General Desaix and the

Campaign in Upper Egypt

1798-99

The Campaign in Upper Egypt

by Dave Roberts, UK

| |

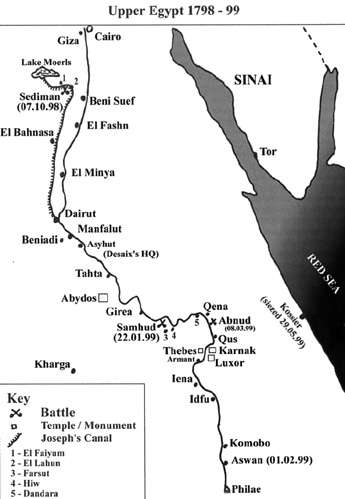

Following the Battle of the Pyramids, Murad Bey withdrew to the south with around 3,000 surviving Mamelukes and whatever treasure they could carry. He did not view the battle as a defeat, simply as a delay in removing the French from Egypt. Murad knew he could raise fresh troops, supplies and money from the provinces in Upper Egypt. The Fellahin had always served the Mamelukes and Murad knew they would be quick to resist the infidels who came pretending to be liberators and friends of Islam. Napoleon could not allow Murad to remain at large. His presence posed little threat to the French position in Cairo and the Delta area, but the population, which Napoleon was trying hard to win over, would never be fully subdued whilst there was the possibility of Murad's return to Cairo. Secondly, the French, now isolated from home by the destruction of their fleet at Aboukir Bay, needed the extra revenue from the provinces of Upper Egypt. In late August 1798, Napoleon gave orders to Desaix to leave Cairo and pursue Murad Bey, destroy his forces and install French rule in the provinces of Upper Egypt. Bonaparte also instructed that scientific information was to be gathered for the newly created Egyptian Institute. Desaix had to constantly reconcile the demands of the scientists and artists accompanying him with the military needs of the campaign. On the night of 24th/25th August, Desaix sailed south from Cairo with 2861 men on foot and 2 light guns on a flotilla of gunboats, galleys, chebels and djerms (traditional Nile sailing craft). Murad's forces were estimated at over 4,000 Mamelukes and twice that again in foot soldiers. After sailing 125 miles south, the flotilla disembarked Desaix and part of his force. Desaix had received intelligence that Murad was at El Bahnasa, on the edge of the Libyan Desert (map below). The French marched across the flooded terrain which separated the Nile from El Bahnasa, spending up to three hours waist deep in water and knee deep in mud. They arrived at El Bahnasa to see the last of Murad's troops ford Joseph's canal and disappear into the desert. The French rejoined the flotilla and sailed a further 135 miles to catch Murad's own flotilla at Asyut. Desaix found no flotilla, but received information that a Mameluke force was camped just 15 miles inland at Beni Adi. When the French arrived, the Mamelukes had left 24 hours earlier. Desaix's troops returned to the Nile and the game of cat-and-mouse continued. Murad was next reported at the El Faiyum basin, a fertile area, north of Beni Adi. Desaix was determined his prey should not escape again and ordered the flotilla to sail back down the Nile to Dairut where it entered the waterway known as Joseph's Canal on 24th September. By 1st October, the French were back at Bahnasa, 70 miles from Dairut. Two days later they encountered a group of Mamelukes and Desaix ordered his men to disembark and follow the Mamelukes on foot. A brief skirmish saw the Mamelukes disperse once more into the desert. Desaix continued north and finally came across Murad at the Coptic monastery of Sediman, near El Lahun. The Battle of Sediman - 7th October 1798Murad's army numbered somewhere between 4-5,000 cavalry, made up of both Mamelukes and Bedouins. He was confident of victory; his army outnumbered the French by nearly two to one and he had received news of the French defeat at Aboukir Bay and of an impending rising in Cairo. Desaix ordered his troops to form the now traditional square, with two platoons of skirmishers on either flank. The lack of cavalry on the French side had little influence on these battles. At the Battle of the Pyramids, and later at Samhud, the cavalry were mere observers, sheltering in the infantry squares, waiting to pursue the fleeing Arabs. The French were accustomed to the Mameluke tactics and relied heavily on their own discipline and marksmanship to resist the ferocious charges. There was always the danger though; that the Mamelukes would penetrate the square, and few dared contemplate the butchery that would ensue. As at the Battle of the Pyramids, if the French square could hold, its superior firepower would soon wilt the Mamelukes maniacal enthusiasm and they would adopt their second tactic; run. Murad's cavalry threw themselves at the square with all their usual vigour and ferocity. The French loosed volley after volley into the charging horde, killing man and horse alike. Several severe dents appeared in the square and vicious hand-to-hand fighting ensued. The heat of the desert and powder dried men's mouths. The ferocity of the battle raged as men thirsted for water. Even the wounded continued to strike at each other, fighting to their last breath. Denon, a civilian who later joined the expedition, told the following story," One of our men, stretched out on the ground, crawled towards a dying Mameluke and slit his throat." When an officer asked him how he could do such a thing, the soldier replied, "I've only a few more minutes to live, and I want to have fun while I still may." Butchery, it seems was not the sole reserve of the Arabs. The battle had been raging for about an hour when a battery of 4 or 5 guns, previously hidden behind a hillock, opened fire on the French square. The situation became desperate and Desaix realised he must advance on the guns or be cut to pieces were he stood. He hesitated, to move the square would be to abandon the wounded to be mutilated, raped and massacred by the Mamelukes. He had little choice and ordered the square to charge. Men pleaded with their comrades not to leave them. Some hung on to coattails, desperately trying to avoid the awful fates, which awaited them at the hands of the Arabs. Some begged to be shot rather than die slowly at the hands of the Mamelukes. The French square charged the Arab guns and carried them easily. The Mamelukes, astonished by the ease with which the French had taken their artillery, turned and fled into the desert once more. The French had lost 24 men killed and around 100 wounded. Murad lost over 400, and withdrew deeper into the Faiyum. Desaix had once again shown himself to be a more than able commander, but this was not the decisive victory he sought. He had inflicted heavy casualties on Murad, but Murad Bey never saw these battles as defeats, merely as setbacks on the road to victory. General Friant, writing in a letter after the battle, commented, "I believe that General Desaix is ten degrees cooler than ice." [1]

