- "This is not a game! This is training for war! I must

recommend it to the whole army."

THE ORIGINS OF KRIEGSSPIEL

Kriegsspiel, which is simply the German expression for 'war-game', was a name given, according to von Muffling's notice in the 'Militair Wochenblatt' (No.402, 1824), to "a number of previous attempts to represent warfare in such a way as to provide both instruction and entertainment", but was henceforth destined to refer to only one game the invention of the Regierungsrat von Reisswitz and his son Georg, a Leumant in the Guard Artillery Brigade.

After being recommended to the whole army by von Muffling, the King instructed that each regiment should be provided with Kriegsspiel equipment and the game was established as an important part of the - Prussian Army's officer training programme by Major General Wilhelm Johann von Krauseneck. New developments in weaponry and tactical doctrine were reflected in revisions of the original rules in the latter half of the nineteenth century, but the fundamental principles remained sound. Kriegsspiel assisted the General Staff to institutionalise military excellence by creating a skilled and professional officer corps, which brought the Prussian Army decisive victories in the campaigns of 1866 and 1870/1.

In 1811 Captain von Reiche of the Berlin Cadets, who was instructing Princes Wilhelm and Friedrich in the art of fortification, mentioned that a Herr von Reisswitz, a civilian, had invented a wargame in which they might be interested. The officer responsible for the Princes, Oberst von Pirch II, arranged with von Reiche for von Reisswitz to demonstrate his game. The inventor arrived with a sand table, on which hills, rivers, villages and roads were modelled to the awkward scale of 1:2373. the young princes were so impressed by the game that they wanted to play again, told their father, King Friedrich Wilhelm III, whose interest was so aroused that he wanted to see it for himself, with the result that von Reisswitz was invited to demonstrate his game to the King.

The inventor, however, explained that it would be impossible for him to transport the sand table to the court, but promised to construct a more permanent model terrain for the King, which was delivered the following year. the new terrain was comprised of small plaster squares, moulded and coloured to show hills, rivers, etcetera, about three or four inches square, designed to fit inside the open top of a large table, (von Reisswitz, it appears, had also invented wargame terrain modules!), and to be rearranged to create different landscapes. The troops were represented by porcelain playing pieces, and there were dividers for measuring distances, rulers and small boxes to place over areas so that troops who were unobserved might make surprise attacks. The rules dealt only with the movement of troops; the players had to determine the results of conflicts and losses. The game so captured the imagination of the King, the princes and their friends that it was not unusual for play to continue until after midnight!

At this time there appears to have been no idea that the game should be played for anything other than entertainment. The transition from a recreational game to a military training aid was effected by von Reisswitz's son, an artillery officer.

George von Reisswitz enlisted as a Freiwilliger (volunteer) at the age of fifteen or sixteen. he served at the siege of Glogau in 1813, was promoted to Second Lieutenant and awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class. In 1816 he was sent to 11 Artillery Brigade at Stettin, and it was while there that he began to develop his father's ideas, changing the scale to a more practical 1:8000 and calculating the results of firing by battalions and batteries. Three years later he was called to take part in the Prussian Artillery Commission and promoted to First Lieutenant in the Guard Artillery Brigade at Berlin. Here he formed a group of Kriegsspiel enthusiasts who played regularly, testing and improving the rules.

In January of February 1824, Prince Wilhelm, now Commander of the Third Army Corps and the Second Guards Division, heard of the game and asked for a demonstration. He was so impressed that he declared that he would recommend it to the King and the Chief of the General Staff.

A few days later von Reisswitz demonstrated his Kriegsspiel to the General Staff, where von Muffling was soon persuaded that it was an ideal training aid. Von Reisswitz supervised the construction of Kriegsspiel sets for the Army and revised the rules for publication. Interest in the game spread through the whole Army, but there, was a faction which opposed the game on the grounds that it would encourage subalterns to concern themselves with generalship, to the detriment of their regimental duties. Although von Reisswitz received the Order of St. John from the King in recognition of his invention, he regarded his promotion to Hauptmann in III Artillery Brigade at Torgau as banishment, became depressed and shot himself while on home leave in Breslau in 1827. His father died of grief in 1829.

Kriegsspiel, however, was sufficiently established to survive its creators and was adopted by other European armies during the nineteenth century, including those of Great Britain and the United States. All subsequent military training games have followed the basic principles of Kriegsspiel, although the umpire's role in resolving combat has recently been usurped by computers! It is still common for the hypothetical forces to be designated 'Red' and 'Blue' - just as in von Reisswitz's game.

PRINCIPLES OF KRIEGSSPIEL

Previous attempts to design military games had tended to produce derivatives of Chess, in which units manoeuvred on gridded and stylised terrain, controlled by complex rules. Von Muffling noted that such games "have usually presented many kinds of difficulties in the execution, and they have always left a large gap between the serious business of warfare and the more frivolous demands of a game". The great advantage of the new Kriegsspiel was that "anyone who understands these things which bear on leadership in battle is able to take part immediately in the game as a commander of a large or small unit, even if he has no previous knowledge of the game or has never seen it before".

