Between late June and early August, Napoleon's central

army group had raced deeper and deeper into the heartland of

the Russian interior. Napoleon was desperate to out manoeuvre,

catch and then destroy the Russian First and Second Western

Armies, preferably before they were able to unite. As this

enormous body of men lunged towards Smolensk, on an ever

narrowing front, so the importance of the central army groups

northern and southern strategic flanks grew in importance. To

the North Napoleon had deployed the Franco-Swiss II Corps,

the Bavarian VI Corps and the Franco-Prussian X Corps. To the

South Napoleon deployed Dombrowski's 17th Polish Division,

Reynier's Saxon VII Corps and Schwarzenberg's Austrian

Hilfkorps. All these formations were operating, at least

originally, independently.

Between late June and early August, Napoleon's central

army group had raced deeper and deeper into the heartland of

the Russian interior. Napoleon was desperate to out manoeuvre,

catch and then destroy the Russian First and Second Western

Armies, preferably before they were able to unite. As this

enormous body of men lunged towards Smolensk, on an ever

narrowing front, so the importance of the central army groups

northern and southern strategic flanks grew in importance. To

the North Napoleon had deployed the Franco-Swiss II Corps,

the Bavarian VI Corps and the Franco-Prussian X Corps. To the

South Napoleon deployed Dombrowski's 17th Polish Division,

Reynier's Saxon VII Corps and Schwarzenberg's Austrian

Hilfkorps. All these formations were operating, at least

originally, independently.

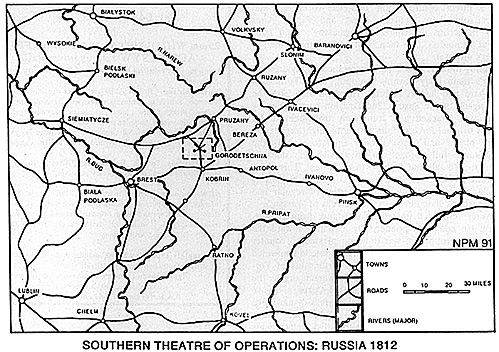

The Southern Theatre of Operations

Schwarzenberg has crossed the river Bug in early July, locating his centre of operations on the town of Pruzany. His objectives were to protect the extreme right flank of the main French thrust into Russia. As it gradually became clear, to Napoleon, that any hopes of any early success against the main Russian armies were destined to failure and frustration, his perspective of the importance of his strategic flanks also began to change. Napoleon, quite correctly, was consumed with the need to destroy the main Russian armies.

As a result, and in a bid partly to replace the already high attrition losses, Napoleon decided that Schwarzenberg's Austrian Corps was more valuable as part of the main strike force, than standing idle on his flank. Therefore, new orders were issued, and Schwarzenberg was ordered to vacate his present positions, handing over his original flank guard duties to the much smaller Saxon VII Corps. At this time, very little was known of the true strength of the Russian forces facing the Southern flank. Napoleon considered them to be no more than second line reservists with a possible strength of 10,000 men.

Even so, Reynier's strategic objectives of covering 300 miles stretching from Brest in the West to Mozyr in the East, with perhaps 17,000 men, were clearly totally impractical. To further compound Reynier's problems, Schwarzenberg had vacated his positions as soon as he received Napoleon's new orders, without awaiting Reynier's arrival. The two forces eventually met at Slonim on July 19th some 50 miles North-East of Pruzany. Reynier determined that his best option was to occupy the central position based on

Pruzany, with two relatively strong advanced flank guards in the directions of Brest and Pinsk.

The Russian Strategic Situation

Further to the South, the Third (Reserve) Russian Army commanded by Tormassov, had begun its own concentration. Tormassov had initially been directed to operate against Napoleon's strategic rear, by advancing into the very heart of the Duchy of Warsaw. However, as the two Russian main armies were forced deeper into'the heart of Russian, away from the border, Tormassov received new orders on July 17th to march North to operate against those French forces presently threatening Bagration's Second Western Army. These orders would mean a direct confrontation between Tormassov and Reynier somewhere between Brest and Pinsk. After making numerous detachments, Tormassov's main body stood at around 33,000 men, still almost twice that at Reynier's disposal.

