The Preliminaries

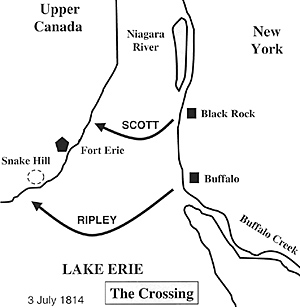

The main American offensive for 1814 was made across the Niagara River which separates New York from Upper Canada. Brigadier General Winfield Scott, commanding a brigade at Buffalo, had spent the last couple of months intensely training his men to stand up to British regulars in an open firefight. Meanwhile, his superior, Major General Jacob Brown, was gathering additional forces, collecting intelligence, and making certain that the premier naval base at Sackett’s Harbor remained secure. Finally, in the very early hours of 3 July, 1814, Brown’s Left Division made its move. [The Ninth Military District’s Right Division, commanded by Major General George Izard, was then located on Lake Champlain.]

The Left Division crossed into Canada by two routes. Winfield Scott’s Brigade crossed the Niagara and landed north of Fort Erie, the first objective. Brigadier General Eleazar Ripley’s Second Brigade was ferried across Lake Erie by schooners and small craft to land southwest of Fort Erie. The two brigades moved to link up and cut off the small British post. Major Thomas Buck commanded the 137 British defenders. He judged that his men and his three cannon were no match for the growing force materializing before his walls. Buck fired a volley of shrapnel that exploded over the regimental color guard of the 25th Infantry, wounding four Americans. Having paid his dues to the honor of his Army, Buck surrendered the fort and his men.

The Left Division crossed into Canada by two routes. Winfield Scott’s Brigade crossed the Niagara and landed north of Fort Erie, the first objective. Brigadier General Eleazar Ripley’s Second Brigade was ferried across Lake Erie by schooners and small craft to land southwest of Fort Erie. The two brigades moved to link up and cut off the small British post. Major Thomas Buck commanded the 137 British defenders. He judged that his men and his three cannon were no match for the growing force materializing before his walls. Buck fired a volley of shrapnel that exploded over the regimental color guard of the 25th Infantry, wounding four Americans. Having paid his dues to the honor of his Army, Buck surrendered the fort and his men.

That evening, more and more Americans, their cannon, horses, and wagons, were ferried across the Niagara River. Last to come across was New York Militia Brigadier General Peter B. Porter, former congressman and resident of the Buffalo area. Porter’s Third Brigade was made up of Seneca Indians, a regiment of Pennsylvania volunteers, and a company of mounted New York rifle volunteers.

On the morning of the 4th of July, Brown sent Scott’s Brigade augmented by Nathan Towson’s artillery company and Harris’s company of regular dragoons, to move quickly north and seize the bridge over the Chippawa River. The Chippawa was unfordable near the Niagara River and was the most serious impediment to Brown’s planned offensive north to Fort George, thirty-seven miles down river. Scott’s reinforced brigade moved northward along the rough road which hugged the west bank of the Niagara. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Pearson, commanding at Chippawa, sent word to Major General Phineas Riall at Fort George that the Americans had landed and were coming north. Then Pearson gathered up some dragoons, militiamen, some Iroquois from the Grand River, and the flank companies of the 100th Foot and headed south to size up the American force and delay them if he could. Meanwhile, General Riall sent for the 8th Foot at York and waited their arrival to offer battle.

Pearson’s men did what they could to destroy bridges over the few creeks but Scott’s advance was relentless. At Black Creek, an American company from the 9th Infantry was isolated on the wrong side of the river. Attacked by a troop of the 19th Light Dragoons charging toward them, the American infantry fell back to a farmhouse and fought off their assailants. After this near tragedy, Scott finally got his brigade to the area immediately south of the Chippawa River and paused. The British had a sizeable tete-de-pont defense protecting the southern side of the Chippawa bridge and earthworks and block houses north of the river. Clearly, Scott was not strong enough to assault the formidable defense which was manned by the 2nd Lincoln militia. He ordered his men to move south of Street’s Creek and open a bivouac. Near midnight Brown arrived with Ripley’s Brigade and other bits and pieces. Porter kept pushing his brigade and got them across the Niagara in the darkness. Rain began to fall making everyone a little bit miserable.

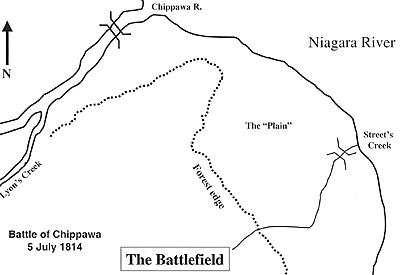

The Battlefield

The Battlefield

The Battle of Chippawa was fought on 5 July on the flat ground between the Chippawa River and Street’s Creek. The shore of the Niagara describes a gentle arc, almost two miles long between the two lesser streams. The open field nearest the river was covered in tall grass and cut by several rail fences. About three-quarters of a mile west of the Niagara lay a primeval forest, dense and covered with fallen trees. A feature which was key to the conduct of the fight was a tongue of this forest which extended within a quarter mile of the Niagara River. These woods blocked the view between the bridge over the Chippawa and the bridge across Street’s Creek. The narrow gap between the tongue of woods and the Niagara formed a natural defile in the otherwise open ground. The British would have to traverse the defile to get at the Americans and vice versa. Riall’s British, Canadian, and Indian force was safe behind their defenses along the Chippawa, unless, of course, they decided to attack.

