More on 'Plunket's Shot'

'Retreat to Corunna'

by Richard 'Rifleman' Rutherford-Moore, UK

| |

I'd like to offer a little more 'food for thought' for readers after my previous article (FE49) in which I reviewed the traditional background and the circumstances of "Plunket's Shot". The illustration by Harold Payne of Tom Plunket shooting Colbert, from The Rifle Brigade Chronicle of 1914. Harry Payne's complete sketch shows British earthworks' as referred to by the French in their account. When, in late July 1808, the 1st Battalion 95th Rifles left Dover for the Peninsula, as previously stated Plunket already had the reputation for being 'a crack shot' after his exploits in South America, and further enhanced his appreciated ability to contribute to morale and be the 'life and soul of the party' by performing, throughout the voyage, The Hornpipe and the 'double-shuffle' (probably an Irish Jig) to the applause of all present. He was already held up by his company commanders to be the 'exemplary soldier' Sidney Beckwith later confirmed, and no doubt this had an effect on the younger or newly joined riflemen. The 'old road' as used by the troops didn't pass through nearby Pontferada so that village didn't suffer the usual privations at the hands of the British soldiers during the retreat, but the French did use it as a resting-place on the night of January 2nd (and according to the town history as outlined to me recently they didn't - unlike the British - 'tear it apart).

Due to modern infrastructure, battlefield explorers now have the 'old road', the 'new old road', the 'old new road' and the 'new new road' to contend with in the area, all of which are indifferently, signposted in places and run almost parallel with each other. Pilgrims to Santiago de Compostela in the area always follow the scallop-shell motif and use the 'old French road' should you ever get lost there. Parts of the actual road used by Sir John Moore's army still exist in many places from Astorga to Betanzos but are sometimes a little inaccessible, quite circuitous, can be treacherous underfoot, steep and even unexpectedly even disappear! Legend and Tradition "Plunket's Shot" is shrouded by legend and 'tradition' through the varying accounts of it. A rifleman -who wasn't present at the time but heard about it second-hand from someone who was - later suggested in his memoirs that Colbert was such an efficient nuisance chasing the British rearguard that Paget pointed Colbert out to the soldiers of the 95th Rifles and offered a financial reward to anyone that could shoot him dead, an unspoken offer that Tom Plunket obviously decided to take up. Sir Edward Paget is said to have tossed Plunket his purse or some coins from it when he later heard about the exploit; however it is said that it is doubtful if Sir Edward Paget would have ever encouraged personal action such as Plunket's in such a fashion. Paget is also said to have afterwards commended Plunket to Sidney Beckwith, the 95th'S commanding officer. It did start a rumour in the ranks of the French that British officers paid their men in cash to shoot French officers in battle. The History of the Rifle Brigade states that it is unlikely that Edward Paget would ever have offered a private soldier money to 'slay a brave and chivalrous enemy guilty only of doing his duty' but he may have flung his purse or some of the contents to Rifleman Plunket 'in admiration of two unerring shots taken in the heal of battle'. Later on in the war, enemy soldiers certainly were pointed out to British riflemen by their officers as targets in battle, but no accounts say anything of a financial reward being offered at the same time, nor given later in the case of success. The rifle officers prime concern in battle seem to be that their riflemen would close the range on the enemy, thereby taking unnecessary casualties. To 'shoot a Frenchman for yourself became a proverb in the 95th Rifles linked with the rather dubious personal claim by the rifleman concerned on the enemy's dead body for plundering purposes later. Good shooting 'at the Horse' in practice back at Barracks did sometimes earned a new Rifles recruit sixpence from a watching Officer, given as an encouragement. A minority of Rifles officers on active service in the Iberian Peninsula began to acquire Baker rifles themselves after early 1813, although it isn't clear for what purpose; surviving examples indicate a 'sporting' specification (i.e. omission of the sword-bar, with engraving on the brass furniture and 'chequering' on the wooden stock) but they would obviously be as effective as the military specification if ever used in battle.