Feinting towards Pinsk, Tormassov successfully drew off Reynier's main body towards Antopol. Then Tormassov struck hard and fast at Kobrin. There on July 27th the First Brigade of the Saxon 22nd Division commanded by Mengel was attacked and completely overwhelmed. Of Mengel's original force of four battalions, eight regimental artillery pieces and three cavalry squadrons, only the cavalry successfully broke out to survive the debacle. Reynier turned tail and fled North to Slonim. Tormassov meanwhile advanced to Pruzany and contented himself by dispatching several strong raiding parties of regular and irregular troops deep into the Grand Duchy of Warsaw.

Reynier demanded immediate assistance from Schwarzenberg. He had been ponderously marching toward the central army group, and was only too pleased to counter march to rejoin Reynier, even before Napoleon confirmed this decision. However, realising -the seriousness of Tormassov's threat, Napoleon elevated Schwarzenberg to the command of both the Hilfkorps and VII Corps, and gave him specific orders to operate against Tormassov and force him to give battle.

Tormassov had through his successive detachments reduced his available strength to around 18,000 men, whilst the combined Austro-Saxon forces now fielded perhaps 42,000 men. Tormassov learnt of Schwarzenberg's intentions during August 11th, when a series of sharp skirmishes were fought mainly between the Russians and Austrian advance guard. Tormassov drew back his forces into a strong defensive position near the village of Gorodetschna, midway between Pruzany and Kobrin. Tormassov's main line of battle was drawn up along a line of heights overlooking a marshy river line and the village of Gorodetschna.

His left flank was protected by the same river, and to his rear was a large wood, through which passed his main line of retreat, the Pruzany-Kobrin road. The river due to the swamps stretching along both its banks was only locally crossable at three points. The first crossing was adjacent to the village of Gorodetschna. The second near the village of Podoubny slightly to his left rear, and the third at the junction of the river with the wooded area in his rear. Convinced that the main line of attack would be along the Pruzany-Kobrin road, Tormassov failed almost completely to protect these latter two river crossings.

Arriving before Tormassov's position on the evening of the 11th, both Schwarzenberg and Reynier recognised the potential futility of a direct frontal assault. Reynier suggested a strong right flank envelopment, employing the two crossings to the Russian left and rear. This movement threatened to cut the Russian line of retreat, and could hopefully result in the complete destruction of Tormassov's forces. Reynier was determined to make good, for the humiliation of the Saxon Corps, following the loss of Mengel's Brigade at Kobrin. Schwarzenberg agreed, the flanking movement would start at dawn on the following day,

The Russian army counted many irregulars amongst its forces, who helped in the overthrow of the invadi*ng' forces during 1812, but perhaps few were as unexpected as those that came to Tormassov's aid during the night of August 11th-12th. A pack of wolves, obviously with an appetite for horse flesh surprised a line of tethered Austrian Hussar horses. The horses in their panic broke free and raced away through the forest into the night, vainly chased by numerous mounted and presumably dismounted Austrian Hussars. The following day the Austrian regiment still reported a dismounted troop ready for action.

The Battle

At around 5.00am on the morning of the 12th Reynier's Corps began its approach against the Russian left and rear. Schwarzenberg initially supported Reynier with Zechmeister's twelve Austrian light cavalry squadrons and Bianchi's Austrian division of eight battalions. The remaining Austrian forces remained in position facing Gorodetschna and those Russian forces deployed beyond the village. The strength of the Russian defences here meant that none of the Austrian forces were actually committed to any form of action until much later in the day. This lack of resolution on the part of the Austrians meant that the majority of the Russian forces could eventually be drawn off'to counter the as yet unrealised threat to their flank and rear. In hindsight Schwarzenberg was clearly missing a golden opportunity to successfully pin the Russian main body whilst his flank march unfolded to trap Tormassov completely.