And that was precisely General Riall’s intention. Unaware that Major Buck had surrendered Fort Erie, Riall believed that he was confronted with only a portion of the American force which he estimated at approximately 2,000. Based upon the 1813 battles, he expected the American units to be brittle, to fall apart if struck solidly even by a smaller force. Riall moved several hundred western Indians into the forest to fire upon the American camp from the cover of the forest. When the 8th Foot entered camp, tired from their long march from Fort George, he gave them a few hours to rest while he completed plans for his attack.

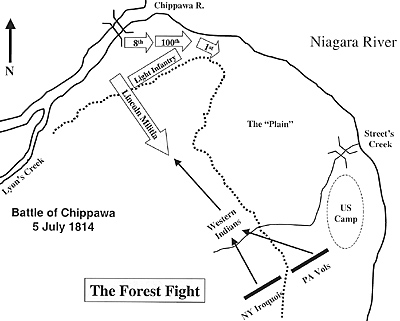

The Forest Fight

The Forest Fight

The western Indian allies of the British did their job well. They fired at the camp, proving to be a nuisance more than a threat. However, they did overrun an American piquet of a couple dozen soldiers who fled without offering resistance. Brown had had enough. He found Porter’s Third Brigade enroute to the American camp and ordered Porter to use his Seneca Indians to scour the woods of natives, thus securing the forest for any move the Americans would make the following day to get around the British camp.

The Seneca were anxious to fight but porter had to do some persuading to get even three hundred of the five hundred Pennsylvanians to join the operation. Porter formed his men in one long rank, one person deep, with Seneca on the left (in the forest) and Pennsylvanians on the right (in the open). The troops were close enough to hold hands. The formation was wide enough to ensure that no western Indians could remain unseen as the Third Brigade passed. Porter himself and his staff were in the middle of the line, between the Seneca and Pennsylvanians. The Seneca sent their war chiefs forward of the line and their scouts further ahead still.

Porter’s force moved slowly through the undergrowth and fields and stopped when the scouts located the western Indians along the thickets lining Street's Creek. After giving orders for the assault, the mixed line of Seneca and volunteers moved forward, bowling over the western Indians. The line broke up into small penny packets of Indians and volunteers as it continued relentlessly through the dark, dense forest. As the Seneca and Pennsylvanians approached the northern edge of the forest, they came upon 110 men of the Second Lincoln militia. After two years of warfare along the Niagara, the Lincoln militia were not inexperienced fighters but they could hardly resist the fierce Seneca. The New York Seneca pushed through the Lincolns and emerged from the northern edge of the forest. There they were met by the controlled volleys from three companies of light infantry. This was too much for the Seneca who fled back the way they came. Porter and some Pennsylvanians, who had been lagging behind the Seneca, made it to the edge of the woods where they too came under intense fire. Porter’s Brigade disintegrated and fell back all the way to their starting point.

The physical results of the forest fight did not match the casualty list. At least eighty-seven western Indians and eighteen Lincoln militiamen were dead. Only twelve Americans were killed in action. Nonetheless, when the fight was over, the British, Canadians, and their Indian allies remained in the forest while Porter was completely occupied in rallying and reforming his shattered brigade.

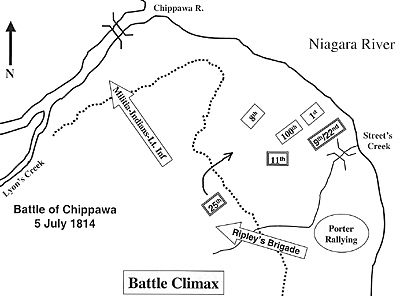

The Battle on the Plain

While the British light Infantry were driving off the Seneca and Pennsylvanians, Riall had three battalions of infantry and two artillery companies moving through the defile between the forest and the Niagara. Once clear of the defile, Riall moved further south. He formed his brigade on line. From left to right he positioned an artillery company on the river road. To its right was the Royal Scots, then the 100th Foot, and finally another battery of light guns. To the rear and in reserve was the 8th Foot.

After General Brown sent Porter’s Brigade into the forest, he noticed a cloud of dust rising in the vicinity of the defile. He immediately and correctly surmised that it was a British force moving on his camp. Brown found Winfield Scott and ordered him to move his brigade out of camp and across Street’s Creek, and there to give battle to the oncoming British. Brown then left Scott and headed toward Eleazar Ripley’s tent to get his Second Brigade into motion as well. Scott had already formed up his men with the intention of drilling them on the Plain so he moved immediately, along with Nathan Towson’s artillery company of two guns and a howitzer.

