 2002, whose foremost figures, nicely painted Archers in three unbroken ranks across the table, were lined up quite literally from edge to edge. Thanks Mate! QED!

More Reviews

|

Every now and again itís a healthy thing to be confronted by ones prejudices. For me Napoleonic Principles of War did just that. Not that I have a problem with Tom Pennís rules, now out in this their second incarnation, far from it. However, it was my prejudice against competition wargames that nearly stopped me from getting into them at all.

Every now and again itís a healthy thing to be confronted by ones prejudices. For me Napoleonic Principles of War did just that. Not that I have a problem with Tom Pennís rules, now out in this their second incarnation, far from it. However, it was my prejudice against competition wargames that nearly stopped me from getting into them at all.