“Capt. Hamilton had not yet got over the river, when the battle began; but deserves well for his gallant conduct at Schlosser,” said Captain Symmes, “where hearing early in the afternoon that 1500 British had crossed at Lewistown, and were on the way up, to destroy the Army baggage piled at that place.” Hamilton organized the detachments there along with his own company, forming a command of approximate 150 men. Sending word to General Brown, he “instantly marched to meet the enemy, who chose to return and recross without a contest.” For his efforts he received no credit but other officers were mentioned in his stead. “He did not command the whole road on account of finding himself, while on the march, in contact with a superior in Rank.”

“Capt. Hamilton had not yet got over the river, when the battle began; but deserves well for his gallant conduct at Schlosser,” said Captain Symmes, “where hearing early in the afternoon that 1500 British had crossed at Lewistown, and were on the way up, to destroy the Army baggage piled at that place.” Hamilton organized the detachments there along with his own company, forming a command of approximate 150 men. Sending word to General Brown, he “instantly marched to meet the enemy, who chose to return and recross without a contest.” For his efforts he received no credit but other officers were mentioned in his stead. “He did not command the whole road on account of finding himself, while on the march, in contact with a superior in Rank.”

Two companies of the 1st Regiment, a scant 150 men, were now in Canada. The battalion had traveled more than 1500 miles from the banks of the Missouri River and now, had just landed as the sounds of the bloodiest battle of the war could be heard over the roar of nearby Niagara Falls. Without waiting for or receiving any orders, Lt. Col. Nicholas immediately formed the two companies into column and “marched with all possible expedition” to what was assumed to be the place of the battle. Nicholas detailed one man from each company to stay at the riverbank, guarding the men’s knapsacks that they dropped as soon as they heard the firing.

They were three miles in the rear of the contending armies and a little less than a mile short of the American encampment when the firing from General Winfield Scott’s brigade was heard. It was the time of long shadows as the sun began to set. As the men were already under arms, Nicholas gave the proper orders to march and the Regiment surged forward. Symmes remembered that they were running “at full speed as long as our breath would serve.” Arriving at the American camp, Nicholas searched for staff officers or anyone who could direct them. Unsuccessful in his efforts, Nicholas decided to march without orders, to the sounds of the guns.

The 1st Regiment departed the American camp, marching north on the Portage Road. Lt. Col. Nicholas and Lt. John Shaw, the regimental adjutant, were the only officers who were mounted. Lt. Bissell did double duty as the regimental quartermaster and as a subaltern in Symmes company.

Surgeon Mate Samuel C. Muir completed the regimental staff of four officers. Lt. Shaw recalled that the regiment “marched without music, in consequence of the lateness of the evening.”

It was twilight when they reached the field. Nicholas first halted in the road, and then, moved his two companies off the road into the fields west of the Peer home. The regiment progressed through young buckwheat and an orchard. Halting their march, Nicholas looked for General Eleazer Wheelock Ripely, from whom he expected to receive orders. Instead, Nicholas found General Winfield Scott and eventually a member of General Brown’s staff, Major McRee of the Engineers. Neither appeared to know where they could find General Ripley.

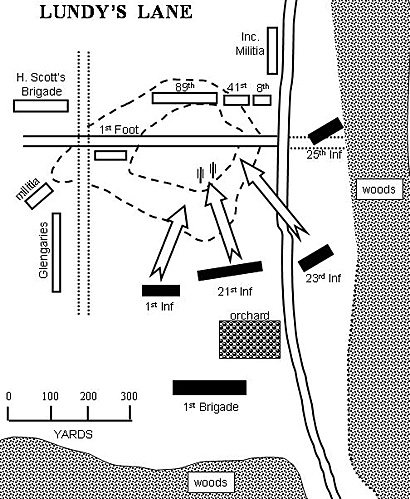

Now apprised that the 1st Infantry Regiment was in Canada and on the field of battle, General Brown issued orders for the 1st to move “to the left and form a line facing the enemy on the heights with a view to drawing off his force and attracting his attention.” Brown’s report, written in August while he was at Buffalo, stated that “…the 1st regiment…was directed to menace and amuse the infantry.” As ordered, the 1st moved forward toward the heights. The only way Nicholas had to “amuse” the British, were to allow them to shoot holes in his men with canister and solid shot.

Frontal Assault

Apparently, Brown only intended for the 1st to make a demonstration. Yet his orders sent a mere 150 men straight up the slope toward seven brass guns supported by infantry, in a frontal attack. In contrast, the 400 men of the 21st Infantry and the 300 men of 23rd Infantry were to storm the hill east of the 1st Regiment and on the British left flank and rear.

In the darkness, the British could hear the orders given to the soldiers of the 1st as they moved from column into line, and began to advance. The British gunners began an intense fire against them. Due to the slope of the hill, most of the shots soared over their heads. Lt. Col. Nicholas and Lt. John Shaw “cheered and animated the men with great effect.”

