Lannes' Battle in the Mud

Pultusk 1806

by Patrick E. Wilson, UK

| |

Following the French triumph of Jena-Auerstädt, Napoleon hoped to reach Poland and inflict a decisive defeat upon Prussia's ally before the on set of winter in 1806. The first of these objectives was easily attained as Prussia's ally, Russia, had been rather slow in the mobilisation of their armed forces, and anyway they had considered themselves as only auxiliaries to the mighty Prussian war machine. (Now apart from L'Estocq's East Prussian Corps d'Armée, that war machine was none and the forces of Holy Russia would have to supply the main effort against the Corsican ogre).

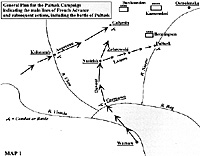

Large Pultusk Operational Map (slow: 50K)

Napoleon followed a few weeks later and in mid-December decided to cross the Vistula in an attempt to envelop the Russian Army and pin it against the river Narew as it retired before his forces. This plan was to go astray for a number of reasons, namely the state roads and the weather.

The roads being for the most part mere dirt tracks, Bourienne, Napoleon's Governor of Hamburg, recorded: "All the letters I received were nothing but a succession of complaints on the bad state of the roads." Napoleon himself commenting that he had discovered a new element in Poland - Mud! The weather during this period was a continual succession of frosts and thaws interspersed with showers of snow, sleet and icy cold rain. This continual fluctuation in the weather rendered the Polish road system and countryside a place of misery to the average French soldier, many developing a aversion fur the place and not a few committing suicide rather then face such conditions, From a purely military point of view the weather made the transportation of supplies and artillery a near impossible task, which strained the determination of the most determined individuals. Whole artillery teams sunk into morasses of mud, many horses actually drowned and many guns had to be abandoned. It effected the Russians and French equally and the French at least could profit from this by using guns that the Russians had had to abandon, not that that was much comfort to the average infantry soldier shivering in his often cold bivouac and covered in the ubiquitous coating of mud.

The net result of this logistic nightmare was that Napoleon's advance out behind schedule and lost, at least in some cases, all sense of co-ordination. Some Corps D'Armée achieving their objectives despite innumerable obstacles but others falling behind schedule and consequently endangering their comrades by dropping out of supporting distance. It also allowed the Russians breathing space and time to concentrate prior to falling back on their main supply depots in East Prussia and Poland, or time to plan an attack that could destroy the French forces piecemeal. It was within this environment that Marshal Jean Lannes set out with his 5th Corps d'Armée on Boxing day 1806 fur the Polish town of Pultusk.

Instructions

Lannes instructions were to proceed to Pultusk, cross the river Narew and then construct a bridgehead there. Napoleon had no inclination of the serious resistance that Lannes would meet there, indeed he believed the Russians to be falling back towards Strzegoczin and Golymin and had directed the main body of his forces in that direction. Lannes would at the most encounter a few scattered regiments, which he could easily capture. In fact, General Levin August Benningsen and his whole Corps of 40,000 men and 128 guns held Pultusk in strong positions and were determined to hold their ground. The scene was set for a major engagement that Napoleon for one anticipated would take place, if at all, in another place.

Benningsen had decided to hold his ground despite orders to the contrary from his commanding officer, Marshal Kamenskoi, a gallant but worn-out colleague of Suvorov, who had ordered a retirement on Ostrolenska. Marshal Frederich Wilhelm Buxhowden, the other senior officer present, faithfully carried out his orders with the divisions under his command, although some of his units got sucked into the rearguard action of Golymin which occurred on the same day as the Battle of Pultusk.

Meanwhile Benningsen had selected the ground to the North-west of Pultusk fur his battle against the French, this around, the Heights of Mosin, offered a good defensive position that enabled the defending general to conceal troops in depressions in the ground as well as the large wood to the south of the village of Mosin. Benningsen positioned the main body of his troops on the road that ran from Pultusk to Golymin and passed to rear of the heights, and then through the large wood mentioned above. Benningsen drew his troops up in three lines, the first consisting of seven infantry regiments from his 2nd and 3rd divisions, the second of six infantry regiments and the third of two infantry regiments from the 5th and 6th divisions. Artillery was placed in advantageous positions within the first line.

Benningsen also established two advance guards, the first under General Bagavout to protect Pultusk and the bridge there, consisted of three infantry regiments, some Dragoons, some artillery and 600 Cossacks, and was positioned to South-west of Pultusk on the southern edge of the Mosin heights. The second advance guard was under General Barclays de Tolly and occupied the large wood and the village of Mosin, it consisted of three Jäger regiments, a musketeer regiment, the Polish Uhlan regiment and a couple of batteries. Connecting these two advance guards, Benningsen had deployed his regular cavalry along the crest of the Mosin heights, to the front of this cavalry stood along line of Cossacks. The cavalry itself masked the artillery of the main body drawn up along the Pultusk to Golymin road.

Advance

On the morning of 26th December 1806, Marshal Lannes started his advance upon Pultusk at 7.00am, his Corps D'Armée had only about five miles to traverse but the weather had been atrocious, a thaw had set in, there was a constant shower of rain, sleet and snow which turned the roads and surrounding countryside into a sea of mud that made movement not only difficult but almost impossible. Artillery had to be drawn with double, tremble and even quadruple teams, infantry took an hour to traverse a mile and a quarter. Lannes himself wrote that the rain and hail had overwhelmed his men, and yet, his Corps D'Armée had managed to keep its artillery up with them and the men were confident of victory under their intrepid Marshal.

Lannes accompanied his advance guard of a couple of squadrons of cavalry, brushing aside some Cossacks, Lannes had his first sight of the battlefield, the heights of Mosin (Pultusk was hidden by rising ground) and Benningsen's forward positions. What he saw did not bode well but he had Napoleon's clear orders to seize Pultusk and set about organising his men for attack as they slowly came up. Placing his 1st Division under General G.L. Suchet in the first line, he deployed it as follows: General M. Claparede with his 17th Legere Infantry regiment supported by General A.F. Treilhard's hussars opposed General Bagavout, General D. Vedel held the centre of the line with the 64th Ligne and a battalion of the 88th Ligne and General H. Rielle with the 34th Ligne and the other battalion of the 88th Ligne opposed the large wood south of the village of Mosin. General Rielle was accompanied by Suchet and later Lannes in person. General Becker and 12 squadrons of Dragoons moved to support General Rielle and General H.T. Gazan formed a second line with his 2nd Division and the 40th Ligne regiment of General Rielle's brigade. This second line consisted of 11 battalions.

This deployment took some time because of the weather, the day was a miserable one full of icy showers of snow and sleet, and it was not until 11.00am or possibly later that the French were ready to mount an attack.

General Claparede and the 17th Legere were the first to move forward, easily brushing aside Bagavout's Cossacks and Dragoons, and making short work also of the 4th Jägers that Bagavout now opposed them with. But then Benningsen intervened, ordering General Ostermann-Tolstoi to counter-attack with a regiment from the main body.

Simultaneously with these developments, General Vedel had advanced with his battalions in support of Claparede's attack on Bagavout but in doing so he had exposed himself to attack from Benningsen's cavalry on the Mosin heights.

The Russian cavalry General Koschin led several squadrons of regular cavalry to attack Vedel's infantry, concealed by a flurry of snow Koschin's cavalry severely cut up the 64th Ligne before the 88th Ligne could to save their comrades of the 64th from the Muscovite sabres. Meanwhile on Bagavout's front the 17th Legere and Ostermann-Tulstoi's regiment had came to blows and a fearful hand-to-hand fight had developed in the swirling snow, each side claimed to have defeated the other but what is certain is that Vedel's depleted battalions had fallen back and uncovered Claparede's flank, thereby forcing that General to retire. General Treilhard's hussars now advanced to cover this retirement and compelling Ostermann-Tolstoi's infantry and Kuschin's cavalry to fail back to their original positions. However as Treilhard's hussars advanced, the Russian Hussar regiment Isoum moved aside to unmask a powerful battery of artillery from the main body, this inflicted severe casualties on Treilhard's hussars and forced him in turn to retire.

Whilst this confusing fighting was going on to the South-west and west of Pultusk, General Rielle's forces, now accompanied by both Suchet and Lannes, had attacked the large wood defended by General Barclay de Tolly's Jägers. Rielle's 34th Ligne regiment, one of the finest in the French army and present at both Austerlitz and Jena, went forward behind a swarm of voltigeurs and supported on the left wing by the 21st Chasseurs a cheval, burst upon Barclay de Tolly's Jägers like a sudden thunderstorm. The Jägers, though fighting furiously from tree to tree were driven back by the force of the onslaught, the 34th Ligne momentarily gained possession of a Russian battery as well as most of the wood before Barclay de Tolly's position was saved by a counterattack by the Musketeer regiment Tinghin and the Polish Uhlan Regiment.

This attack recaptured the Russian battery captured but moments before and sent the 34th Ligne and 21st Chasseurs a cheval tumbling back upon their supports, again a battalion of 88th Ligne intervened to save the situation and the combat in the wood degenerated into a free for all fire-fight, the French, just holding their own and their position in the wood. But casualties were heavy, Lannes himself was grazed by a musket hall, his aide-de-camp Vuslin was killed, as was Suchet's M. Curial. Whilst General Becker's Dragoons lost a number of senior officers including General of Brigade Boulsard and Colonel Barthelemy as they moved up to support Reille's battered formations.

No Gain

Thus after several hours fighting the French had failed to make, or even hold, any significant gain on the battlefield. General Gazan's division had just come into line and occupied the Mosin heights opposite Benningsen's main position. Gazan's advance had driven Benningsen's regular cavalry from heights but in turn exposed his own men to the full fury of Benningsen's artillery situated along the main Russian position. Gazan's men suffered accordingly and their own artillery could but make a feeble reply. Indeed with the French checked all along the line, Lannes wounded and the reserves almost used, it looked as if disaster stared the 5th Corps squarely in the eye.

Fortunately, fate had other ideas, General the Marquis d'Aultanne, Davoust's Chief of Staff and temporarily in command of his 3rd Infantry division. Heard, just as he was about to camp for the night, a heavy cannonade to his right which indicated that Marshal Lannes most be seriously engaged. With great promptitude d'Aultanne resolved to march to his assistance, this was not as easy as it sounds, as d'Aultanne had to use the same atrocious roads as Lannes but these were also blocked by abandoned Russian guns and wagons, and as result d'Aultanne did not reach the Pultusk battlefield until 2.00pm. Benningsen was not unaware of his approach and had wheeled back his right flank to counter this new threat, he had also despatched 20 squadrons of regular cavalry to support Barclay de Tolly in his position. Benningsen's re-deployment had an effect upon the main engagement, in that by pulling back some units he lessened the amount of fire that his forces directed upon Gazan and therefore aided that General in his efforts to hold on under fire.

General the Marquis d'Aultanne lost little time in contacting Lannes upon his arrival and advanced upon the village of Musin with his 9 battalions in the midst of yet another heavy flurry of snow, charged by the Polish Uhlans, d'Aultanne's men made short work of these by now exhausted horsemen and continued their advance but were halted again by the arrival of more Russian cavalrymen. Barclay de Tolly had been reinforced by two musketeer regiments, Tchernigov and Litver, with these troops and the arrival of a fresh artillery battery bought up personally by Benningsen. Barclay de Tolly at last regained full control of the large wood, ejecting General Rielle and the gallant 34th Ligne fur the last time. This movement left a gap between Rielle and d'Aultanne into which poured the 20 squadrons of cavalry sent by Benningsen, this could have been disastrous for both Lannes and d'Aultanne but they were saved by the conduct of the 85th Ligne regiment, which, as if to make up for their near rout at the Battle of Auerstädt, stood firm against the Russian cavalry onslaught.

The time thus gained allowed both Lannes and d'Aultanne to stabilise their respective fronts. The last Russian cavalry attacks in this sector occurred about 8.00pm amidst another ubiquitous flurry of snow, afterwards d'Aultanne retired to the woods to his rear for the night. Elsewhere, Claparede and Vedel had attacked Bagavout again, this time supported Gazan's artillery which cannonaded Bagavout's right flank. Bagavout was unable to hold out against this fresh onslaught and fell back abandoning his cannon, Ostermann-Tolstoi promptly threw in two fresh regiments of infantry and supported them with artillery fire. The French were checked and after another fearful hand-to-hand fight compelled to relinquish their gains, including Bagavout's artillery. A final bayonet charge led by Major-General Somow with the Touler Musketeer regiment completed the repulse of Claparede and Vedel, who both ended the day with wounds from the severe hand-to-hand fighting of this sector. This attack occurred about the same time as Lannes and d'Aultanne were beset by the Russian cavalry.

Gradually the fighting began to die down along the Mosen heights and on d'Aultanne's front and the French, weary and dispirited fell back to their starting positions. They had been repulsed by a superior force in a strong position and had fought hard under the eyes of a commander they adored, they had lost about 8,000 men including prisoners. Among their wounded was their esteemed commander, Marshal Jean Lannes, who would be out of action until the spring.

During the night Benningsen decided to retreat on Ostrolenska in compliance with his original orders, he believed he had been attacked by Marshals Murat, Davoust and Lannes with 50,000 men and had he been supported by Marshal Buxhowden and the rest of the Russian army, he would have gained a greater victory than that which he believed he had attained. Only lack of supplies obliged him to retreat, a retreat that was not interrupted by the enemy, which led him to infer that the enemy must have suffered severe losses. He put his own at 3,000 men killed but did not state the number of wounded.

The Battle of Pultusk brought chief command of the Russian armies to Benningsen, despite the fact that Buxhowden was his senior, Kamenskoi had been invalided home no longer quite right in the head, the stress of responsibility perhaps too much for him. Buxhowden was recalled too so that Benningsen could have chief command and is now chiefly remembered for his dismal performance at The Battle of Austerlitz. Pultusk is therefore quite important in this context, had Lannes been successful then Benningsen certainly would not have received the chief command and the entire campaign in Poland would have taken a different course with Buxhowden in command.

Pultusk and its sister engagement, the combat of Golymin, ruined Napoleon's plan to envelop the Russians and push them into the Narew river. As repeatedly stressed this was as much the result of the atrocious weather and bad Polish roads, as direct contact with forces of Holy Russia. It was also a grim foretaste of things to come, as the Battles of Heilsberg and Eylau would show, defeating the Russian army was no easy matter. The poor performance of the Russian army at Austerlitz had been just a blimp and for the rest of the Napoleonic wars the Russian army fought with the obstinacy and bravery that has characterised it ever since. Pultusk silenced the scoffers and give Napoleon something to think about.

Pultusk 1806 Order of Battle and Tactical Map

|

Napoleon's advance guard under Marshal Murat entered Warsaw on 28th November 1806.

Napoleon's advance guard under Marshal Murat entered Warsaw on 28th November 1806.