Von Reisswitz's great contribution to military gaming was to adopt a 'closed' game structure to recreate the limited awareness of commanders in real war, instead of the traditional 'open' structure of competitive games such as Chess, played face to face, in which the unrestricted knowledge of the positions and status of one's own, and one's opponent's, units is permitted. this increased realism was achieved by employing an umpire to control the game, implement the players' orders and resolve combats, allowing the players to receive only such information by means of observation of troops visible to them on the ground or by messages from subordinates, upon which to make their decisions, as they would have had in the field.

In Kriegsspiel, observation of the battlefield was represented by the use of highly detailed maps and metal troop blocks portraying the infantry battalions, cavalry squadrons and artillery batteries to the same scale.

At the start of a Kriegsspiel, the umpire would give all participants the 'General Idea' or background to the scenario. This might be very simple "Blue forces have invaded Red territory. Red forces have retired behind the River Selz." for example - or more complex. Then each side would be given a 'Special Idea' or scenario and briefing for that particular game: "a detailed outline of the exact strength and position of his forces at the beginning of the game, their line of retreat, their objective, and any such information of the enemy as the umpire considers he might have in reality at this stage of the manoeuvre..."

The players would then retire to write their plans and initial orders, "in exactly the same style and spirit in which the military plan would normally be made", which they would then hand to the umpire when complete. He and his assistants would position both sides' troops on his master map, move diem'in accordance with their orders, determine when contact would be made and inform the players accordingly, continuing, however, to move the troops during the time taken for this information to reach the commanders and while they formulated new orders. Players could be summoned to the master map if necessary to view the current situation, but all troops - both their own and those of the enemy- judged to be outside their vision by the umpire would either be removed temporarily from the map, or concealed by sheets of paper.

This style of gaming compelled the players to use reconnaissance to gather intelligence something never seen, because unnecessary, in conventional face to face wargames - and created the 'fog of war' without recourse to complex rules which forbid players to react to things which they know from seeing the model troops on the table top.

Musketry, artillery fire and bayonet attacks were resolved by using proportional dice to represent the odds in favour of one side, these odds being assessed by the umpire in accordance with principles stated in the rules. From the dice the umpire could read not only the casualties inflicted, but the outcome of hand to hand combat and whether shells set buildings on fire or not.

Von Reisswitz justified the use of dice to introduce the element of chance as follows: "The officer in the field can predict with some certainty that a skillful placing of his guns will inflict great damage; that a superiority of firepower should give a good result; that more damage will be inflicted if the enemy are deployed in dense masses than if spread out, etcetera, but he can, even in these favourable circumstances, only predict a generally favourable result, and not an exact one The outcome of a fight with sword or bayonet will depend on the concentration of the mental, moral, and physical strength of the combatants. One may sense, but not know, how much of this strength is present in one's troops. It is impossible, however, to know in advance how much of it is present in the enemy. His greater strength will only be felt at the moment the fight takes place. A superiority in numbers will be the most obvious condition noticeable. Again, we must say, that if one wishes to use the apparatus seriously, to strive for a realistic and lively contest, one must put the player in a position of some uncertainty at this point, as he would in reality. For this reason the dice are again employed to reach decisions over attacks with sword and bayonet."

Since the administration of the rules was entirely in the hands of the umpire, the players could not calculate their chances of success by reference to the rules rather than military knowledge and training.

Although von Reisswitz quoted distances marched by the different arms, and fire effects per two minutes, it was not his intention that the game should proceed in rigid turns, each representing that length of real time. Instead the umpire was encouraged to advance the action rapidly to a point at which one or both players might wish to issue further orders; if they did, he was to note the time taken in reality and move the action forward again to allow for that time and the delivery of the orders by aide de camp or messenger. Should a player wish to ride in person to an endangered position to issue orders orally, the umpire would again note the time it would take to reach that position, and advance the action on the master map by that length of time before allowing the player to see it.

"It will now be clear that all time taken up in the formulation, communication, and assimilation of messages and reports can be taken into account, that surprise can really happen, and that it is important to be able to grasp the implications of a message quickly, reach a decision promptly, and communicate orders clearly and briefly."

RECREATIONAL WARGAMING AND KRIEGSSPIEL

Kriegsspiel is very different from the traditional face to face wargame played for entertainment, rather than professional instruction, which has. evolved from games such as H.G. Wells' 'Little Wars' by replacing match-stick firing toy cannon with mathematical rules to determine casualties. Computers may be beginning to spare players the brain numbing calculations required to operate many sets of wargame rules, but recreational gainers still tend to place all their miniature forces in full view on the table top, rather than to create separate displays for opposing players to show only what they would be able to see from their respective vantage points on the battlefield.

A game played with maps and troop blocks may, at first sight, appear less aesthetically pleasing than one with painted model soldiers and miniature three dimensional terrain - though the maps and troop blocks can be coloured to create a very pleasing effect, not unlike hand-coloured engraved battle maps in early eighteenth century books - but it will give participants a much greater insight into the viewpoint and problems of commanders in the field than a face to face wa-game.