Private Patrick Gass, a 43 year old one eye Irishman, served in Symmes company. Gass had been a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and had reenlisted in 1812 at Nashville Tennessee to avoid being conscripted into General Jackson’s Militia. While marching up the hill toward the British battery, said that he felt “damned bashful” due to the bright flashes of the artillery.

The British gunners, with their infantry supports, corrected their aim and casualties began to mount. At this point, Lt. Bissell was wounded in the left leg by a “musket” ball, yet he refused to quit the field. The young quartermaster was spared a second wound when his pocket watch stopped another ball. Eventually, he would move to the rear of the regiment, to have his wounds dressed, leaving Captain Symmes alone to command the company.

Discovering that they were directly in the front of the British batteries, which began to “play very briskly” upon them, a “short retrograde” movement was made, in obedience to a distinct order from Nicholas. Nicholas had realized the folly of ordering his 150 men against the artillery and infantry support on the hill, so he gave the order for the men to “about face” and marched back down the hill. A staff officer rode up and shouted to him, “Where are you going?” Nicholas ignored him and reformed his regiment at the base of the hill. Captain Symmes remembered Lt. Col. Nicholas as “…a military character, who always inspires his troops with heroic ardor; and who dares without fear of slander to use caution where he thinks caution advisable…”

Symmes would later recall that, “The attention of the enemy was entirely directed to the 1st regiment,” when Col. Miller and the 21st made their successful attack on the battery, capturing it by a “covert” charge. “I am warranted in stating that Col. Miller did not receive a single fire from the cannon of the enemy, and I believe it to be a fact, that his attack was so sudden and unexpected, that they did not use their small arms until they were driven from their battery and forced to retreat.”

The 1st Infantry were the first to come up to support Col. Miller, advancing through a heavy fire and fell in to the left of the 21st regiment. Lt. Vasquez received a wound in the leg from a British bayonet and was also shot in the thigh. Vasquez received the dubious privilege of being the only American officer reported to have been wounded by a bayonet during the battle of Lundy’s Lane.

Sergeant Davenport of Vasquez’s company, was detailed to assist him to the rear. The sergeant laid down his musket to perform the service and when he returned, it was gone. Soon he found another by the side of a dead British soldier. Davenport took it and found it to be one of the “Glengarian muskets.” He felt it was “a very excellent exchange for the one he lost.”

Meanwhile, the British began another attack. Gass described the fierce British counterattack as a “…blast of flame and smoke, as if from the crater of hell…”

Directly to the left of the 1st Regiment, Colonel Willcock’s Canadian volunteers were posted. To their left, were Fenton’s Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers and New York militia. Willcock’s company, Fenton’s Regiment and the New York militia, were in General Porter’s Third Brigade. During the second British counterattack, the Canadian Volunteers were routed and the rest of General Porter’s Brigade followed. Lt. Col. Nicholas ordered the second company to refuse the left flank, wheeling to the left rear. They then volleyed into the British and kept up a destructive fire upon them until the counter attack collapse, and the British Infantry fell back. A Pennsylvania volunteer remembered that the 1st Regiment “repulsed the enemies’ charge when the volunteers were quite driven before it.”

The darkness contributed to many mistaken identities and soldiers from both sides were captured when they went into the enemies’ lines by mistake. Captain Symmes recalled of the 1st that, “Their cartridges were of a size…larger than the rest of the army had, this together with [our] …white pantaloons made the enemy mistake [the 1st] for a Regt. of their own and led to [the 1st] taking prisoners.” A Captain, a Lieutenant and finally two non-commissioned officers of the 89th Regiment of Foot were captured. Captain Symmes personally delivered them to General Ripley.

The soldiers were firing buck and ball, of which Symmes felt that “nothing could be better for that close night-fight.” Each man fired an average of 70 rounds during the battle. During one of the British counterattacks, Colonel Nicholas’s horse was killed by musket fire.

After the two junior officers were wounded, Captain Symmes found himself as the only platoon officer left. He personally distributed flints and ammunition to the men. The surgeon mate, Doctor Muir, who had accompanied the regiment into battle, busied himself collecting the wounded and putting them into wagons.

When the third British attack came, the 1st Regiment charged the 89th and “drove them some distance with the points of our close pursuing Bayonets, at a full charge in which they were the principal suffers.” At least three times the British had charged with the bayonet, but “their desperate courage did not serve to intimidate our soldiers who seemed resolved to perish to a man rather than retreat.”

Despite the fact that the rank and file had just completed a long fatiguing journey without an hour rest, the officers “could hardly restrain the enthusiasm of our men or call them off.”

Since the regiment had never been issued canteens, they suffered for want of water along with the rest of the American Army. Lieutenant Bissell wrote that, “about midnight we were in possession of the field when we were ordered back to camp for refreshments and a little repose,” expecting to again occupy the field at daylight the next morning.

"On the Canada Line” The Story of the 1st United States Infantry at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, July 25th 1814

Back to Table of Contents -- War of 1812 #4

Back to War of 1812 List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Rich Barbuto.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com