Lützen 1813:

Prussia Re-enters the Fray

The Battle

by Patrick E. Wilson, UK

| |

The battlefield of Lützen is characterised by a quadrangle of four villages, Gross-Gorschen, Klein-Gorschen, Rahna and Kaja. This is where the main fighting of the day occurred, the area being an undulating plain for the most part, the villages however were generally enclosed by gardens and hedges, the houses though solidly built had thatched roofs and thus easily set on fire. To the north and east of these villages was another important feature of this battlefield, the Flossgraben, a small brook with steep banks. It was no real obstacle to infantry but presented a real barrier to the cavalry and artillery of the era, especially where trees and shrubs lined it. To the north-east of this feature stood the village of Eisdorf, which played a small part in the coming battle. Immediately to the south of the quadrangle of villages stood the height now known as the 'Monarchen Hügel', though it wasn't at the time of the battle. This feature is also of importance as" it was to the south of this height that Wittgenstein had forces form up prior to sending them forward. The height hide the movements of the Allies from the French who were in the quadrangle on the morning of 2nd May and moreover concealed nearly all their subsequent movements from French observation beyond the height. It was the height that the French generals ought to have posted their outposts on but neglected to do so. A final feature of note is to the west of the quadrangle and to the north of the height, a village called Starsiedel, and again it played a small part in the coming battle but nonetheless should be mentioned. General Gneisenau says that the area represented a place then was blessed with natural beauty and abundance, especially on a spring day at the beginning of May, but it was then visited by all the horrors of war. 2

The Allied march to the battlefield, which meant crossing the river Elster, was according to Wittgenstein's orders, a bit of a complicated procedure and as could be expected in such cases led to a number of traffic jams as columns criss-crossed each other. Anyway Wittgenstein's orders have received a fair amount of criticism. Still by about 11.00am on 2nd May, his forward units were in position to attack and only had to advance over the 'Monarchen Hügel' to attack the French in the quadrangle.

Blucher deployed in the first line with Colonel Klux's brigade on the left and General Zeiten's on the right; General Roder's brigade immediately to their rear supported them. On Klux's left both Blucher's and Wintzingerode's cavalry deployed ready to sweep the Lützen plain once the villages of the quadrangle had been taken. General Yorck formed part of the second line with his small corps immediately to the rear of Colonel Klux.

It was probably around noon that Blucher requested permission to launch the attack, Wittgenstein replied in the affirmative and Blucher's Prussians immediately marched off over the 'Monarchen Hügel' toward the quadrangle. The French division before them, taken by surprise in the middle of preparing their afternoon meal, could only scramble to their feet and hastily put the first of the quadrangle villages, Gross-Gorschen, in a state of defence.

Unfortunately the size of the French division, 12,000 men with two batteries of artillery, surprised Wittgenstein in turn who had Blucher deploy his artillery first and bombard the French for about half an hour instead of allowing Blucher and his men to attack immediately with the bayonet. This allowed the French under General Comte Souham, a solid veteran with plenty of combat experience, sufficient of time to get over his initial shock, contact his colleagues for help and get his division deployed, though his artillery was blasted to smithereens.

About the same time as Klux went forward against Gross-Gorschen, Colonel Dolffs Prussian Cuirassiers, supported by Wintzingerode's cavalry, assailed another French division in the area of Starsiedel. Though again when a full blown charge was called for the Allies seemed to have halted and indulged in artillery bombardment which allowed the French again to get over their initial surprise. That the artillery was effective there is no doubt for we have the testimony of one Captain Barres, who was serving in the 3rd battalion of the 47th Ligne Infantry regiment (part of Marechal Auguste Marmont's 6th Corps d'Armée). Which was part of the force that replaced the French division at Starsiedel later that day:

From Barres it is also evident that the Prussian and Russian cavalry conducted many cavalry charges and this seems to have tied down Marmont's Corps d'Armée for the best part of the day. Indeed, it would seem that the charges had shaken Marmont that much that he had asked Napoleon for support about 3.00pm, only to be told that he was mistaken, that he had nothing against him and that the battle turned about Kaja. 4

Meanwhile around 1.00pm, Blucher sensing that Colonel Klux's gallant brigade was tiring sent General Zeiten's brigade to support him on his right towards Klein-Gorschen. General Zeiten's brigade consisted of 7 battalions of infantry, 6 Hussar/Uhlan squadrons and 5 batteries of artillery. Joining up with Klux's reduced brigade, Zeiten led both Prussian brigades forward and pushed the exhausted French division back upon Kaja and took the villages of Rahna and Klein-Gorschen. But their success was to be short lived, for 'Le Rougeaud' (Ney) had arrived with the rest of his Corps d'Armée and promptly counter-at tacked with two fresh divisions in support of Souham. Unable to withstand the numbers that were bought against them, Zeiten and Klux were driven out of their newly acquired prizes of Rahna and Klein-Gorschen back upon Gross-Gorschen.

The 'Rougeaud' pursued at the head of his victorious divisions but was unable to gain Gross-Gorschen, partly because of the quantity of artillery fire that was bought to bear upon his formations, partly because the Prussians used small detachments of cavalry to support their infantry and these endeavoured to find favourable opportunities to charge and partly because the steady fire of the Prussians in platoons was so superior to the fire of the French conscripts. The net effect of this use of all arms and French obstinacy in attack was great slaughter on both sides, and it became evident that Ziethen's and Klux's men could not hold out forever against double their number. Blucher therefore ordered General Roder and the Prussian Guards forward; this magnificent brigade consisted of 8 battalions of infantry, 6 Hussar/Uhlan squadrons and 3 batteries of artillery.

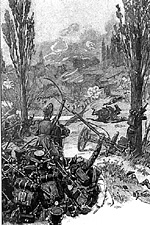

As General Roder moved forward he was joined by all that could from Zeiten's and Klux's much reduced brigades, the Guards advanced with such vigour and bravery that Ney and his three divisions were driven from Rahna and Klein-Gorschen to the very outskirts of Kaja itself. Indeed a battalion of Roder's Guards, probably the Jägers, actually penetrated into Kaja spreading disorder and panic amongst Ney's rapidly disintegrating formations. The field of battle now presented a frightful picture, as General Gneisenau later wrote of the route of the Guards attack: "...the ground over which they marched was strewed with the dead and wounded, and blood and carnage paved the way to glory."

5

Another German writer, von Caemmerer, quoted the dairy of the Prussian Guard Jägers: "The field between Klein and Gross-Gorschen resembled a bivouac where whole battalions had laid down."

6

It was now that the French received reinforcements in the person of Napoleon and his Guards, sensing the crisis of the moment he ordered his aide-de-camp General Georges Mouton (Le comte du Lobau) forward with the reserve division of Ney's Corps d'Armée and the remnants of his other divisions.

Mouton quickly cleared Kaja of Roder's advance units before storming forward to relieve Roder's, Klux and Zeiten's men of possession of Rahna and Klein-Gorschen for a second time. By now these three Prussian brigades were utterly exhausted, having held and defeated twice their number for the past four hours but they still managed to prevent Mouton and his triumphant Frenchmen from capturing Gross-Gorschen. Help was also at hand, Wittgenstein had at last got the Russian reserves onto the field and he immediately released General Yorck's Corps from the reserve. Yorck, who had taken over from Blucher, needed no prompting.

As Blucher would later say of him: "Yorck is a waspish fellow; he does nothing but argue, but when he attacks, then he gets stuck in like nobody else."

7

Of the three brigades immediately available to him, Yorck send two forward, Colonel Horn's (6 battalions of infantry, 4 Dragoon Squadrons and one and half batteries of artillery) were launched into an attack on Rahna and General Hunerbein's (4 battalions of infantry, 4 Dragoon squadrons and one and half batteries of artillery) similarly attacked Klein-Gorschen. They were supported by all that Roder, Ziethen and Klux could muster; again the French were driven from Rahna and Klein-Gorschen back upon Kaja. Prussian units again penetrated this last village of the quadrangle in their pursuit Ney's beaten divisions but this time were bought to a halt by a brigade of Napoleon's Imperial Guard, which the Emperor had sent in to clear the village. This brigade of the Young Guard quickly pushed Yorck's victorious Prussians out of Kaja but stopped there to let the remnants of Ney's Corps d'Armée continue the pursuit alone. The impetus of this counter-attack carried the French again into Rahna and Klein-Gorschen but not Gross-Gorschen as the Prussians fought back hard and eventually gained the upper hand again and drove the French again from Rahna and Klein-Gorschen.

By 5.30pm Yorck's men held a position in front of Klein-Gorschen and Rahna with their right on the Flossgraben and left on the Lützen highway to the north of Rahna. Indeed, Yorck's position was strengthened further by the Russian General Berg occupying Rahna with 5 battalions of infantry, 1 Dragoon regiment and a Russian Position battery, all relatively fresh troops. Meanwhile, Wittgenstein observing French movements to Yorck's right, pushed forward another Russian division to aid the defence of Klein-Gorschen and another to defend the village of Eisdorf, across the Flossgraben to the north of Klein-Gorschen.

These troops were supported by a Russian Grenadier division to the south of Eisdorf, Wittgenstein had intended to outflank the French about Kaja but the troops here soon found themselves under attack from another French Corps d'Armée. The Russians initially found good defensive positions in Eisdorf and amongst the trees and scrub of the Flossgraben but eventually numbers told and they found themselves pushed back across the stream, Klein-Gorschen then became quite indefensible.

It was about this time that Yorck's Prussians, or what was left of them, for it is known that of the 33,000 engaged in the battle over 8,000 became casualties, were subjected to a major onslaught by the French Imperial Guard led by Mortier. The attack itself was preceded by an immense bombardment by 80 guns under General Antoine Drouot, which ended the suffering of many within the quadrangle that day and covered the advance of the Guard.

However Yorck's Prussian brigades held on and met the Imperial Guardsmen with controlled volleys that laid low 1,069 of them and shot Mortier's horse from under him. 8

These fresh troops though, about 10,000 of them, were not stopped by Yorck's controlled volleys and successfully stormed Rahna and Klein-Gorschen. Yorck's Prussians fell back on Gross-Gorschen and beyond, elements of Mortier's Guards getting into Gross-Gorschen itself but being unable to take the whole of the village before night fall put a stop to the fighting. The Prussians were by now very exhausted and almost out of ammunition, the battered brigades of Blucher's Corps falling back under the cover of Yorck's uncommitted brigade. Yorck's brigades, slightly better off then Blucher's, falling back with the Russian divisions that had fought on the Prussian right in the Eisdorf to Klein-Gorschen area. Wittgenstein, still had the Russian Guard, Berg's division that had seen little fighting and masses of cavalry to cover any emergency. But it was evident that his plan had utterly failed and that the French had beaten them this day though it did not feel that way to many of those who had taken part.

The French ended the day equally exhausted, many of their formations were totally disorganised, especially those of Ney and not knowing whether they would have to fight on the morrow. Indeed, Marmont's Corps d'Armée found itself having to fight off a determined cavalry charge at 9.00pm. Poor Marmont was lucky to escape with his life in this instance, as his own men fired him on. The French appear to have lost about 22,000 men in this battle, 15,000 of these belonged to Ney's Corps d'Armée and as a result he was given a day or two to reorganise his corps after the battle. Total Allied losses were about 11,500 killed and wounded, their heaviest loss being Scharnhorst the architect of Prussian military reform. Who it has been argued could have established a reputation to rival that of von Moltke's of 50 years later.

The battle itself is important as it once more established the reputation of the Prussian Army, as Napoleon himself remarked: "These animals have learnt something." 9 Whilst the Russian diplomat von Nesselrode wrote: "The Prussian troops have covered themselves with glory; they have become once more the Prussians of Frederick." 10 Blucher himself was much more succinct: "The French may make wind as much as they please; they are not likely to forget the 2nd May." 11 The Prussian Army had once more arrived on the scene and in the next four campaigns that they would participate in they would add further lustre to their historical military record.

1 Petre, F. Loraine, Napoleon's Last Campaign in Germany 1813 (London: Arms & Armour, 1977 reprint of 1912 edition), p.25.

Barres, Jean Baptist, Memoirs of A French Napoleonic Officer (London: Greenhill 1988 reprint of 1925 edition).

More Battle of Lutzen: 1813

|

General Berg formed the other part of the second line to the rear of Generals Zeiten (at right) and Roder. General Wintzingerode's infantry and when they arrived, General Tormassov's Russian Guards would form a third line. Altogether Wittgenstein's forces would number approximately 73,000 men with over 500 guns, though about 25,000 of these were cavalry and of little value in the village fighting that was to follow.

General Berg formed the other part of the second line to the rear of Generals Zeiten (at right) and Roder. General Wintzingerode's infantry and when they arrived, General Tormassov's Russian Guards would form a third line. Altogether Wittgenstein's forces would number approximately 73,000 men with over 500 guns, though about 25,000 of these were cavalry and of little value in the village fighting that was to follow.

Blucher then ordered his left-hand brigade under Colonel Klux forward; this brigade consisted of 6 battalions of infantry, 6 Dragoon squadrons and 3 batteries of artillery. Colonel Klux rushed forward with his men and easily took Gross-Gorschen from the French but the French counterattacked almost immediately. Klux however held his ground and the French were unable to recapture Gross-Gorschen from the Prussians. It should also be noted that the French division that opposed Klux outnumbered him by about two to one, though of lesser fighting value, being composed almost entirely of conscripts -the 22nd Ligne Infantry regiment excepted.

Blucher then ordered his left-hand brigade under Colonel Klux forward; this brigade consisted of 6 battalions of infantry, 6 Dragoon squadrons and 3 batteries of artillery. Colonel Klux rushed forward with his men and easily took Gross-Gorschen from the French but the French counterattacked almost immediately. Klux however held his ground and the French were unable to recapture Gross-Gorschen from the Prussians. It should also be noted that the French division that opposed Klux outnumbered him by about two to one, though of lesser fighting value, being composed almost entirely of conscripts -the 22nd Ligne Infantry regiment excepted.

The losses amongst the higher echelons of command in both Armies were also beginning to mount, on the Prussian side Blucher had just been wounded, his chief of staff, von Scharnhorst, had just been carried off the field mortally wounded (at right). On the French side, Ney had been wounded by a bayonet thrust in the thigh, his chief of staff, General Goure killed, as had one of his divisional commanders and another had been severely wounded.

The losses amongst the higher echelons of command in both Armies were also beginning to mount, on the Prussian side Blucher had just been wounded, his chief of staff, von Scharnhorst, had just been carried off the field mortally wounded (at right). On the French side, Ney had been wounded by a bayonet thrust in the thigh, his chief of staff, General Goure killed, as had one of his divisional commanders and another had been severely wounded.

Napoleon rallies the conconscripts.

Napoleon rallies the conconscripts.