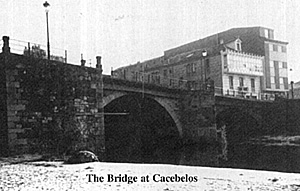

Reports and observations about the Riflemen of the pickets running back towards Cacabelos 'with some difficulty' were probably the basis for the statement they were 'drunk'. The pickets of the 95th were soldiers that had already performed well on a cruel march at some speed of some duration over a ice-bound and hard country road and had been out for a long period the previous night and most of the morning in the freezing conditions; I don't mind admitting that under these conditions I'd only be capable of running 'with difficulty'. In the same conditions, if there were any alcohol around I'd have drunk it too; the effect of spirits on a soldiers' empty stomach is already well recorded by soldiers on the 'Retreat to Corunna'. Confusion The confusion at the bridge at Cacabelos during the early part of the action might have put more men than Plunket in a bad temper. Sir John Colbourne (on Moore's staff serving as Military Secretary at the time) left an account of this part of the action. Colbourne says he found Sir John Moore 'in a great fuss' because of Colbert's first charge, as Moore never 'thought they (the French) were so near!' Moore was criticised later by Sir Arthur Wellesley through not co-ordinating his planned halts for the troops on the road with more efficiency in view of the close proximity of the French pursuit. The staff obviously responsible for this were equally as exhausted and harassed as everyone else, and the Retreat overall was conducted at a speed greater than that usually arranged for transit marches in fine weather on good roads in England, but with far worse communications and administration. The rearguard probably couldn't leave Cacabelos before the soldiers of Hope and Fraser were leaving Villafranca. Apparently no plans were ever made to blow up the bridge at Cacabelos, that would have had to wait until the rearguard had crossed, but with hindsight there seems to have been the time for engineers to prepare it for demolition had there been any engineers present and any orders given to them. The engineers had previously successfully blown three arches out at Castro Gonzalo bridge near Benevente despite pouring rain, but failed in their next two attempts at bridges along the road (Constantino and Betanzos) much to the annoyance of General Paget (1).

Their later effort at Burgo bridge was extremely successful. Whether - due to the nearby useable ford, in all accounts useable on the day - blowing up the bridge would have seriously impeded the French pursuit at Cacabelos is doubtful. The French account seems to indicate that in the opinion of the 'man on the spot' the river was fordable by infantry upstream in addition to downstream.

The range that Plunket fired over isn't clearly defined. The village of Cacabelos has changed so these days any detailed exploration and examination of it leaves you with a potential range of anywhere between a possible 100 and a rather unlikely 600 metres after taking into account the various descriptions of what may have happened. Various factors can be taken into consideration during these speculations - the spot where the French cavalry reformed, the range of the guns of the British horse artillery, the space and time covered by a charging trooper allowing Plunket to run back the hundred yards to safety, the time taken to reload a Baker rifle then take aim and fire, the angle of the road and the elevation of the bridge, the difficulty of the shot in the freezing weather by a man who was already tired and now possibly breathless - etc. In one account Plunket leaps over the bridge parapet after firing his second shot, narrowly escaping the vengeful French by a drop of thirty feet into a freezing cold River Cua!

In one account Rifleman Plunket whilst 'lying on his back in the snow' shoots General Colbert 'at a range of 400 yards.' The road through the village to the bridge at Cacabelos still takes roughly the same route as in 1809, but building beyond the nearby Plaza Mayor has expanded greatly since then. The 'eastern' ridge, the Plaza mayor, the bridge itself, the church, the old mill and the gardens and vineyards which feature in accounts of the action can still be found. Two possible positions for the British horse artillery can be debated (using my parameter of 600 yards as maximum effective range) between two to three hundred yards from the riverbank. The ford used by the French has however largely disappeared, but a spot a hundred and fifty or so yards downstream from the bridge could be the place. In his book, Captain Gordon of the 15th Hussars left us a sketch of Cacabelos village and its environs with troop dispositions at the time of the initial fighting there on the day, and is a good map to begin with. Only Time limits any explorations here - but watch out for ubiquitous (and barking-mad) Spanish dogs!

After his death, Colbert's cavalrymen 'traditionally' charged over his body towards the bridge. In one account, Colbert's horse was seen faithfully standing next to his dead body in the roadway towards the end of the fighting. In another account, it is the Trumpet - Major of one of the French cavalry regiments that is killed by Plunket's second shot; another account states it was Colbert's aide de camp (Lieutenant de la Tour Maubourg) and the shooting didn't happen until Colbert's men had actually crossed the bridge.

A French source names Colbert as 'the legendary General of Brigade Baron Auguste de Colbert de Chabanais' and says he fell during the second advance after seeing his aide shot and after passing French skirmishers on the eastern bank from a shot from the British 'entrenchments' which struck him just above the left eyebrow and passed right through his head, killing him instantly and throwing his body back from his horse. If this French account is taken to be correct, the shot, which killed Colbert, was probably fired at a range between 50 and 75 metres. A fellow shooter added that at this range he would expect the bullet from Plunket's rifle to have the described effect. Oddly enough, the sketch of Plunket included as an illustration in the previous article does show British ' entrenchments' in the original form. No British account mentions any 'digging-in'.