Desaix ordered a pursuit to catch Murad in the Faiyum, but elusive as ever Murad was at El Lahun when Desaix was in the Faiyum and was at Bahnasa when Desaix returned to El Lahun on October 11th. Desaix, frustrated by four days fruitless searching, wrote to Napoleon, "I would be glad to continue the pursuit of them, but really this would be very difficult at the moment. The inundation, which cuts me off from the villages, would make it impossible for me to feed the troops...The canal is no longer navigable, and my sick cause me a great deal of embarrassment. The eye disease is truly a horrible plague: it has deprived me of 1,400 men. In my last marches, I have dragged with me about a hundred of these wretches who were totally blind.... We are practically naked, without shoes, without anything. The troops really need a rest. Give us the supplies and the means, and we shall go on . . . What do you want me to do?" [2]

The situation had become desperate in Desaix's eyes. His troops were suffering great hardships and he still had not won a convincing victory over Murad. For once Napoleon agreed, and ordered Desaix to rest his troops and take time to "organise" the Faiyum. By organise, Napoleon meant for Desaix to levy taxes from the population and requisition necessary supplies. Desaix re-entered the Faiyum at the end of October and began to carry out Napoleon's orders. This area had only recently been "organised" by Murad, during his stay there and some elements of the population felt they were being "organised " once too often. On November 8th, 500 French troops, a third of them suffering from ophthalmia, were besieged in the capital, El Faiyum by several thousand fellahin. The French lost four dead and 200 wounded, before the attack was repulsed.

