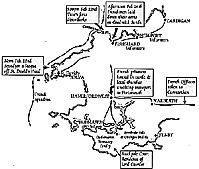

After he had put down the civil war in Le Vendée, Lazare Hoche decided to take the war onto British soil. In 1796 he planned a full scale invasion of Ireland, which would be supported by the United Irishmen. An expedition of 15,000 men was organised and to prevent British reinforcements being sent to Ireland and to create panic on the mainland two smaller expeditions were planned. A force of 5,000 men under Quantin would cross the North Sea from Dunkirk, win the support of the industrial working classes and march across northern England to Lancashire. Here they would link up with a smaller expedition, which would either have attacked Bristol or failing that, would have landed in Cardigan Bay and threatened Liverpool. It was predicted that the Welsh and English working classes, like their Irish counterparts would rise in the name of Liberty.

Larger Version of Map (slow: 60K)

French Invasion Force

Preparations went ahead in Brest but with the failure of the Irish expedition it is difficult to see why it set sail at all. It seems to have been Hoche's own private show. Equally strange was the choice of its leader, a little known American of Irish descent called William Tate. During the American war he had served as Captain-Lieutenant in the 4th. Regiment of South Carolina.

However, he became deeply embroiled in French plans for the capture of New Orleans from Spain and fell foul of the American authorities who wanted no part of it. In 1795 he fled to Paris, hoping to be reimbursed for his expenses and demanding confirmation of his rank (In Paris he became friendly with Wolfe Tone of the United Irishmen.) Hoche thought that Tate was the right man to lead the Bristol expedition and he was appointed Chef de Brigade.

In British Uniforms

Most of the expedition was to be kitted out from the stock of British uniforms captured earlier at Quiberon Bay. But these would only take brown dye so La Seconde Legion des Francs became known as "La Legion Noir" or the "Black Legion". The force consisted of a mixture of 200 "Chouans" from Le Vendée; 400 republicans and 564 deserters, émigrés and criminals. They were divided into twelve troops, two of which were grenadiers. A few of the officers were Irish. The force was at least 1,233 strong and well armed.

The quality of the squadron of four ships under Chef de Division, Commodore Jean Joseph Castagnier was impressive. Le Vengeance and La Resistance were two of the largest and newest French frigates and the only examples of their type. The latter was on her maiden voyage. The corvette La Constance and the lugger Vautour were also new. Castagnier had, like Hoche, defended Dunkirk against the British. Castagnier's instructions were to head for Dublin roads after disembarking the soldiers. But after the failure of the Irish expedition, one wonders why his orders remained unchanged.

Hoche's detailed instructions undoubtedly asked far too much of this expedition. Having burnt Bristol, the force was to land on the Welsh side of the Bristol Channel or Failing this, in Cardigan Bay and make for Chester or Liverpool. Apart from this the working classes were to be encouraged to rebel; Britain's trade was to be dislocated and French prisoners of war liberated, causing such chaos as to make the invasion of Britain possible. Hoche warned Tate that he should not risk battle unless it was absolutely essential, since the enemy would have superior forces.

Flying Russian Colours

The squadron left Brest on February 16th. 1797. Flying Russian colours they lurked around Lundy, sinking a few small craft while waiting for a suitable tide to take them to Bristol. Skilfully using the tides to reach Porlock, Castagnier was finally forced to abandon the project because of adverse winds. The inhabitants of Ilfracombe sounded the alarm and the North Devon Volunteers were mustered. Tate now insisted on making for Cardigan Bay. However, there had been several sightings of the ships and the Admiralty, Plymouth, Bristol, Milford and Cork had been alerted.

Possibly an attempt to bring cannon ashore caused casualties. A company of grenadiers under Irishman, Lieutenant St. Leger rushed a mile inland and took over Trehowel Farm, which became Tate's headquarters. La Seconde Legion des Francs 1 had succeeded in making the last landing by enemy soldiers on the British mainland.

When one of the French ships, probably Vautour entered Fishguard Bay to reconnoitre, Fishguard Fort fired a blank shot. Whether this was the customary signal to a visiting British vessel or the alarm for the Fishguard Volunteers, it saved Fishguard!

Larger Version of Map (slow: 74K)

The ship promptly hoisted the French tricolour and sailed away to rejoin the others. Although the Fort had eight 9pdrs., there were only three rounds in the magazine and the small port could have been easily taken.