The ground over which Reynier advanced was treacherous, numerous men of Sahr's Saxon brigade were lost up to their necks, after marching directly into a swamp. Sahr's divisional commander, Funcke, blamed this on his subordinates loss of sanity in the face of the enemy. If Sahr's orders called for him to advance, advance he would, swamp or not!

Reynier's Dispositions

A Saxon light battalion quickly seized the river crossing in front of Podoubny, but the Russians redeployed several battery of cannon to counter this threat, forcing the Saxon's back. Meanwhile, the main Saxon advance continued on further towards the Russian left rear. Reynier's force crossed the river line completely unopposed, and he continued to muster his forces within the wood out of sight of the Russians. Reynier began his full deployment at about 11.00am. From left to right his line of battle consisted of Sahr's Saxon Brigade, Lilienberg's Austrian Brigade, LeCoq's Saxon Division, and the Saxon and Austrian Light Cavalry under the orders of Zechmeister. The front extended from the river towards the vital Pruzany-Kobrin road. Tormassov's position had been completely compromised. Of those troops seconded to Reynier for the flank march one Austrian brigade remained on the far side of the river near Podoubny. This was eventually supported by a second full Austrian division commanded by Siegenthal and a further brigade of Austrian Light Cavalry.

Tormassov's Redeployment

Tormassov was completely surprised by Reynier's flanking manoeuvre, convinced that the swamp would restrict any such movement. To his credit, however, Tormassov did not panic, but calmly ordered a drastic redeployment of his main line of battle. Leaving only the Riajsk Infantry Regiment, the Tver Dragoons and six guns of Position Battery 15 to cover the Gorodetschna crossing, he redeployed his remaining forces as follows. The Vladimir Infantry Regiment was ordered to cover the Podoubny crossing as a refused right flank, supported by up to twelve pieces of artillery.

Next in line running right to left were the 28th Jager Regiment, the Tambov, Kostroma and Dnieper Infantry Regiments. Behind these, deployed in echelon to the left were Dragoon Regiments Taganrog and Starodoub. Deployed in front of the infantry was at least one further battery of artillery. All of these units were commanded by Kamenski. Markoff's forces deployed to the left of Kamenski, were deployed from right to left as follows, the Kos]6v, Nacheberg, Vitebsk, Kourin Infantry Regiments and the 10th Jager Regiment.

These infantry were supported by six cannon of Position battery 15, and four squadrons of the Tartar Uhlan Regiment which linked Markoff's command to that of Lambert. This latter generals forces, deployed from right to left, consisted of the Alexandria Hussars, and the 14th Jager Regiment, supported by six cannon. Then beyond the Pruzany-kobrin road were deployed the Pavlograd Hussars and the three irregular Cossack Pulks.

Until the full completion of Tormassov's redeployment, the initiative had clearly rested with Reynier's forces. However, Reynier appeared to lack the final commitment to push on to the kill. Perhaps he had been surprised by Tormassov's resolve to turn and fight. Perhaps he was awaiting some movement from the Austrians deployed in front of Gorodetschna. Whatever the reason, Tormassov took advantage of the slowness of the Saxons and Austrians. He determined to delay the tightening of the noose by ordering repeated spoiling attacks from his cavalry whilst maintaining a heavy artillery bombardment along his whole front. Sahr and Lilienberg's brigades both suffered heavily from these tactics.

To counter the cavalry attacks, Sahr made use of an innovative form of mixed order. He deployed two battalions of light infantry in line, each flank being anchored upon a battalion square of grenadiers. In front of this formation were deployed the skirmish companies of the light infantry regiment. Unfortunately, the deployment of these skirmishers resulted in the loss of many,brave men, who although forming hasty squares or klumpen, when threatened by cavalry, still lost heavily to the determined horsemen.

