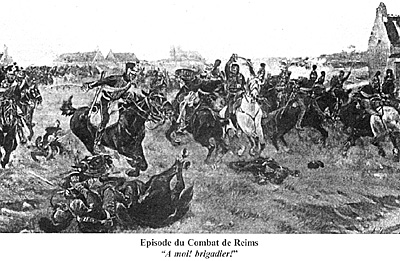

The Gardes d'Honneur and

Charge of the 3rd Regt

at Reims, 13th March 1814

The Charge of the

3rd Gardes d'Honneur

by Andrew Field

| |

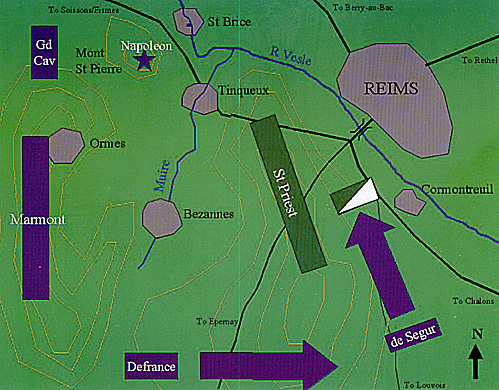

During these skirmishes the deployment of the Imperial Guard artillery eventually convinced St Priest that he was facing a significant force and it was time to withdraw. Given his position this was always going to be a tricky operation. 3,000 infantry, 12 guns and the cavalry were ordered to hold the line and cover the withdrawal. To make matters worse it was about this time that St Priest was struck by a fragment of shell and mortally wounded; his second in command, still suffering from a fall from his horse earlier in the day, declined to take over! Napoleon, seeing the activity that suggested a withdrawal, ordered Defrance to conduct a flanking manouevre around the village of Bezannes and between the roads to Epernay and Louvois to threaten this movement by cutting, or even threatening, the only withdrawal route. This move was carried out with the expectation that Bordesoulle’s I Cavalry Corps would support it. The Russian withdrawal was held up by the need to file across the Vesle bridge and into the suburbs that were protected by a wall of dirt filled barrels. As the withdrawing units became disordered approaching the defiles, the Gardes d’Honneur arrived within a thousand paces of the suburbs. The Russian cavalry on this flank, estimated at about 800 sabres, attempted to follow their move and protect the retiring artillery that was approaching the defile into the suburbs. General de Ségur was ordered to charge the Russian dragoons with the first squadron of the 3rd Gardes d’Honneur. The Russians showed signs of disorder, caused no doubt by the developing chaos behind them, so despite being only 100 strong the squadron launched a determined charge that the dragoons chose not to meet. Turning away from the onrushing Gardes they were caught in the flank and many were sabred or unhorsed. Some threw away their arms and tried to surrender whilst others attempted a desperate resistance; the remainder collided with the artillery limbers and caissons causing utter confusion. General de Ségur, who had decided to charge with this squadron, found himself surrounded by Russian dragoons and in danger of being taken or killed. Brigadier Daguerre , seeing his colonel’s plight charged to his rescue, knocking over a dragoon with the momentum of his mount. Seeing this, de Ségur shouted “à moi brigadier”, and the arrival of Daguerre and some of his comrades saved their colonel. There were many other examples of great courage in this charge: maréchal-des-logis Fresneau stood guard over the body of Count de Briançon de Vachau de Belmont, the Third Regiment’s Colonel-Major, Lt Sapinaud de Boishuguet, a Venéan, who a few days earlier had declared his reluctance to serve to de Ségur, was wounded by a ball which struck his Cross of the Legion d’Honneur, and Garde Lanneau who received eleven bayonet wounds. In a melee that lasted no more than ten minutes the dragoons were dispersed. The Gardes then turned their attention to the helpless artillery limbers and caissons backed up from the narrow entrance to the town. Brigadier Bousmann again distinguished himself; he fought his way to the lead limber, which had already made its way into the suburbs, in an effort to stop it and block the escape of those following. He reached the limber, cut down one of the crew and stopped the lead horses. However, the remaining crew struck the team and drove it over the body of the poor Brigadier, who consequently lost his prize. His injuries from this incident were so severe he was not expected to live, but de Ségur tells us that only two months later he had to be charged for missing roll call after a party! The remaining limbers were unable to escape as the Gardes cut their traces or killed their horses and it was at this stage that de Ségur looked round for the support which he was convinced would be on it’s way. A robust attack by some of the formidable cavalry force the French had concentrated for this battle would surely have been sufficient to have cut off the forward allied troops and forced them to surrender. However, despite their splendid charge, this small squadron now found themselves alone. Some shots that passed over their heads were at first believed to be from a French supporting attack. However, it soon became evident that this was Russian fire and the survivors appeared to be completely unsupported. If this were true, and we must not doubt that from de Ségur’s perspective it may have seemed that way, then it would have been contrary to all the rules for the employment of cavalry. Although the point is made in nearly all of the accounts of the battle it appears that this is because de Ségur’s narrative is the only really detailed account of this battle and is therefore drawn on heavily by other authors. However, we must remember that it is written from a very narrow perspective and coloured entirely, if understandably, from his own experiences. If we explore other accounts there is sufficient evidence to suggest that attempts were made to support him, but the difficulties of observation and the spirited fight put up by the Riazan Regiment made the attempts unsuccessful. De Ségur hints heavily that personalities also played a part; Bordesoulle in particular being implicated. It appears that Napoleon himself gave the order for the outflanking move but seems to have taken no interest in it’s results. It seems certain from studying the map that he would not have been able to see the charge and his conduct towards de Ségur later in the day suggests he was unaware of what had happened. He may have seen it as a diversion for the frontal attack on the main allied position and understandably assumed that the rest of the division was involved. Any blame therefore, seems to rest at the feet of Defrance; not because there was a lack of intent, but that the efforts were ineffective. The brigade’s second squadron did conduct a supporting charge but were thrown back as they were so weak. The actions of the 4th Regiment are not mentioned but it is hard to believe that they stood by and watched the other regiment in the brigade struggling without making any move to help. Even the actions of Picquet’s brigade are not mentioned in detail, but as we shall hear, Picquet himself was wounded and the 1st Regiment suffered heavy casualties during the battle. I suspect that the efforts of the division to support this single action, that is described in such detail by de Ségur, have gone largely unrecorded, and that de Ségur himself, having charged with the lead squadron remained unaware of what efforts were being made to support him. The shots that alerted de Ségur to the perilous situation he was in were fired by a Russian regiment withdrawing back towards the town: “Colonel Skobeleff with the Riazan Regiment, left the road coming from Tinqueux, behind the Gardes, in order to gain the Vesles Bridge, bringing back the almost inanimate body of St Priest. Ségur is taken between the fire of Skobeleff and the troops of the Bistram Regiment who garrisoned the walls, as well as receiving fire from two guns loaded with grapeshot. The Gardes d’Honneur were unable to reply effectively to this fire, suffering heavy losses which strewed the ground around the crossroads which, a few minutes earlier

had seen pass their heroic charge” . [1]

The scattered remains of the squadron were now in an almost impossible position: they were disordered from their charge, the melee and heavy losses, they were caught up in the debris of the Russian artillery and restricted by the river and a large ditch, which ran alongside the road. Feeling sure that support must be on its way and that they were in no position to carry out an orderly withdrawal, de Ségur chose to hold on

and hope for some relief. By this time he estimates that the squadron had already lost about 40 men out of the original hundred.

De Ségur was the next to fall; having been shot in the left arm he was thrown to the ground by a bayonet thrust after his horse had also been shot. He dragged himself to his feet before taking another bayonet thrust in the back, which threw him into the ditch on the side of the road. His attackers left him for dead, attracted by the rich decoration of his horse’s shabraque. This allowed him to crawl away down the ditch and take

refuge under an artillery limber.

Finding a wounded Garde, he encouraged him to follow him into the suburbs where they might find a better hiding place; finally settling into a small hut. From their refuge they listened to the Russian officers haranguing their soldiers to defend the suburbs. As night fell the Russians remained in the area of the hut which was often illuminated by the flash of their muskets. By the time it was fully dark the sounds of firing had subsided and having bound the wound of his comrade, de Ségur crept from his hiding place and immediately met a French skirmisher. Moving quickly back towards the French lines they eventually gained safety.

Rather improbably, de Ségur claims that the first bivouac they came across was that of the Emperor! Napoleon, who was anxious to get into Reims and did not notice the wounds of his ex-aide-de-camp, questioned him brusquely about the situation and then dismissed him. De Ségur then moved to the fire of the Emperor’s ADCs where having given an account of the action he finally revealed the extent of his wounds to Yvan, Napoleon’s surgeon who had tended his wounds after his charge at Sammo-Sierra. Having been moved to a mill, which served as a hospital, his wounds were properly treated and did not turn out to be serious. In the hospital he saw many of his Gardes and he was eventually returned to their bivouacs.

It was only later that Napoleon learned of his wounds and the gallant charge of the 3rd Gardes d’Honneur.

AftermathAfter dark the French finally established a bridge over the Vesle at St Brice and part of the Guard cavalry was sent across to cut off the allied withdrawal to the north where Blucher would be able to cover them. The plan to hold Reims until the next day was now abandoned by the Russians and the town was finally evacuated about 1.00am. Napoleon entered the city at 2.00am, across the ground where the charge had ended. Behind him the Gardes d’Honneur and a column of the Old Guard arrived at the defile together. As the senior regiment, the Grenadiers would normally have led, but the details of the charge seem to have spread around and the Grumblers allowed the young Gardes to go first: “for today, let them pass, they did well on this ground; they have the right to be proud and take the head of the column.” [2].

Figures given for the losses on each side are unreliable but the French accounts claim that their own losses were not more than 700 dead and twice as many wounded. There are no figures for the 3rd Gardes d’Honneur although de Ségur reckoned that at least 40 of the 100 he charged with were casualties quite early in the battle. Those of the 1st Regiment are more exact: 24 killed and 13 wounded, 36 dismounted and

only 24 remaining fit and mounted for duty. These last figures do not suggest that they sat idly by whilst the 3rd Regiment did all the fighting, as General Pully wrote to Picquet: “The losses were heavy bearing in mind how few men you had with you " [3].

Allied losses are given at around 10 guns, nearly 3,000 killed or wounded and 2,500 prisoners by French sources. It is interesting that most allied accounts are hazy when it comes to losses and those that commit themselves do not disagree substantially with the French figures.

For their action at Reims seven Crosses of the Legion d’Honneur were awarded to the Division of Gardes d’Honneur (although de Segur claims he secured 20 for the 3rd Regiment alone as well as 19 commissions!). In his 14th Bulletin, dated 16 March, Napoleon wrote: “General Defrance made a superb charge with the Gardes d’Honneur, who covered themselves in glory, particularly General Count de Ségur, commanding the 3rd Regiment, who charged between the town and the enemy, whom they drove into the suburbs, and from whom they took

1,000 cavalry and his artillery…The 10th Regiment of Hussars, as well as the 3rd Regiment of Gardes d’Honneur, particularly distinguished itself. General Count de Ségur has been severely wounded, but his life is not in danger.”

Napoleon’s victory at Reims was insignificant in the broader context of this campaign, but was remarkable none-the-less after the costly engagements at Craonne and Laon. Its effects were short lived but vital to Napoleon at the time: ‘the last smile of fortune’ as Marmont described it in his memoirs.

After a short rest at Reims, Napoleon then moved south to tackle Schwarzenberg. Defrance’s division was used to scout ahead of the army and was involved in numerous skirmishes with Cossacks. However, they took no part in the battle at Arcis-sur-Aube, watching the eastern flank of the army during this engagement. They again scouted ahead as Napoleon attempted to lead the allied armies away from Paris by moving

on their communications, but this marked the end of their actions in this campaign: having marched on Paris rather than follow Napoleon, the allies fought the last major battle of the campaign under it’s walls in the absence of the Emperor. His final gamble having failed, Napoleon returned towards Paris only to abdicate once he realised the situation was hopeless.

By the end of the campaign the division of Gardes d’Honneur numbered only 553 men present, including the 10th Hussars. The 1st Regiment was reduced to only 40 men. These regiments had a rather short and inglorious existence, but is a shame that they tend to be remembered for their indiscipline and desertion rather than their creditable performances and courage at Leipzig, Hanau, Montmirail and Reims.

[1]. Lt Col Fleury: Reims en1814, pendant l’invasion .

Quoted in Lomier.

Lomier, Doctor. Histoire des Régiments de Gardes d’Honneur.

More Gardes d'Honneur

|