Towson crossed the bridge over street’s Creek and formed up between the road and the river. He opened fire on the heavier British guns while three battalions of American infantry crossed the bridge and peeled off to the left forming line. Riall noticed the gray jackets of Scott’s infantry and believing this to be the uniform of New York militia, believed that he was heading toward an easy victory. Scott saw Porter’s Indians and volunteers falling back on the west side of the open meadow and sent Thomas Jesup’s 25th Infantry into the woods to secure the left flank of the brigade. Last to arrive was another artillery company of light guns which Scott positioned between Jesup’s men in the woods and his other two battalions.

The Plain was about 1300 yards wide at the point of battle and therefore each side had plenty of room to maneuver. Both sides were amazingly well matched in numbers and in training. A well-aimed British ball dismounted one of Towson’s guns early in the fight. There was a narrow gap between the two leading British battalions and a larger gap between the two American battalions. Sensing that some good might come from this situation, Scott ordered the gap increased further still and the left battalion to throw forward its left flank. The result was that the British were now advancing into a funnel as the firefight began.

The Plain was about 1300 yards wide at the point of battle and therefore each side had plenty of room to maneuver. Both sides were amazingly well matched in numbers and in training. A well-aimed British ball dismounted one of Towson’s guns early in the fight. There was a narrow gap between the two leading British battalions and a larger gap between the two American battalions. Sensing that some good might come from this situation, Scott ordered the gap increased further still and the left battalion to throw forward its left flank. The result was that the British were now advancing into a funnel as the firefight began.

It’s hard to say what effect Winfield Scott’s last minute maneuver had on the outcome of the battle other than to bring the right flank of 100th Foot into a fairly intense hail of musket ball and buck shot mixed in a one to three ratio. Meanwhile, in the forest, Jesup’s battalion threw back the outnumbered light infantry, wheeled to the left, and came out of the wood line heading on a collision course with the flank of the British line. Riall tried to bring the 8th Foot into the battle but before he could do so, the weight of American fire had stopped his attack cold. With two battalion commanders and numerous other officers and scores of infantrymen down, the British faltered and then fell back.

The Battle of Chippawa was all but over. Riall managed against the odds to withdraw his beaten troops back through the defile and across the bridge while the Americans were apparently too stunned and exhilarated to conduct an immediate pursuit. Tearing up the flooring of the bridge, the British ensured that the Americans could not follow them across the wide Chippawa River. Meanwhile, Ripley’s Brigade which Jacob Brown had ordered into the forest in an attempt to outflank the British, caught up with the action too late to influence the outcome. The Americans had won a momentous yet limited victory.

The Aftermath

The British were clearly surprised that the Americans had maneuvered and fought as well as they did. Riall came out from behind his strong river line defense because he expected the Americans to buckle as they had on previous battlefields. He would not make that mistake again. Riall’s attack plan “Hi Diddle Diddle, Right Up the Middle” was not particularly imaginative. A victory on the Plain would only force the Americans behind Street’s Creek. Riall might have moved his brigade through the forest in an attempt to encircle and destroy the Americans. Riall’s greatest success was in withdrawing his brigade intact. The Americans would rue the day they let these three battalions get away.

Jacob Brown was certainly correct in accepting battle in the open. It was better than trying to pry the British out from behind their strong Chippawa River defenses. There is still some question as to Brown’s handling of Ripley’s Brigade however. It can not be established with certainty how soon into the battle Brown ordered Ripley to attempt to outflank the British by moving through the forest. In any event, Ripley played no decisive roll. Also, Brown got only two of his four artillery companies into the fight and there seems to be no obvious reason for this lapse.

Porter did well considering that his volunteers and Seneca had not trained together. He chose a formation designed to clear out a handful of Indians, not to confront formed companies of regulars. Once his Brigade was fired upon by the light infantry, Porter found it impossible to rally his men, scattered as they were throughout the forest and fleeing for their lives.

Scott maneuvered and fought his well-trained brigade with precision. The only criticism which sticks is that he failed to push hard against the withdrawing British, perhaps turning their disorderly movement into panic and rout. Nonetheless, Scott emerges as the American hero of Chippawa and his brigade earned the laurels of this sweet victory.

The grim reaper’s toll was prodigious. The Americans suffered a total of 325 casualties. In Scott’s Brigade, every fifth soldier was dead or too seriously wounded to fight. Riall lost between 485 and 515. Hardest hit was the 100th Foot with 45% casualties. Riall sent an officer under a flag of truce to ask to recover their dead from the battlefield now in American hands. Jacob Brown reportedly responded “Tell General Riall that I can bury all the men I can kill.” It was now clear that a new American army was emerging from two years of disaster and failure. The rest of the campaign was to be every bit as intense as this opening battle.

More Featured Battle: Chippawa 1814

- The Battle of Chippawa

Brown’s Official Chippawa Report

Riall’s Official Chippawa Report

Porter’s Statement

Wargaming the Battle of the Chippawa

Back to Table of Contents -- War of 1812 #3

Back to War of 1812 List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Rich Barbuto.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com