By November 20, Desaix had evacuated the now thoroughly "organised" Faiyum and moved his division to Beni Suef, where he established a base and awaited reinforcements from Cairo. The reinforcements had in fact, left Giza on November 8th, the same day the French troops were defending El Faiyum against several thousand angry taxpayers, and were commanded by General Belliard. His force consisted of a battalion of infantry and arrived at Beni Suef towards the end of November, to await the return of Desaix who had gone to Cairo to plead in person for desperately needed troops.

Desaix returned to Beni Suef on December 9th. His Division had already received 800 replacements, and on December 10th, 1,000 cavalry under the command of General Davout joined it. With his troops rested, reinforced and re-supplied, Desaix set out again towards Aswan. His flotilla, which had also been reinforced, left at the same time under the command of Captain Guichard. The shoals and sandbanks of the Nile, meant that the flotilla soon fell behind the main force and Desaix did not see it again until January 19th at Girga.

Two civilians, both with very different agendas for the expedition, had joined Desaix's forces at Beni Suef. The first was the savant, Vivant Denon, a member of the newly created Institute, who was to study and record the various temples and ancient sites along the Nile. The second was a Copt, Moallem Jacob. Officially in charge of tax collecting in Upper Egypt, Jacob was in fact the joint commander of the expedition. He acted as an advisor and interpreter to Desaix. Having served one of Murad's colleagues, Soliman Bey, he had a detailed knowledge of the country, its people, and Desaix's opponent. Desaix made full use of "The Copt", as he became known to the French, realising that if he was to succeed against Murad, he would need all the help he could get. Moallem Jacob was a shrewd diplomat and was an able soldier.

When a Coptic Legion was formed after Napoleon's departure from Egypt, Jacob was appointed its commanding general.

The French arrived in Asyut on Christmas Day 1798, having marched an average of 25 to 30 miles a day. Conditions had improved little, the soldiers' shoes wore out and although the days were still hot, the nights were now cold enough for a frost. After only nine days marching over 200 soldiers were sick with dysentery, ophthamlia or both. Asyut provided some relief for the French though. The area was much more cultivated than Lower Egypt and there were many palm groves and orchards for shelter and fresh food.

Whilst at Asyut, Moallem's spies informed him that Murad was boasting he would await the French at Girga, and destroy them. Desaix ordered his troops to march on Girga, about 80 miles to the south. They arrived on December 29th, to discover Murad had once again disappeared, taunting the French to follow him. Without the supplies travelling onboard his flotilla, Desaix could not continue the pursuit, and was forced to call a halt and await the arrival of Captain Guichard's boats.

While the French remained at Girga, Murad began to gather fresh allies and troops to his cause. From his camp, about 35 miles south of Girga, he wrote to his sworn enemy, Hassan Bey persuading him to abandon their feud and join against Desaix. He wrote to the sheriffs of Yambo and Jidda for troops, his agents bought slaves in Nubia to swell his ranks and everywhere his messengers called on the fellahin to rise against the infidel invaders. Murad even enlisted children, using them to steal weapons from the French in Girga.

Murad's most notable allies were the Arabian warriors from Hejaz. These 'Meccans' as the French called them, were ferocious fighters armed to the teeth with muskets, sabres, lances and daggers. Bonaparte wrote of them, "Their ferocity is equalled only by the misery of their standard of life, exposed as they are, day after day, to the hot sand, the burning sun, without water. They have neither pity nor faith. They are the picture of savage man in the most hideous form imaginable." [3]

On January 19th, The French flotilla finally arrived and two days later, Desaix ordered his division to move south. On January 22, Murad met the French at Samhud with a force of 3,000-foot soldiers, 7,000 mounted Arabs, 2,000 Meccans on foot and 2,000 Mamelukes.

More Desaix 1798-99

Desaix 1798-99: The Campaign in Upper Egypt Desaix 1798-99: The Battle Of Samhud - 22 January 1799 Desaix 1798-99: The Battle Of Abnud - March 8th 1799 Desaix 1798-99: Order Of Battle - Desaix's Division, December 1798 Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #50 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2000 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |