The Engagement at Gefrees

8 July 1809

by Jack Gill, U.S.A.

| |

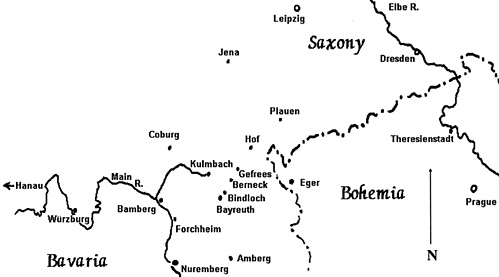

One of the least-known engagements of the 1809 campaign took place near the small town of Gefrees in north-eastern Bavaria on 8 July. Though small in scale, several noteworthy features, particularly the unusual orders of battle, make Gefrees an interesting combat. A Strategy of DiversionThe engagement at Gefrees had its origin in Archduke Charles's strategic predicament following the Battle of Aspern-Essling (21-22 May). Unable to devise a suitable offensive plan for his Main Army in the aftermath of his success, Charles began looking to peripheral theatres where operations by smaller forces might threaten Napoleon's lines of communication, distracting the Emperor and sapping French strength without placing the principal Habsburg force at risk. With Austrian designs frustrated in Poland and Italy, the only remaining venue for such diversionary action was the long Bohemian border with Germany. Moreover, to Habsburg strategists, a strike into central Germany would capitalise on the victorious progress of the renegade Prussian Major Ferdinand von Schill's raid (as reported in glowing phrases by Schill himself) and might spark anti-French uprisings throughout the Confederation of the Rhine. The forces on hand for these rather grandiose tasks, however, were small and indifferent in quality, a jumble of depot troops, Landwehr and small line formations left to guard the frontiers of Bohemia as Charles invaded Bavaria in April. By late May when Charles issued his orders, there were two small divisions capable of carrying out the diversionary offensive. Gathered around Theresienstadt, General-Major (GM) Carl Friedrich Freiherr Am Ende's command (8,600 men and 10 guns) was to push north toward Dresden in Saxony, while Feldmarschall-Leutnant (FML) Paul Radivojevich (4,400 men and 4 guns) advanced on French-administered Bayreuth from Eger. The forces available to protect Napoleon's rear area and the realms of his German allies were an equally odd admixture: French recruits and provisional units, Dutch regulars, the fresh-baked Westphalian Army under its feckless king, Saxons, Bavarians, indeed Germans of every variety, Danes, and even, for a brief time, Portuguese. Intended to counter external threats and repress unrest within Germany, most of these disparate elements were grouped under two larger formations. Napoleon's youngest brother, King Jerome of Westphalia, commanded X Corps, operating in his own kingdom and in Saxony, while stalwart old Marshal Francois Kellermann used his talents to organise a Reserve Corps centred around Hanau. PreliminariesThe Austrian invasion of Saxony opened on 10 June when Am Ende's force, including two small German free corps from Braunschweig (Brunswick) and Hesse-Kassel, crossed the border and headed north. Dresden, the Saxon capital, was duly taken, but Am Ende was a cautious, indecisive commander and his further progress toward Leipzig was slow and hesitant. Never the less, the Saxon defenders, commanded by the energetic Oberst Johann Adolf von Thielmann and reinforced by GM Ludwig von Dyherrn's command recently arrived from Poland (see Issue No. 10), were greatly outnumbered and forced to fall back before the torpid Austrian advance. Westphalia's King Jerome, however, marched to Saxony's assistance and united with Thielmann east of Leipzig on 23 June; the Saxons and Westphalians then took the offensive, pushing Am Ende back to the Bohemian border and reentering Dresden on the 30th. Meanwhile, Radivojevich had also pushed into Germany, occupying Bayreuth and throwing raiding parties out to Bamberg and Nuremberg. Napoleon, concerned for the security of his long line of communications through Bavaria, sent elements of the Reserve Corps to counter the Austrian incursion and these succeeded in forcing Radivojevich's men out of Nuremberg by the end of the month. Radivojevich retired to Bayreuth but the French continued to press him and he felt compelled to fall back to a position near Bindloch on 6 July (while the outcome of the campaign was being decided on the bloody fields around Wagram). The French force moving against Radivojevich came from two directions. General de Division (GD) Jean-Andoche Junot, who had taken Kellermann's place as commander of the Reserve Corps in late June, brought a division of fresh conscripts and 12 guns east from Hanau via Wurzburg. Arriving at Bamberg on 5 July (as the Battle of Wagram was opening), he found GD Jean Delaroche in the ancient city with two regiments of French provisional dragoons (1st and 5th), 510 Bavarian infantrymen from nearby unit depots and two captured Austrian 3-pounders manned by Bavarian gunners. Delaroche had come up from southern Bavaria in late June at the head of the 1st Provisional Dragoons. Their approach caused Radivojevich's detachment to abandon Nuremberg, and they skirmished with the retiring Austrians before proceeding north to Bamberg, picking up some Bavarian infantry reinforcements en route. Marching separately, the 5th Provisional Dragoons gathered additional Bavarian foot soldiers and the two small guns on their way to Bamberg. Although the raw dragoons were still acquainting themselves with the arts of equitation, they provided Junot with a considerable mounted force and he immediately continued his advance on the now worried Radivojevich, entering Bayreuth on 6 July as the Austrian withdrew to the east. The Austrians, however, also had a new commander, FML Michael Kienmayer. Kienmayer was a distinguished soldier who had led II Reserve Corps during the first weeks of the 1809 campaign. Appointed to command Am Ende's and Radivojevich's divisions for the incursion into Germany, he quickly brought a sense of initiative, purpose and energy into what had previously been a rather aimless enterprise. Apprehensive about the separation of his two subordinates in the face of a numerically superior enemy, he decided to exploit his central position to defeat each of the Franco-German corps in turn. The lethargic and disorganised X Corps posed no immediate danger but Junot's rapid advance threatened to overwhelm Radivojevich in Bayreuth, so Kienmayer took about half of Am Ende's troops and marched west to strike Junot. Am Ende was left to guard the passes into Bohemia while Jerome entertained himself with the occupation of Dresden. On the night of 5 July, a messenger from Radivojevich brought a plea for help to Kienmayer's headquarters in Plauen. In his reply, the Austrian commander told his nervous subordinate to hold the heights around Bindloch for as long as possible but gave him the freedom to retire to the defile at Berneck if necessary. Under no circumstances, however, was Radivojevich to withdraw beyond Gefrees. Having issued these instructions, Kienmayer set his Austrian troops on the road for Hof early on 6 July, leaving his Braunschweig and Hessian allies in Plauen. Radivojevich's situation deteriorated over the next two days as Junot's men slowly edged the Austrians back. On the afternoon of the 6th, Junot advanced out of Bayreuth, driving in Radivojevich's outposts and forcing the Austrian general to abandon the Bindloch position next morning, leaving a rear guard behind as his main body withdrew to Berneck. The French continued to press Radivojevich throughout the 7th, pushing at his rear guard and threatening to outflank his new position at Berneck via Micheldorf and Gesees. Under constant skirmishing, the outnumbered Radivojevich thus fell back on Gefrees. Having received no reply to the three urgent messages he had sent to his superior during the course of the day, Radivojevich was worried as night fell but apparently decided to hold the Gefrees position in accordance with Kienmayer's last orders. BattleThe morning of 8 July found the two little armies facing each other across the valley occupied by Gefrees. Radivojevich had posted the 1st Tabor Landwehr in the little town itself and established the bulk of his command on the slopes to the northeast to cover the two main roads (toward Hof and Eger). Detachments from the Deutsch-Banat Grenz Regiment (No. 12) guarded his right flank at Wulfersreuth and Fichtelberg (apparently two companies in each town). The French and Bavarians held the heights to the south, their right anchored at Grunstein and their left rather in the air on the Pfaffenberg (three battalions). A small detachment watched the road to Kulmbach on the far left. GD Delaroche was apparently in control of operations for most of the day, Junot having reportedly (according to German sources) repaired to Bayreuth to sample the local cuisine. The terrain between Gefrees and Berneck was characterised by low hills (most between 500 and 600 metres high) with steep, wooded slopes looming over narrow valleys formed by slender, winding streams. There were thus few places where a commander would have an unobstructed view of his entire force; although the French position south of Gefrees did afford a good field of observation, the Austrians would find it difficult to co-ordinate their various columns. Tactical manoeuvre was also restricted. The one principal road (chaussee) twisted its way from Gefrees down to Berneck and from thence on to Bindloch and Bayreuth, and numerous forest ways provided opportunities for the movement of small units, but the numerous defiles constricted formations and offered excellent rear guard positions. In general, therefore, it was a close battlefield, "coupiert" as the Germans would say, hindering movement and presenting significant challenges to Napoleonic command and control techniques. The slopes along the Olschnitz from Stein to Berneck were particularly steep, but south of Berneck the ground opened up and levelled out along the valley of the Weisser Main and Kronach stream. These charming hills and dales echoed with musketry as the skirmishers of both sides began exchanging fire in the early hours of 8 July. The opening patter of shots soon became a general crackle, but at about 10 a.m., the firing abated as the French seemed to grow more cautious, less aggressive. It is not clear what caused this change in attitude. Perhaps Junot's supposed absence inhibited Delaroche, or perhaps the French had received intelligence of Kienmayer's approach and were reluctant to commit themselves to a general engagement with an enemy that was about to be reinforced. For Kienmayer was indeed marching to support Radivojevich. Having read the latter's anxious requests for assistance, the Austrian commander had cancelled a planned flanking move via Kulmbach and directed his scattered forces to assemble at Munchberg: the Austrian troops from Helmbrechts (9 kilometres), their allies from Hof (20 kilometres). Hastening south along the main road, these reinforcements reached the battlefield at about noon, giving Kienmayer the numerical superiority he needed to assume the offensive. Kienmayer's initial plan of attack called for an advance against the French right by the Grenz companies from Wulfersreuth and Fichtelberg. These were to move directly on Bayreuth, supported by a third column advancing on Berneck through Grunstein and Stein; once these movements were underway, Radivojevich was to advance down the main road with his command and some of the other Austrian troops. The allied troops were evidently intended for the army reserve. In the event, however, the Grenz companies were slow off the mark and did not reach their objectives until the following day; their actions thus had almost no influence on the coming fight. The Braunschweig contingent, on the other hand, played a key role. As Kienmayer and Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Braunschweig rode forward to reconnoitre, the Braunschweig battery commander, Captain Korfes, noticed that the French left was in the air and dominated by a small hill. He quickly brought this fact to his duke's attention and the eager Friedrich Wilhelm received Kienmayer's permission to turn the French left flank while Radivojevich prepared to drive up the centre. The duke rode back to alert his ad hoc command (probably waiting near Lubnitz): the Braunschweig troops, III/Erbach, the Jager company, the Schwarzenberg Uhlan squadron, and the Hessian Jager company. This little force, perspiring profusely in the afternoon heat, clambered up the slopes of the hill just southwest of Witzleshofen (Berchertsberg), drove off a weak French picket and dragged up the Braunschweig artillery pieces. The guns were positioned, the infantry formed into two attack columns, and at about 2 p.m., Braunschweig ordered his men to advance against the French on the Pfaffenberg. Offering only brief resistance, the three battalions on the hill were soon retreating rapidly through Boseneck and the entire French line was unhinged. Pressed by Braunschweig on the left and Radivojevich in the centre, the French retired along the main road toward Berneck. Delaroche attempted to form a line near Lutzenreuth, but the enemy appeared on the Kesselberg before he could get his men into position and he was forced to continue his withdrawal. Although a rear guard of two battalions courageously held the defile north of Berneck for a time and halted again on the northern edge of the town to slow the pursuit, they could not stop Kienmayer's pursuit. Outflanked by Austrian and Braunschweigers advancing on Micheldorf, the French infantrymen were again compelled to withdraw. Leaving a rear guard north of the bridge over the Weisser Main, Delaroche pulled his troops back into a new position on a low rise just north of the Kronach between Neudorf and Kieselhof. It was nearly dusk when Duke Friedrich Wilhelm arrived at Micheldorf with his panting soldiers. Since dawn, his men had been marching uphill and down in the oppressive July sun and many were suffering from heat exhaustion, indeed seven reportedly succumbed to sunstroke. His command was doubtless relieved that nightfall was imminent, but Oberstlieutenant Rosner of Kienmayer's staff arrived with additional Austrian troops and wanted to probe the new French position. Rosner's force (probably the two companies of Mittrowsky and Kienmayer's Landwehr battalions) had marched south from Gefrees through Wasserknoden without encountering the enemy and he may have seen the closing hours of the day as a last opportunity to push the retreating French. He thus rode down the steep slope from Micheldorf at the head of the Schwarzenberg Uhlan squadron, forded the Weisser Main and advanced toward Neudorf. His expedition was short-lived. Taken under fire by six guns and threatened by French dragoons who suddenly appeared from the Kronach valley, Rosner and his Uhlans beat a hasty retreat back across the Weisser Main. Rosner's probe was the