Volunteers

With the loss of the American colonies, the last Under Secretary of State, William Knox, decided in 1784 to purchase estates in Pembrokeshire and his mansion at Llanstinan was only 4 miles from Fishguard. When the Government called for volunteers, Knox raised the Fishguard and Newport Volunteer Infantry 2 in 1794, one of the earliest in the kingdom. Having raised four companies, totalling nearly three hundred men, it was the largest force in the county and his son Thomas Knox was appointed Lieutenant Colonel. At the time of the French landing, Knox was 28 years old, and apart from dealing with food riots, had no combat experience. As the seriousness of the situation dawned on him he instructed the Newport division to march the 7 miles to his headquarters at Fishguard Fort.

Lord Cawdor was 30 miles away at Stackpole Court in the far south of the county when he received the news at 11pm. In 1794 he was commissioned captain of the Castlemartin Troop of the Pembroke Yeomanry Cavalry (47 men) which fortunately was assembled for a funeral on the following day. He immediately mobilised all the troops at his disposal and crossed Pembroke Ferry with Major Ackland's Pembroke Volunteers (96 men) and Colonel James' Cardiganshire Militia (103 men). (The Royal Pembrokeshire Militia were serving at Landguard Fort, Harwich at the time).

Once across, Cawdor went ahead and met 55-year old Lord Milford, the Lord Lieutenant of the county and captain of the Dungleddy Troop of the Yeomanry, which still had not been formed three years after their creation. Milford delegated full authority to Cawdor.

Larger Version of Uniforms (very slow: 191K)

Having summoned the troops to Haverfordwest, he had galloped the 16 miles to Fishguard to assess Knox's situation. Satisfied that Knox was taking appropriate measures, he returned to Haverfordwest to supervise the arrival of the local forces. Captain Longcroft of the navy brought in the press gangs and the crews of two revenue cutters at Milford, totalling about 150 sailors. Nine 9 pdr. cannons were brought ashore by the sailors, of which six were placed in Haverfordwest castle, the others were brought along.

Due to Colby's exertions the force, under Cawdor, set off at noon, February 23rd. from Haverfordwest to reinforce Knox, who was facing the French at Fishguard with his Fishguard Volunteers.

Knox had declared his intention of attacking on the following day if he was not heavily outnumbered. Colby wrote later that he had suggested placing troops on the heights opposite the French to discourage them from moving until reinforcements arrived. Knox denied this but had sent out scouting parties to assess the French strength.

The French had moved a further two miles inland and occupied two strong defensive positions at Garnwnda and Garngelli, both are high rocky outcrops giving an unobstructed view of the surrounding countryside. Thus far all had gone well for Tate and his force.

Overwhelming Force

On the morning of February 23, a hundred of Knox's men had still not arrived and he soon learned that he was facing an enemy of over 1200 men, who could have been seasoned veterans. This was a different proposition to the skirmishing role of their training. Although many inhabitants were fleeing the area in panic, hundreds of civilians were flocking into the area armed with a variety of crude weaponry.

Poor Knox faced a dilemma - to attack, or to defend Fishguard, or to retreat towards his reinforcements, which he knew would be moving towards him from Haverfordwest. He decided to retreat slowly towards Haverfordwest. He gave orders to spike the Fort's cannons, (which the Woolich Bombardiers refused to carry out) and about 9 a.m. he set off, sending out scouts to keep watch on the French. The Defence Committee at Haver-fordwest agreed with this decision, which was to have grave repercussions for Knox later. Fishguard was now completely at Tate's mercy.

Knox and his 194 men met the reinforcements led by Lord Cawdor and Colby at Trefgarne (8 miles from Fishguard) at 1.30 p.m. Colby was surprised to see him. After a short dispute Cawdor was accepted as commander in chief and he led the British forces back towards Fishguard, with Knox's Volunteers bringing up the rear.

Attack

By 5 p.m. the force had arrived within a mile of Fishguard and Cawdor decided to attack. Considering the darkness, this was indeed risky to say the least. The 600 men, dragging their cannons marched up the narrow Trefwrgi Lane, with its high hedges, towards the French position on Garngelli. But a French advance party under the Irishman, Lieutenant St. Leger had prepared an ambush.