Kriegsspiel was known to recreational wargamers, but rarely played outside military academies since the turn of the century. In 1983, however, Bill Leeson translated and published the original von Reisswitz rules of 1824 and has done much to restore the game's reputation amongst civilian gamers. Those who have played Kriegsspiel have found it a refreshing change from conventional wargames, and one that helps develop their command skills for other games - for example Bill and a group of regular Kriegsspiel players led the German Army to victory in a Wargame Developments' megagame of the opening days of 1914, 'Guns of August', several years ago!

Bill produces English translations of the von Reisswitz rules, later Prussian and British derivatives, supplements to the rules published by the Berlin War Game Association after von Reisswitz's death, articles from the 'Militair Wochenblatt' describing sample games and the life of the game's inventor, and everything necessary to play Kriegsspiel totally: metal troop blocks representing Prussian Brigades, equivalent to British or French Divisions - of 1813-15, an imaginary map designed specifically for Kriegsspiel by Major General Meckel in 1875 and maps to the same scale of Waterloo and Koniggratz. His most recent publication is a booklet containing twelve scenarios with Special Ideas for both Red and Blue together with ideas for solo play.

USING KRIEGSSPIEL TECHNIQUES TO CONTROL A GAME WITH MODELS

Since discovering Kriegsspiel I must confess I have little time for face to face Napoleonic games, save for a lighthearted knock-about, but I still enjoy the visual spectacle of massed ranks of figures. Here is a suggestion as to how you can combine the best of both worlds!

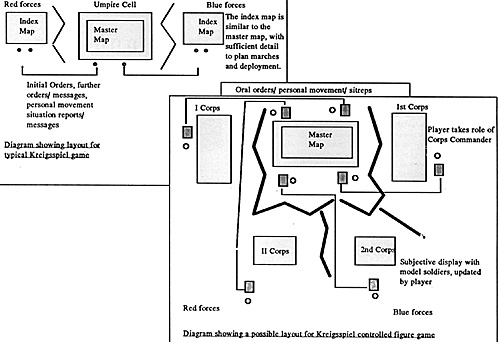

Use Kriegsspiel rules and maps to create an objective display upon which the umpire will calculate marches, casualties from musketry and artillery and resolve combats. Players will take the roles of Army or Corps commanders and will have personal displays showing their subjective perceptions of the battle, what they can see of their own forces and die enemy. The simplest and cheapest way to create such displays would be to spread cloth over assorted household implements to form the ground, use 2mm or possibly 6mm figures, lichen for woods, 'Monopoly' houses or wooden off-cuts for buildings and blue ribbon for rivers and streams.

Players will also need plenty of plain cotton wool to represent the powder smoke that would soon shroud much of the battlefield, concealing the troops from view, and some died brown to indicate dust thrown up by marching troops in the distance. Written orders will be submitted to the umpire at the start of the game. Thereafter, the umpire can either employ a team of assistants to visit each player and update the individual displays at frequent intervals, based upon what he decides the players would be able to see from their vantage points by referring to the master Kriegsspiel map; or he could use the cheap, battery operated intercoms which are available from many High Street electrical stores to communicate directly with players, giving them a verbal description of the scene and leaving it to them to update their personal displays. These briefings would replace player visits to the master map of the original game.

Since the players would not have to administer the rules, they would be free to study the action as it developed, to 'read' the battle like a real general, rather than having to concern themselves with trivial details of formation and casualties more properly the concern of a subaltern or non commissioned officer. Whenever they wished to issue further orders or send messages to subordinates, they would only have to write them down and send them in to the umpire; he would determine when or whether they were received and, if appropriate, follow them after an appropriate length of game time had elapsed. Badly written or ambiguous orders might well be misinterpreted, just as in real life, for the players would not be controlling the troops in receipt of them, as they would in a conventional game. The umpire could also place the players under some tension when within range of the enemy, by describing near misses and the deaths of staff officers accompanying them in graphic detail over then intercom!

This game structure would recreate an aspect of battle described by von Reisswitz - who, unlike the writers of present day Napoleonic wargame rules, was present at actual battles and so was able to base his rules on practical experience - but rarely reflected in modem day recreational games: "The sequence of events on the battlefield, the directions in which the troops will strike out, and the positions where actual attacks will take place, are in most cases, predetermined by the dispositions of the troops at the outset. These positions, in turn, have been arrived at by the troop movements which have themselves been influenced by the commander's understanding of the intentions and objections of the enemy - an understanding, incidentally, which may turn out to be not entirely accurate.

"In a sense, then, the commander has to leave each unit to fend for itself in the actual conflict, most of the decisions having already been made..."

I think such a game would provide a thought provoking alternative to the traditional wargame with model soldiers - why not give it a try and describe your experience afterwards in these pages.

SOURCES OF KRIEGSSPIEL APPARATUS

Several mail order suppliers stock Bill's products, but they can also be ordered directly from Bill Leeson, 5 St. Agnell's Cottages, Hemel Hempstead, Herts., HP2 7HJ.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #3

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com