The last entry in Sir John Moore's diary closed in his headquarters on the Canton Grande in Corunna reads 'I cannot imagine after what has happened there can be any intention of sending a British force again into Spain." As a Spanish proverb says, "Revenge Is A Dish Best Eaten Cold. " The story of "Plunket's Shot' probably did grow large from what happened on January 3rd 1809 during the telling of it (2) but the personal exploit itself of a single soldier at a very dark and dismal time and the powerful contribution it made in this fight during the terrible retreat to the morale of the entire rearguard - and to efforts of British riflemen fighting the French in the following years of the Peninsular War to emulate it - was probably immense. British officers recalled that the battle at Cacabelos renewed the 'will to fight' in the ranks of the hard-pressed Reserve; the rise in morale the Reserve gained through this little victory did help them along over the next sixty miles through the lofty and snowbound Sierra Cebreiro mountains before the long march still to come after them, to Corunna.

Whatever happened, in my opinion 'Plunket's Shot' is now immortal no account of the 'Retreat To Corunna' is complete without it, and I never omit a chance to tell it in all its Glory.

(1). "What, Sir! Another abortion? And Pray how do you account for this?" General Paget to an Engineer officer after a failure to blow up a bridge on the Retreat to Corunna; as brilliantly recalled by Rifleman Harris.

With acknowledgements to the works consulted in this and the original article 'Adventures of a Soldier' Edward Costello

|

Private John Warwick of The Berkshire Volunteers in 1872 shooting a military rifle in competition, still employing the 'supine position' for accuracy. Warwick was accounted the 'finest rifle shot in England' at the time. "Plunket's Shot!" was one of the many traditional 'after-dinner toasts' at contemporary 'Rifle Volunteer' targetshooting events.

Private John Warwick of The Berkshire Volunteers in 1872 shooting a military rifle in competition, still employing the 'supine position' for accuracy. Warwick was accounted the 'finest rifle shot in England' at the time. "Plunket's Shot!" was one of the many traditional 'after-dinner toasts' at contemporary 'Rifle Volunteer' targetshooting events.

A robust Baker rifle, circa 1803 .1 musket-bore rifles were dropped before this time as being too bulky and heavy and the calibre of twenty-bore (that of the cavalry carbines and pistols) and a more graceful design of Baker rifle followed from 1802. The rifle lock is quite plain; this is the form of Baker rifle Tom Plunket would have been originally issued with, capable in the hands of a reasonable rifleman of placing balls within an 18 inch grouping at 100 yards, firing offhand.

A robust Baker rifle, circa 1803 .1 musket-bore rifles were dropped before this time as being too bulky and heavy and the calibre of twenty-bore (that of the cavalry carbines and pistols) and a more graceful design of Baker rifle followed from 1802. The rifle lock is quite plain; this is the form of Baker rifle Tom Plunket would have been originally issued with, capable in the hands of a reasonable rifleman of placing balls within an 18 inch grouping at 100 yards, firing offhand.

A equally robust target rifle, calibre twenty bore made by William Moore or James Fenton, circa 1810; Ezekiel Baker after 1806 introduced as standard onto military Baker rifles all the lock innovations seen here (sliding safety catch, ring neck cock, raised semi-waterproof pan, and possibly the roller on the frizzen spring, etc) but the rifling in the Baker always remained the same. The tighter rifling in this arm would enable a rifleman of reasonable experience to place balls on target within the same 18-inch grouping but at 200 yards, offhand. Advanced sights when fitted made this form of arm accurate at longer distances. However, reloading with the enhanced rifling of this arm would have necessitated far greater care and time on the part of the user. Suggestions privately made to The Board of Ordnance after 1808 that Riflemen of the 95th should be equipped with this sort of arm in proportion or replacing the former were never really considered.

A equally robust target rifle, calibre twenty bore made by William Moore or James Fenton, circa 1810; Ezekiel Baker after 1806 introduced as standard onto military Baker rifles all the lock innovations seen here (sliding safety catch, ring neck cock, raised semi-waterproof pan, and possibly the roller on the frizzen spring, etc) but the rifling in the Baker always remained the same. The tighter rifling in this arm would enable a rifleman of reasonable experience to place balls on target within the same 18-inch grouping but at 200 yards, offhand. Advanced sights when fitted made this form of arm accurate at longer distances. However, reloading with the enhanced rifling of this arm would have necessitated far greater care and time on the part of the user. Suggestions privately made to The Board of Ordnance after 1808 that Riflemen of the 95th should be equipped with this sort of arm in proportion or replacing the former were never really considered.

The bridge over the river at Cacabelos today. The River Cua at the spot is both deeper and narrower today because of a mill-weir. A plaque was placed here by The Royal Green Jackets of the modern British Army recreating the 'Retreat To Corunna' march in 1985 - reportedly since disappeared.

The bridge over the river at Cacabelos today. The River Cua at the spot is both deeper and narrower today because of a mill-weir. A plaque was placed here by The Royal Green Jackets of the modern British Army recreating the 'Retreat To Corunna' march in 1985 - reportedly since disappeared.