Simulating the cut and thrust of campaigning in the era before mass armies clogged up the map has rarely been successful. It is to this end that Martin James and I have been discussing CAMPAIGNS OF MARLBOROUGH (World Wide Wargamers - 3W, originally published in the WARGAMER magazine), although the concepts have much in common with any other period before 1914. However, attempts to theorise about warfare are always weakened where they lack a firm framework of "facts". To this end this article covers the campaign of 1708 in Flanders, in terms of the game and how it might be simulated. My source is mainly Churchill as he is both available and detailed. Whether he is accurate is a matter upon which I cannot comment. Throughout I use the map and turn concepts of CAMPAIGNS OF MARLBOROUGH, however this article is not intended to criticize that game so much as to indicate areas that a designer should seek to simulate. I assume that the aim of the game is to place the players in the same position as their historical counterparts with similar resources and aims, abilities and constraints. My comments are in italics.

Campaign Opens

The campaign opened in late May after the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene returned from meeting the Elector George of Hanover. The Allied plan, for public consumption, was for George to threaten the Rhine with Prince Eugene threatening the Moselle and the Duke of Marlborough operating in Flanders. However, the Moselle campaign was to be a feint to draw off the French under the Duke of Berwick and it was intended that Prince Eugene would then move to Flanders to give the Allies a chance of forcing battle with greater numbers. The plan was spoiled by the delay experienced by Prince Eugene in raising his army (which rather than 40,000 men ended up with only 15,000) and the fact that the Duke of Berwick was perfectly able to determine his uncle, the Duke of Marlborough's, plans and match Prince Eugene's movements with his own.

The game fails to consider the possibility of a delay in fielding an army and of reaching agreement between allies which in a pre-telephone era is even more difficult than it is now. The mysterious silence on the Rhine front thoughout the campaign s one the game is unlikely to re-create.

The French had about a 20,000 advantage (which the game neglects) but suffered from having the inexperienced Duke of Burgundy replacing the Elector of Bavaria in Flanders. The Elector went off to observe the Imperial army under George of Hanover. The French generals (the Dukes of Vendome and Burgundy) could choose to threaten Ghent in the west or Huy in the cast but the real trick (which the game neglects again) was that the "Belgians" were deeply irritated with the Dutch and were ready to admit the French to some of their cities. Bruges and Ghent were on offer and the Duke of Marlborough had had to pacify Antwerp already. If the rising came at the right time it could open up the campaign for the French and outflank the Allied gains from the Ramillies campaign.

Get your numbers right if you are to get the right feel (the French clearly are not mortally afraid of Marlborough. Most military campaigns need, and usually have, a little ginger from political or strategic events to lift them out of the rut. It is by exploitng these perceived advantages that generals seek to gain an edge. Players of THE KING'S WAR wilil recognize the Ambuscade concept here.

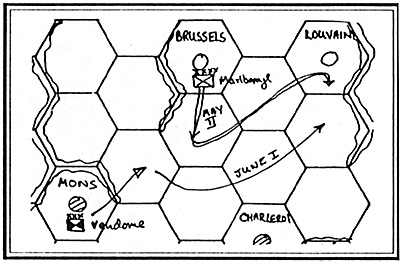

The initial moves of the campaign consisted of both sides moving in concert (see map). As

the French moved cast from Mons they were tracked in parallel by the Duke of Marlborough all

the way to Louvain. Like two martial artists cautiously side-stepping neither side had found a

weakness in the other. The Duke of Malborough was waiting for Prince Eugene and the resultant

numerical superiority, the French knew the possibility of revolt in Ghent and Bruges might offer

better pickings than an attack on a dangerous enemy. Both were content to wait (unlike gamers,

but then designers so rarely give them any reason to wait).

The initial moves of the campaign consisted of both sides moving in concert (see map). As

the French moved cast from Mons they were tracked in parallel by the Duke of Marlborough all

the way to Louvain. Like two martial artists cautiously side-stepping neither side had found a

weakness in the other. The Duke of Malborough was waiting for Prince Eugene and the resultant

numerical superiority, the French knew the possibility of revolt in Ghent and Bruges might offer

better pickings than an attack on a dangerous enemy. Both were content to wait (unlike gamers,

but then designers so rarely give them any reason to wait).

The French then changed direction heading west. A flying column under the Comte de La Motte was sent to Bruges (taking only a day to reach the city) while the rest of the French army headed for Ghent covered by a rearguard under Count Albergotti. The Duke of Marlborough responded by moving west himself but only to cover Brussels.

Why did he not attack count Albergotti or stop the French as they crossed his front

heading towards Ghent and the siege of Oudenarde? Plenty of reasons are suggested but I

favour the simplest. The Dukes of Burgundy and Vendome had stolen a march on the Allies

and the Duke of Marlborough had lost contact, until this was re-established it was very

dangerous to seek to attack what might be an entire army. The Duke of Marlborough pulled

back to a central position and guarded his main position - Brussels.

Why did he not attack count Albergotti or stop the French as they crossed his front

heading towards Ghent and the siege of Oudenarde? Plenty of reasons are suggested but I

favour the simplest. The Dukes of Burgundy and Vendome had stolen a march on the Allies

and the Duke of Marlborough had lost contact, until this was re-established it was very

dangerous to seek to attack what might be an entire army. The Duke of Marlborough pulled

back to a central position and guarded his main position - Brussels.

When two armies are in operational contact, they frequently move together until such time as one breaks contact with the other. This can be handled by having incremental movement, rather as a cavalry charge in the LA BATAILLE (Nopoleonic) series. The problem with incremental movement is that there are difficulties where more than one main force per side is involved.

Every so often, one side gets the edge and can either attack or move faster. I would see what the Duke of Vendome did as being equivalent to the end of the movement in unison with the French moving two or three hexes and the Allies not moving at all. This allowed the French the final separation. It may also be dealt with by allowing reserve movement rather than interception. That is, the non-moving units may move other than to simply move to attack the stack. It is odd that a defensive army must attack if it wishes to react when what it needs to do is be able to move, leaving the attacking to the force to which it reacted (in THE KING'S WAR I use the Break Contact concept).

Ghent and Bruges

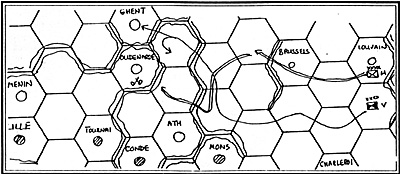

The French had now taken Ghent and Bruges. They had a supply line stretching down the rivers and canals to the coast and had opened a siege at Oudenarde. At this point the initiative passes from Vendome to Marlborough.

Although the Duke of Berwick and Prince Eugene were racing for Flanders any immediate counter-move had to come from the Duke of Marlborough and his Dutch and British troops alone. The main French army was covering Oudenarde and Ghedt behind the Dender river. The Duke of Marlborough swung south and at Lessines crossed the Dender with sufficient troops to block any interuption of the crossing of the rest of his army. Both armies now headed towards Oudenarde and the climactic battle. A description of which is not for this article.

River lines are only useful close to your mani army if the enemy is willing to march out of his way, and you do not follow him, he will eventually find a crossing point.

The Battle of Oudenarde cost the French 6,000 dead, 9,000 prisoners and 15,000 "lost." The percentage of dead or captured is only 13%. The larger figure represents troops who have exited the battle safely but not in good order. A successful pursuit might bag some of these, otherwise they would fetch up in adjacent fortresses and can be collected given time. The essence of exploiting victory is not to give them that time. The Duke of Vendome retired on Ghent while the Duke of Berwick arriving at Givet strengthened the garrisons at Tournai, Ypres and Lille from the "lost" boys.

The strategic position was unusual, for both the Allied and French armies were "cut off" from their bases. One had to winkle the other. For the rest of the campaign the French were reviled for failling to attack the Allies at numerous occasions. Yet one wonders if, after Oudenarde, it was reasonable to expect the French to recover their morale quite so quickly (one wonders if fighting battles against the Duke of Marlborough was ever reasonable!). The rule in FREDERICK THE GREAT for demoralised armies comes to mind here.

Beaten armies suffer several problems: They have lost a lot of men, more men are temporarily lost and will turn up as time goes by, and their morale and certaiinly the morale of their leaders, is shot.

The Duke of Marlborough now had the full initiative. He tried to winkle the Duke of Vendome by raiding into Artois and Picardy with cavalry. These raids also brought in vital forage. The Duke of Marlborough had for some time advocated landing on the estuary of the Somme and march on Paris by way of Abbeville. Churchill concludes these raids into Artois and Picardy indicate how successful this outflanking policy would have been. I would note that the lack of fortresses would have made depots difficult to defend for both sides but the speed of Marlborough might have overwhelmed a stunned enemy. The plan was not to be accepted by the Allies and unfortunately you cannot try it in the game either!