last act of the little engagement. Exhaustion, darkness, and a tremendous summer thunderstorm brought the fighting to a close with the two armies separated by the waters of the Weisser Main. As buckets of rain pelted down and violent winds lashed the forests, the French recovered several guns and other artillery equipment from the northern bank of the Main and withdrew to the south leaving the enervated Austrians and their allies in possession of the field. Although his losses had been small, Junot was convinced that he was badly outnumbered and he continued his retreat through the next day. That evening (9 July) found the French and Bavarians some 25 kilometres south of Bayreuth, and by the 10th, they had fallen back another 20 kilometres to Amberg. Kienmayer, having achieved his strategic objective of defeating Junot - even if the victory was more psychological than physical - turned back to the east to confront Jerome's X Corps at Hof. The Westphalian King, however, did not wait to be attacked. Accepting exaggerated estimates of Kienmayer's strength and worried by reports of domestic unrest in his realm, Jerome withdrew to the north with unseemly haste. News of the armistice signed at Znaim on 12 July brought active campaigning to a halt before Kienmayer could inflict additional embarrassment on his stumbling foes. Indeed, the campaign surrounding the Engagement at Gefrees shows Kienmayer making excellent use of a classical strategy of the central position. Caught between two forces who would outnumber him if combined, he concentrated superior forces on the battlefield and defeated the more dangerous of his adversaries before the other could arrive. He thus prevented the concentration of his opponents and maintained his own command as an active, if minor, threat to Napoleon's line of communications through Bavaria. Junot, on the other hand, while advancing from Hanau with admirable alacrity, seems to have lost his nerve upon learning of Kienmayer's approach. The reverse his green little force suffered at Gefrees was hardly debilitating, but he chose to believe the highest estimates of Kienmayer's strength and retreated to a distance that made co-operation with Jerome's corps impossible (proclaiming all the while that he was anxious to co-ordinate his manoeuvres with those of the young Bonaparte). The situation thus provides yet another example of the manifold advantages inherent in unity of command. Tactically, the two little armies performed fairly well. It is fortunate that neither had to face a division of veterans, but both the French and the Austrians conducted themselves with surprising steadiness despite their severe limitations. It is noteworthy that both commanders made repeated use of flank marches to turn their opponents out of otherwise fine defensive positions. The French commander, apparently Delaroche, did not pay enough attention to the weakness of his left and the three battalions on that flank retreated in such haste that they left their rucksacks and two ammunition wagons behind, but German and Austrian sources praise the orderliness of the retreat and the steadfastness of the rear guard. The artillery equipment left behind on the north bank of the Weisser Main, however, would seem to indicate that some of this order deteriorated when the retiring units reached the bridge over that river. Having marched hard and fought repeatedly under the blazing July sun, the Austrians and their Braunschweig allies could also be satisfied. If Kienmayer's original plan of attacking the French left was somewhat unrealistic, he quickly accepted the Braunschweig captain's proposal and Duke Friedrich Wilhelm's attack successfully dislocated the enemy's line. From the limited insights provided by Gefrees, Kienmayer showed weaknesses in movement planning and tactical control of his forces. He rushed his advance guard to Munchberg by forced marches, for example, but then required it to wait several hours for the slower Landwehr to catch up before ordering it to proceed to the battlefield. Once the engagement opened, there is little evidence to indicate that he exercised much control over the tactical employment of his corps, his subordinates seem to have made most of the battlefield decision in the absence of any broader guidance from their commander. None the less, most of those decisions were felicitous and both the Duke of Braunschweig and Major Rosner demonstrated commendable initiative during the course of the day. For the French, then, Gefrees was a regrettable reverse made much worse by the overhasty retreat afterward. For the Austrians, it was a small success, by no means decisive, but sufficient for their strategic purposes. Battle of Gefrees Order of Battle Battle of Gefrees Update (FE15)  Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #12 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 1993 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |