Plunket's Shot

'Retreat to Corunna'

January 2 – 3, 1809

A personal view of one part of the actions at Cacabelos

by Richard 'Rifleman' Rutherford-Moore, UK

| |

Tom Plunket was a popular character. One of his comrades describes him as 'a smart, well-made fellow, about the middle height, in the prime of manhood; with a clear grey eye and handsome countenance – a general favourite with both officers and men, besides being the best shot in the Regiment.' He was noted for being the 'life and soul of the party' at all times, a good companion and a entertaining dancer. Another rifleman – an officer – says of him . . .'Plunket . . . was a bold, active, athletic Irishman and a deadly shot; but the curse of his country was upon him.' The 'curse' of habitual drunkenness saw Plunket's several promotions lead to his reduction each time back to the ranks. Tom's reputation as an 'excellent shot' emanated from his inclusion in the force sent under Lt.-Gen. John Whitelocke to capture Buenos Ayres in 1807. Although a military disaster, Plunket was seen to have spotted and shot a Spanish officer at long range, receiving the plaudits of his company for doing so. In March 1809, the Rifles left Dover for the Peninsula. After the early victories, the 1st Battalion 95th Rifles ended up in the rearguard of the army then marching at top-speed for Corunna through the Spanish Sierras in wintertime. From Astorga onwards, they were hard-pressed by the enemy cavalry, performing wonders trying to pin down or cut off part of this rearguard for the French infantry behind them to finish. Sir John Moore, then commanding the British Army, had witnessed on January 2 a particularly disagreeable episode where his retreating soldiers had ransacked Villafranca and turned it into a wreck in a drunken riot. As the artillery smashed up their carriages and threw the ammunition into the river, a dirty pall of smoke hung over the town, echoing with pistol shots as the emaciated horses were shot. In the town, all the stores had been looted, houses and shops plundered, civilians killed, churches used as barracks, the streets filled with upturned casks of ships' biscuit and rum, broken baggage carts, with clothing and blankets strewn everywhere. Moore watched a soldier shot for striking an officer in the Plaza Mayor then rode back east to see how the rearguard were progressing before Cacabelos. Moore made a speech to the rearguard in a 'feeling and pungent' manner described by one of the officers present as 'formidable and pathetic' [1]; that night in response they ransacked the village houses in Cacabelos looking for drink.

As the floggings went on, the French were reported several times to be in motion. Paget received each report with a solemn nod, and a simple 'Very Well'. Finally, after several hours had passed, all that needed to be done was to hang two soldiers caught thieving. As Paget watched the two men being made ready, the sound of gunfire came over the hill in front. General John Slade, one of the cavalry Brigadiers galloped up and reported that his troopers were under pressure and retiring. Paget already had a low opinion of Slade; he replied to Slade's report in a loud voice "I am sorry for it. But this information is of a nature that would induce me to expect a report from a private dragoon rather than you. You had better go back to your fighting picquets sir and animate your men to a full discharge of their duty."

As Slade rode off, Paget fell silent. The hangmen were watching him for the signal to 'turn the men off' and execute them. Paget was seen by one officer to be 'suffering under a great excitement' and finally looked up and bellowed out "My God! Is it not lamentable to think that instead of preparing the troops confided to my command to receive the enemies of my country I am preparing to hang two robbers ? BUT – even though that angle of the square be attacked, I shall execute these villains in the other! "

A strange silence, dotted only by the odd rifle and carbine shot from the distant hill, fell over the troops for two minutes. Paget spoke again. "If I spare the lives of these two men, will you promise to reform ?"

The silence continued, during which Paget repeated his offer. Several officers nudged and prodded their men into saying 'Yes' until finally it was shouted across the square. Paget ordered the soldiers to fall out and make ready for battle just as the French cavalry rode over the top of the hill behind them.

A remarkably good-looking and well-dressed French General named Auguste-Marie-Francois Colbert - possibly taking over from the unlucky Lefevbre-Desnouettes at Benevente [2] - was seen at various times by the Rifles for his activity and daring in leading their cavalry, conspicuously riding a grey horse at the front but seemingly proof against every attempt the riflemen of the 95th Rifles made to shoot him off it. Colbert commanded 450 to 500 troopers of the 15eme Chasseurs a Cheval and the 3eme Hussards; having now caught the British rearguard he meant to damage or destroy them before they could move off. He swept down the hill chasing the vedettes of the 15th Hussars and the pickets of the 95th Rifles (many of whom were seen to be running with difficulty, possibly drunk)

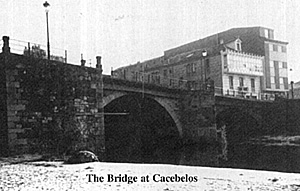

Paget had ordered the rearguard to cross the river by the bridge. The Light Company of the 28th Foot had been drawn up on the 'eastern' side to cover the crossing of the horse artillery. Whilst units were still crossing, the hussars and riflemen appeared with the French hot on their heels; the bridge and its approaches were quickly blocked with cursing, swearing infantry and troopers from both sides. In the confusion, several of the 15th Hussars were overwhelmed and fell bravely fighting the French, who then began to round up fifty drunken or exhausted riflemen of the 95th that hadn't been quick enough down the hill. Colbert saw his troopers becoming disorganised and getting dispersed, and with the bridge now completely jammed with greenjackets and redcoats, finally ordered their recall to try and reform to take advantage of the fact that half the British rearguard were still on the 'eastern' side of the river.

As Sir John Moore and his staff [3] tried to sort out this confusion, Slade rode up to Moore and asked if he could make a report given to him by Colonel Grant, one of the officers in his command, who had asked him to do so. Moore then rather sarcastically asked General Slade how long he'd been serving as Colonel Grant's aide-de-camp.

The 52nd Foot had not crossed the bridge; they were still drawn up in line at the base of the hill on the 'eastern' side. The 95th Rifles had been 'herded' into the houses and over the garden and vineyard walls on either side of the bridge on both banks. The six guns of the horse artillery battery was quickly sent up the hill on the 'western' side and the Light Company of the 28th Foot drawn up beneath it on the lower slopes, supported at a little distance by the rest of the battalion.

Colbert reformed his cavalry, obviously preparing for another attempt. As the squadrons began to advance at a fast trot, the horse artillery of the rearguard opened fire, sending shot bouncing up the road and over the frozen fields towards them. Colbert was obviously going for the bridge this time; but the charge in preparation was seen by one British officer to be 'most ill-advised, ill-judged, and seemingly without any final object in view'.

Plunket was on the western side of the river with his company of the 95th Rifles. Seeing the French reforming, and Colbert conspicuous as usual in front, he ran forward about a hundred yards and threw himself down on his back on the bridge itself. Adopting the 'orthodox position', he placed the butt of his rifle in the pit of his right arm, looped a foot through the sling and took careful aim. As Colbert turned and ordered the charge at the front of his men, Plunket fired. As the smoke from his shot cleared, Colbert was seen to fall from his horse, the bullet having struck him in the forehead. Plunket leapt up and began to reload his rifle.

Another Frenchman rode up to Colbert's body, dismounted and looked down at him; Plunket then shot him too. The furious French troopers then galloped down the slopes toward Plunket on the bridge, who swiftly ran back to rejoin his cheering comrades with a dozen Frenchmen close behind.

The French cavalry came under a heavy fire from the 52nd Foot and the 95th at the bridge, before some brave troopers actually crossed the bridge despite the hail of shot from the horse artillery and for a time fought sabre to bayonet with the Light Company of the 28th Foot. They were however after a short time forced to withdraw, passing once again through the deadly crossfire from the redcoats and greenjackets and leaving many men and horses dead on both banks and on the bridge itself. One British officer saw a dead Frenchman with a foot caught in a stirrup dragged by his terrified horse through the mud to the river, his head bouncing and banging up and down on the frozen surface; this single and terrible remembrance stayed with the young officer for years after the war was over and he had forgotten almost everything else.

French infantry were now moving up. Little over an hour later, the French tried again to cross the River Coa, this time by a ford downstream from the bridge. As the French skirmishers followed their cavalry, the 95th were sent down towards them supported by the 52nd Foot. More French infantry came in column towards the spot vacated by the 52nd; as they reached the river they were blasted at close-range by the six waiting guns of the horse artillery and broke. The French cavalry and infantry at the ford fared no better – after a brief fight they too turned and withdrew, hotly pursued by the now invigorated 95th and 52nd. The firing died away with the onset of night, and the still cheerful rearguard left for ruined Villafranca, leaving the French to mop their bloody nose and lick their wounds. Both sides had lost over 200 men killed or wounded in the fighting.

'Plunket's Shot' is surrounded by legend and tradition. A rifleman who was there stated later that Colbert was such a nuisance that Paget pointed Colbert out to the 95th and offered a financial reward to anyone that could shoot him; an offer Plunket decided to take up. Sir Edward Paget did toss Plunket some money or his purse after he heard about the exploit; however it is doubtful if Paget – a brave, chivalrous if rather fierce officer – would order such an act. Paget is also supposed to have afterwards commended Plunket to Beckwith, the 95th's commanding officer. It did begin a rumour in the ranks of the French that British officers paid their men in cash to shoot French officers in battle.

The range that Plunket fired over is disputed. The village of Cacabelos has changed so much these days that any exploration and examination leaves you with a range possibility of anywhere between 200 and 600 metres [4].

Various factors can be taken into consideration during these speculations – the spot where the French cavalry reformed, the space and time covered by a charging trooper allowing Plunket to run back the hundred yards to safety, the time taken to reload a Baker rifle and take aim and fire, the angle of the road and the elevation of the bridge, the difficulty of the shot in the freezing weather by a man who was already tired and now breathless.

Colbert's cavalrymen traditionally charged over his body towards the bridge. In one account, his horse was seen faithfully standing next to his body in the roadway towards the end of the fighting. In another account, it is the Trumpet-Major of one of the French cavalry regiments that is killed by Plunket's second shot.

Colbert was a skilled soldier of note; he knew the French infantry were close behind him and also Bonaparte's wish for 'more English mothers to feel the horrors of war'. The French later said they would 'rather fight a hundred fresh Germans than ten starving Englishmen' [5]. At the time, the risk was probably judged by Colbert worth taking; he certainly led from the front in that belief.

Tom Plunket was observed by several men during the ensuing battle at Corunna taking certain and deadly aim at French soldiers and bringing them down in the thorn bushes around San Christobal; he received a silver medal and promotion to corporal from Beckwith at a special parade of the 1/95th and held up to them as an 'exemplary soldier' after returning to England from Corunna.

Tom Plunket fought through several close actions during the rest of the war without a scratch. He was wounded by a bullet scarring his forehead at Waterloo, and invalided out of the army with a small pension which he lost by 'expressing his disgust of the size of it to the Lords Commissioners who were induced to strike him off the list altogether'. He married a girl who had a very severe facial disfigurement caused by the explosion of an ammunition wagon at the battle of Quatre Bras, went off to Ireland in the winter of 1815, where starving and penniless he re-enlisted as a redcoat, luckily got a pension of a shilling a day through Beckwith's intervention before taking up the Government's offer to old soldiers of a sum of money and a grant of land to surrender the pension and settle in Nova Scotia.

It was through her that it was discovered that Tom Plunket – once the pride of the Rifle Corps – having returned to England and through drink once again reduced to selling matches, had suddenly dropped dead in the streets of Colchester. Tom's funeral in 1840 and tombstone was paid for by the lady of a retired colonel there; twenty pounds was collected for the widow from other officers resident in the town. [6]

The battle at Cacabelos renewed the will to fight in the ranks of the rearguard. The rise in morale gained through the fight at Cacabelos helped them over the next sixty miles of the terrible Sierra Cebreiro before beginning the drop down to the sea. "Plunket's Shot" probably did grow larger in the telling and retelling of it, but its contribution to the spirit of the rearguard - and to the efforts of the riflemen in the coming years of the war to emulate it – was probably immense.

[1] This speech by Sir John Moore included the rather prophetic sentence (in view of what transpired later) that he was so ashamed of his soldiers that 'he hoped the first cannonball fired by the enemy may take me in the head!'

Richard returned from guiding the ten-day 'Retreat to Corunna' tour in July 1999 which culminated in the first re-enactment of the battle at Corunna itself. During part of the re-enactment display, Richard re-enacted "Plunket's Shot" as a personal tribute, much to the edification of the watching crowd.

More on Plunkett's Shot (FE 52)

|

Many heroic actions by individual soldiers - some unknown - marked the long road from Sahagun to Corunna during that terrible retreat; one of the more famous and well-known concerns an irrepressible and vulgar soul in the ranks of the 95th Rifles.

Many heroic actions by individual soldiers - some unknown - marked the long road from Sahagun to Corunna during that terrible retreat; one of the more famous and well-known concerns an irrepressible and vulgar soul in the ranks of the 95th Rifles.

Edward Paget – commanding the rearguard – ordered disciplinary action taken the next day before his corps dissolved like the rest of the army seemed to be doing. The rearguard were formed after dawn in freezing cold weather in a hollow square out of sight of the road behind a low hill for this to be carried out, with the troopers of the 15th Hussars out keeping a watch on the French in the general direction of Pontferada, supported by a picket of the 95th Rifles.

Edward Paget – commanding the rearguard – ordered disciplinary action taken the next day before his corps dissolved like the rest of the army seemed to be doing. The rearguard were formed after dawn in freezing cold weather in a hollow square out of sight of the road behind a low hill for this to be carried out, with the troopers of the 15th Hussars out keeping a watch on the French in the general direction of Pontferada, supported by a picket of the 95th Rifles.