A volley poured into the column at point blank range would have resulted in heavy casualties. Boxed into the lane, the force was in a death trap. Seemingly oblivious to this, Cawdor decided to withdraw to Fishguard, since they were losing their bearings in the darkness and avoided the ambush awaiting him by a few hundred yards. So the force prepared to spend the night in Fishguard, the officers were based in today's Royal Oak Inn.

However, all had not gone well for Tate. Many of his foraging parties had resorted to pillaging the local farms and ill-discipline was getting out of hand with examples of mutinous men threatening their officers. It was also obvious to Tate that the local Welsh peasants were hostile to his force of "liberators" and six peasants and soldiers had been killed in clashes. Many of the Irish officers were counselling surrender, realising what would be in store for them if hostilities continued.

The departure of Castagnier's squadron as planned for Ireland had shocked and demoralised the men, who had seen their escape route vanish over the horizon. There is strong evidence that the French were deceived by the appearance in the neighbourhood of large numbers of local womenfolk wearing the traditional dress of red shawls and black hats, which at a distance resembled infantry uniforms. It is certain that inhabitants over a wide area were flocking towards Fishguard to attack the enemy.

That evening, two French delegates arrived at the Royal Oak to negotiate a conditional surrender. Tate wrote:

To the Officer commanding His Britannic Majesty's Troops. 5th. year of the Republic.

Health and Respect, Tate. But Cawdor with magnificent bluff replied that with the superior numbers at his command, which were increasing hourly, he would only accept an unconditional surrender and gave an ultimatum of 10 a.m.. On the following morning the British force was lined up in battle order, undoubtedly reinforced by hundreds of civilians, to await Tate's response.

Tate accepted the terms and at 2 p.m., Friday 24th February 1797, with drums beating but without their banners, the French marched down to Goodwick beach where they stacked their weapons. At 4 p.m. the French prisoners were marched through Fishguard on their way to temporary imprisonment in Haverfordwest. Meanwhile, Cawdor had ridden to Trehowel Farm and received Tate's surrender, although the document has never been found. The officers were taken by a different route from the men, first to Haverfordwest and then on to Carmarthen. The last invasion of the British mainland had ended. To justify their surrender the French officers wrote :

On this day 25 February in the fifth year of the French Republic, we the officers of the 2nd Legion of France;

In view of the indiscipline of the troops and the impossibility of equipping ourselves;

In view of the ultimate impossibility of raising the resistance necessary for success, before an enemy which has risen en masse with troops of the line numbering several thousand, when we only possess twelve hundred whose ranks dwindle daily through illness and desertion. Finally, in view of instances wherein soldiers, who remain undetected, committed the act of firing shots upon their superiors.

We the Officers present, convinced of the commendable conduct, integrity and fairness of Citizen Tate, Commander-in-Chief of the 2nd Legion of French, testify that he employed every necessary and plausible means of restoring order and that in spite of his and our united efforts, was unable to achieve the glorious objective towards which our honour called us. He now finds himself forced, by the British summons, to surrender as a prisoner of war. In witness we have drafted and signed the present statement to serve him as needs be.

Signed by the Officers.

Tate Commander-in Chief After his surrender and brief imprisonment in Portsmouth, Tate was returned to France in a prisoner exchange in 1798. He was involved in bitter wrangling with the French authorities over his rank and was finally awarded half pay status. He was last mentioned in 1809 when his debts were cleared by his friends and the old man sailed back to America.

Castagnier had sent Vautour back to France with his dispatches. En route to the Dublin roads his squadron encountered a convoy. They sank eleven ships and took 400 prisoners. Having dallied too long in Irish waters Castagnier aboard Le Vengeance made it safely into Brest but La Constance, helping the La Resistance, crippled by storm damage, were intercepted by two British 36 gun frigates St. Fiorenzo and La Nymphe. In the uneven action which ensued La Resistance suffered 10 killed and 9 wounded and La Constance, 8 killed and 6 wounded, before they surrendered.

Undoubtedly, Lord Cawdor was the hero of the hour. He, Knox and others were congratulated, received the royal gratitude from George III and countless local honours. However, a whispering campaign started against Knox and eventually in May 1797 he challenged Cawdor to a duel which was probably not fought.

In May the Pembroke Yeomanry (224 Sqn.) R.L.C., will receive the Freedom to Enter the twin towns of Fishguard and Goodwick in an impressive regimental and civic ceremony. The Napoleonic Association will be participating in a two day event in Fishguard on 30-31 August, the first day will involve a re-enactment of the events of February 1797. As one of the early events, on February 22-23 a march will be undertaken retracing the route of the units by marching from Stackpole to Fishguard.