The Russians repeated their spoiling tactics against LeCoq's Saxon division on the right. However, Zechmeister 'was here ab.le to support the infantry, and successfully countered one such attack both frontally and in flank, taking a number of Russian Cossacks and regular cavalry prisoner. Following this success, Zechmeister was ordered to advance part of his cavalry to the right of the Pruzany-Kobrin road, in an attempt to outflank the Russians. Lambert was able to counter this movement with the sixteen squadrons of Hussars, that he had available, and was therefore able to keep open the vital road.

The Final Attack

Towards evening, Schwarzenberg ordered forward a final attack against the refused Russian right flank. This movement was to be supported by a general advance along the whole line with the skirmish companies of LeCoq's division. The primary attack was lead by the Austrian Colloredo-Mansfeld and Alvinzy Infantry Regiments. The former regiment was supported by the Hiller Infantry Regiment, and the latter by Sahr's Saxon brigade. The Colloredo-Mansfeld regiment swept across the river in front of Podoubny and advanced against the Russian flank.

The Russian infantry opposed to them were initially forced to withdraw. But this movement exposed the Austrians to the attentions of the Russian Dragoons, who in their turn forced the Austrians to withdraw to the river line. Meanwhile the Alvinzy regiment formed in Battalion Masse, as protection against the cavalry, advanced towards the Russian infantry. But they too failed to press home their attack and in their turn retired to their original positions.

Meanwhile, Frimont, commanding the Austrian forces facing Gorodetschna and the original Russian positions, finally put in an appearance by advancing to occupy Gorodetschna. Tormassov quickly reinforced his original position with artillery and cavalry, and so intimidated Frimont that he was entirely satisfied to remain exactly where he was huddled in and around Gorodetschna.

Conclusion

Throughout the day and although enveloped on three sides, Tormassov had successfully evaded the threat of total annihilation. Obviously his survival was in no small part due to the timidity of Schwarzenberg and those officers under his command. Gorodetschna was a brilliant exercise in marching to the flank and rear, not only for the Austro-Saxons, but similarly for the Russians.

At the same time the battle is repeatedly an example of the missed opportunity. Tormassov was outnumbered two to one, but Schwarzenberg seemed more intent on humiliating his opponent than destroying him. During the night Tormassov slipped quietly away, leaving Lambert as a rearguard. Tormassov's losses amounted to perhaps 3000 men, nearly twenty per cent of those engaged. Whilst the Austro-Saxotn losses were perhaps 2200 men, less than ten per cent of those engaged, and five per cent of those available.

Clearly Schwarzenberg had achieved a victory, but hardly the expected decisive result, and far short of the potential that had been promised, following the brilliant tactical envelopment achieved by Reynier's flank march. Tormassov continued his retreat southward, tentatively pursued by Schwarzenberg, finally halting beyond the river Styr. Here he awaited the arrival of Tshitshagov's Army of The Danube, which would eventually join him in mid October. This final acquisition of Russian strength would finally throw the balance of strength in the Southern theatre, irrevocably into the hands of the Russian army.

Napoleon heard of Schwarzenberg's victory whilst considering his own options at Smolensk, and suggested to the Austrian Emperor that Schwarzenberg should be elevated to the rank of Fieldmarshal. The Russians meanwhile, were most displeased with the Austrian's evident lack of promised restraint, and complained bitterly to Vienna. The Austrian Emperor had earlier promise the Russian court that their involvement in Napoleon campaign was to be purely token.

Perhaps this secret treaty explains, more than any other reason, the hidden purpose behind Schwarzenberg's apparent timidity during the battle. However, the result of Schwarzenberg's victory was far more to aid the Russian cause than any one might have then suspected. The news of Schwarzenberg's victory, timed to the news of Oudinot and St.Cyr's victory at Polotsk, was heavily responsible for finally convincing Napoleon to carry the central army group on beyond Smolensk.

Napoleon now felt secure, holding the advantage in both the North and South. When members of Napoleon's staff made their objections to this fateful decision, Napoleon simply replied, "the wine has been poured, it must now be drunk". The wine, however, was beginning to lose its bouquet, and during the dark days of November and December was to become completely unpalatable.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #2

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com