The Netherlands Victory

Quatre Bras 1815

French Attack at Charleroi

by Peter Hofschröer, Germany

| |

The French assault on the Prussian outposts around Charleroi commenced at dawn on 15 June. By late morning, Charleroi had fallen to Napoleon’s advancing troops. His scouts then pushed on towards Quatre Bras. The local allied commander, Major-General Duke Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, assembled his troops, Nassauers of the 2nd Brigade of the 2nd Netherlands Division, to meet the French.

He addressed his battalion commanders saying, ‘Gentlemen, I have been given no orders whatsoever, but I have never heard of a campaign beginning with a retreat, so let us make a stand at Quatre Bras’. [7]

His men were concentrated by 7 PM, the first French scouts arriving about the same time. Sporadic fighting went on until nightfall. At 9 PM, Saxe-Weimar reported the situation to divisional headquarters in Nivelles, pointing out that he was low on ammunition. Captain Gagern was then sent to corps headquarters in Braine-le-Comte. In the absence of the corps commander, the Prince of Orange, who was in Brussels, Major-General Jean Victor de Constant Rebecque, his chief-of-staff, ordered Quatre Bras to be held. At 10.30 PM, Constant Rebecque sent Lt. Webster of the 9th Light Dragoons to Brussels with an urgent message. Webster arrived about midnight. On receipt of the news, Wellington packed off the Prince of Orange back to his headquarters, telling him he was moving a substantial part of his army to Quatre Bras. [8]

However, that was not the case as an officer of Picton’s 5th Division, which was stationed in Brussels and due to be the first to march south to the front the next morning, noted that, ‘Whatever these despatches contained, the arrival of which would soon be whispered about the room, and create a sensation, no farther change was made in the chief’s arrangements as concerned us, than altering the hour of departure in the morning from four to two o’clock’.

[9]

Despite the arrival of the news of the French breakthrough to Quatre Bras about midnight, Picton was still not ordered there. Orders sent to other troops in the Brussels area confirm this. Captain von Sichart’s report on the role of the Brunswick contingent mentions, …The Duke [of Brunswick] received an order

from the Duke of Wellington to pass through Brussels with his Corps, to march to Waterloo on the Charleroi Road and to await further orders there,

[10]

South of Waterloo, there was a fork in the road. One road led to Quatre Bras and towards Blücher’s positions, the other to Nivelles, from where a French advance via Mons could be countered. Wellington had yet to decide in which direction to move. At 7 AM on 16 June, just before leaving Brussels to ride to the front, Wellington issued a further set of orders. However, none of these was to his Reserve, and none was for any troops to move on Quatre Bras.

There are several accounts of Wellington’s fear that the main French thrust would come via Mons, the shortest route to Brussels. Wellington had left his options open to deal with that. Wellington left Brussels, riding south down the road towards Nivelles and Namur. About 9 AM, he came across his Reserve resting at the Forest of Soignes, having its breakfast. He left those troops there and rode on, first stopping at the road junction at Waterloo. Here, he sought confirmation of where each of the forks led. The Duke had yet to decide down which fork he was going to send his Reserve. About this time, it would seem that the Brunswickers were ordered to Genappe.[11]

Here, they could hold the narrow bridge against a possible French advance, preventing any movement by the Reserve to Nivelles being interrupted. Wellington then continued his ride to Quatre Bras, where he arrived about 10 AM and inspected the position. At 10.30 AM, he wrote Blücher a letter in which he indicated, misleadingly, that his army would be able to support the Prussians at Ligny that day. As the 5th Division received its orders to march to Quatre Bras between noon and 1 PM, and as it was resting about one hour’s ride from Quatre Bras, Wellington must have ordered it to that point between 11 AM and noon. He did not order any other

troops to Quatre Bras at that time. Logically, Wellington had no reason to do so. As we know, he feared the main French thrust would come via Mons.

Moreover, he was aware the Prussians had engaged only part of the French army. About midday, the sporadic skirmishing ceased and there were no signs of French movement, so Wellington did not order any more troops there. The remainder of his army was moving into positions where it could deal with any French move via Mons, so what else did Wellington need to do at this time?

Having secured his line of communication with the Prussians, Wellington left Quatre Bras about midday and rode to Blücher’s headquarters at the windmill of Brye, near Ligny. Here, the Duke saw a substantial part of the French army drawing up to attack the Prussian positions. The remainder of Napoleon’s ‘Armée du Nord’ had still to be accounted for. As it was not visible at Quatre Bras, then this probably reinforced the Duke’s suspicion that it was moving via Mons. Only when he returned from Brye did his error of judgement become apparent, for, in his absence, Ney had drawn up his forces and begun to assault the Allied positions at Quatre Bras.

More Netherlands Victory Quatre Bras 1815

Related

Quatre Bras 16th June 1815 [FE59]

|

At right: Trooper, 6th Dutch Hussars 1815 © Osprey Publishing.

At right: Trooper, 6th Dutch Hussars 1815 © Osprey Publishing.

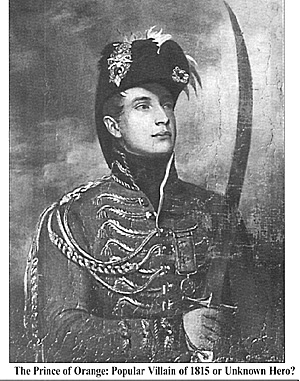

At right: The Prince of Orange: Popular Villain of 1815 or Unknown Hero?

At right: The Prince of Orange: Popular Villain of 1815 or Unknown Hero?