1. A document signed by Hoche indicates that the French were divided into 12 troops, each with 3 officers, 1 Sgt. Major, 2 Sergeants, 1 Corporal (fourier), 1 ordinary Corporals and 1 Drummer.

P. Carradice. The Last Invasion. Village Publishing

Related

Beginning in February and continuing until November, Pembrokeshire in general and Fishguard in particular will be the centre of an exiting programme of events to commemorate the bicentenary last invasion of mainland Britain, which took place in February 1797. In this article Bill Fowler, Chairman of the Bicentenary Committee throws some light on the affair.

Beginning in February and continuing until November, Pembrokeshire in general and Fishguard in particular will be the centre of an exiting programme of events to commemorate the bicentenary last invasion of mainland Britain, which took place in February 1797. In this article Bill Fowler, Chairman of the Bicentenary Committee throws some light on the affair.

In December 1796, Hoche's expedition arrived in Bantry Bay but was scattered by bad weather and limped back into Brest. A combination of poor weather and indiscipline resulted in the abandonment of Quantin's expedition. But what of the other expedition?

In December 1796, Hoche's expedition arrived in Bantry Bay but was scattered by bad weather and limped back into Brest. A combination of poor weather and indiscipline resulted in the abandonment of Quantin's expedition. But what of the other expedition?

By noon on Wednesday 22nd February, Castagnier was spotted rounding St. David's Head in Pembrokeshire, flying British colours. At 4pm. the French anchored in perfect weather off Carreg Wastad, a rocky headland and bay three miles from Fishguard. By 2am. on Thursday 23rd. February, 17 boatloads of troops, 47 barrels of powder, 50 tons of cartridges and grenades and 2,000 stands of arms had been brought ashore.

By noon on Wednesday 22nd February, Castagnier was spotted rounding St. David's Head in Pembrokeshire, flying British colours. At 4pm. the French anchored in perfect weather off Carreg Wastad, a rocky headland and bay three miles from Fishguard. By 2am. on Thursday 23rd. February, 17 boatloads of troops, 47 barrels of powder, 50 tons of cartridges and grenades and 2,000 stands of arms had been brought ashore.

Most of the credit for gathering 400 soldiers and sailors at Haverfordwest was due to the energy of Lieutenant Colonel Colby of the Pembrokeshire Militia, who was training the Supplementary Militia.

Most of the credit for gathering 400 soldiers and sailors at Haverfordwest was due to the energy of Lieutenant Colonel Colby of the Pembrokeshire Militia, who was training the Supplementary Militia.

The Circumstances under which the Body of the French troops under my Command were landed at this Place renders it unnecessary to attempt any military operations, as they would tend only to Bloodshed and Pillage. We therefore desire to enter into a Negotiation upon Principles of Humanity for a surrender. If you are influenced by similar Considerations you may signify the same and, in the meantime, Hostilities shall cease.

FRENCH ARMY

LIGHT INFANTRY

FRENCH ARMY

LIGHT INFANTRY In 1853 Lord Palmerston conferred upon the Pembroke Yeomanry the battle honour "Fishguard". This regiment has the unique honour of being the only one in the British Army, regular or territorial, that bears the name of an engagement on British soil and it was the first battle honour (see photo at right) to be awarded to any volunteer unit.

In 1853 Lord Palmerston conferred upon the Pembroke Yeomanry the battle honour "Fishguard". This regiment has the unique honour of being the only one in the British Army, regular or territorial, that bears the name of an engagement on British soil and it was the first battle honour (see photo at right) to be awarded to any volunteer unit.

Notes:

2. A return of February 1797 gives the strength of the Fishguard Volunteers as 1 Lieut.-Col., 1 Major, 2 Captains, 4 Lieutenants, 4 Ensigns, 12 Sergeants, 12 Corporals, 8 Drummers, 4 Fifers, 235 rank and file. The Corps was composed of two Divisions, one at Fishguard, under Lieut. Col. Knox and the other at Newport, under Major Bowen.

Further Reading.

B. Fowler. The French Invasion at Fishguard. Dyfed Culture and Heritage

P. Horn. History of the French Invasion of Fishguard 1797 Pembrokeshire Press

J. Kinross. Fishguard Fiasco. The Five Arches Press

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #35

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com