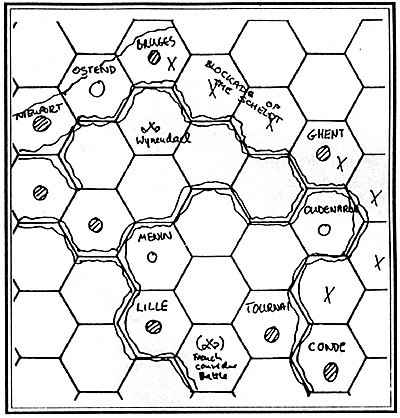

The Duke of Marlborough then concluded an attack on Lille was to be the next stage of his campaign. Lille being of great sentimental value to Louis XIV. However, the route of river transport for the Allied siege guns to Menin was interrupted by the French forces at Ghent. The Duke of Marlborough was obliged to pass his siege train from Brussels to Menin by land covering the transit with his own and Prince Eugene's armies. The French did not intervene.

Siege guns are not typically part of a field army.

The siege of Lille opened in September I (game time) of 1708 with Prince Eugene's army acting as siege army and Marlborough's as covering army. Louis XIV wished to have a battle to drive off the Allies. In obedience to his instructions the Duke of Vendome moved from Ghent to Lessines to meet the Duke of Berwick who was moving up from Mons and the combined armies progressed to Lille. Here the divided French command managed to put off combat by failing to come to a decision. (Churchill implies some cowardly froggy duplicity here). At first the Allies drew off Prince Eugene as well as the Duke to join the possible battle but following a sortie from the Duc de Boufflers and the garrison Prince Eugene returned to his siege lines the next day. The French War Minister Chamillart was sent to make the decision as to whether and how to attack and he appears to have elected to avoid combat and to oblige the retirement of the Allies by cutting off their supply lines.

It is notable that at one point Marlborough considered a surprise attack on the French despite their numerical superiority, and that while the French were preparing for battle to the south of Lille the Allies lost 3,000 men in a bloody assault on the north of the city. The Duke of Marlborough also refused for some time to entrench his forces as this would lose him his room for manoeuvre. His opportunity for a defensive battle was to be denied by Chamillart.

The effect of having to both run a siege and to defend against possible relief should never be disregarded. Assaults are much bloodier than the game allows and sallies should be simulated. The Duke's comments on entrenchments should perhaps be simulated by limiting the Combat Addition for a leader in entrenchments to, say, +2, so that it would improve the average leader but not the man of skill, whch is not always found in boardgames.

The French army withdrew to interdict the Scheidt from Bruges to Tournai thus

cutting off the Allies at Lille from Brussels. The Duke of Marlborough then drew

supply from Ostend and the English fleet. A powder convoy protected by General Webb

defeated the intercepting forces of Comte de la Motte at Wynendael in September 11.

Churchill informs us that the convoy brought in only a fortnight's powder.

The French army withdrew to interdict the Scheidt from Bruges to Tournai thus

cutting off the Allies at Lille from Brussels. The Duke of Marlborough then drew

supply from Ostend and the English fleet. A powder convoy protected by General Webb

defeated the intercepting forces of Comte de la Motte at Wynendael in September 11.

Churchill informs us that the convoy brought in only a fortnight's powder.

The French themselves ran powder into Lille on their dragoon's horses. The Duke of Vendome moved to block Ostend but withdrew when Marlborough advanced. The French then broke the dykes which cut off Ostend with flood water. The Allies were now dependent on foraging raids in Picardy to supply their food. Powder and shot were ferried in from Ostend across the inundations where both sides engaged in naval warfare in shallow draft vessels (let's see that in a game).

The city of Lille surrendered in October 11 but the citadel still held out. Losses to the Allies had been 3,600 KIA and 8,300 WIA. Most of November was spent by the French in argument. The Elector of Bavaria, who had returned from the Rhine front which was now in winter quarters tried an ambuscade on Brussels but the Duke of Marlborough had already increased the garrison and the move failed.

Marlborough then moved out with his army to "force" the Scheidt. The French withdrew rather than face the Duke of Marlborough and supply lines were reopened to Brussels. Lille surrendered in December I and the French morale was so bad that both Ghent and Bruges were abandoned soon after.

On numerous occasions Marlborough made a move to offer battle; in each case the French could, and dd, withdraw. Games which permit battles to be forced by simply up to an enemy are too laughable to be taken as smulations. Summply is a complex subject. Where constant supplies down a LOC cannot be supported, then convoys and foraging must suffce. A position easily identifiable by a general of the Middle Ages. The episode of the flooding and the galley warfare demonstrate how unusual warfare can be and how lmited the view of designers.

Back to 18th Century Military Notes & Queries No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to 18th Century Military Notes & Queries List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com