During the American Civil War, the business of blockade-running brought vast profits to British shipping firms, as well as vital goods and munitions for the Confederate war effort. For example, one ton of coffee bought for $249 in the West Indies, would sell for up to $5,500. Until the end of 1864, blockade runners had smuggled $200,000,000 worth of merchandise into a beleaguered South.

During the early years of the war, it was comparatively easy to elude the United States Navy. But, as the conflict persisted, it became harder and harder to avoid capture. By the end of 1864, territorial gains by the Federals and a huge increase in Federal warships, left only one large port open to the Confederacy: Wilmington, North Carolina.

Confederate countermeasures in defense of their harbors had, like the U.S. Navy, grown apace with the war. At Wilmington, these had developed into a complete coastal defense system, the crowning glory of which was the massive earthwork, Fort Fisher. Improved for years by its garrison and slave labor, the fort dominated the entrance to the Cape Fear River and the town of Wilmington.

Fort Fisher

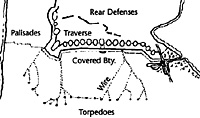

Along the outer wall stood a palisade of nine-foot high pine logs and a clear field of fire gave the defenders an edge on any attackers. This edge was further sharpened by a sally-port which would allow field guns to enfilade invaders. The fort's gate, which lay behind a swamp, was also protected by a fence and field guns. Should all this fail to deter attackers, the Rebels would blow up the very ground across which an assault would have to come. Twenty-four metal "torpedoes" were buried in the sandy approaches to the landface wall ready to be set off by an electric charge.

A massive earthwork called the Northeast Bastion connected the landface with the seaface, from where the fortifications snaked south towards the crowning glory of Fort Fisher, the Mound Battery. This stronghold towered sixty feet above sea level in order to deliver plunging fire on any warships foolish enough to try to force an entry into the Cape Fear. Among the twenty-four heavy guns marshalled along the seaface was a mighty 150 pound Armstrong-rifled cannon.

Although it was accepted that the fort would not be attacked from the rear, Colonel Lamb, its commander, ordered a series of ditches and rifle pits built to face the river enclosing

the barracks and magazines. In order to give even more security to the rear, the Rebels completed Battery Buchanan, manned by the Confederate Navy and housing four heavy guns. This bulwark was also made of Southern soil.

Impressive though all these preparations were, the stout walls and menacing gun barrels hid serious deficiencies in the Rebel defenses. Only some 600 men were available to man the bulwarks and ammunition was seriously limited. The vaunted Armstrong rifle had only thirteen rounds to beat off an attack.

The First Attack

At 1:46 pm on Christmas Eve, 1865, a decrepit old vessel named The Louisiana blew off Fort Fisher in a tremendous explosion, which reverberated along the coast and as far as Wilmington. The brainchild of controversial Union General Benjamin Butler, the eruption was supposed to destroy the fort without a full scale assault and its attendant loss of life. Two hundred tons of powder had been packed into the vessel and although the blast was awesome, it made absolutely no impact on the Confederate bastion. Matters were made worse by the fact that the navy had exploded the boat before General Butler arrived with the army transports. This action put the final touch to a long-running feud between Butler and the navy commander, Admiral David Porter. They would have no personal contact for the remainder of the campaign.

Porter led fifty-six ships with a total of armament of 619 cannon, at 12:30 pm on December 24th. These guns began their task of reducing Fort Fisher to rubble. The bombardment was recommenced at daylight on Christmas Day, as the army began its invasion. The Federals met no resistance on landing and quickly moved to capture Battery Anderson, a minor earthwork on their route towards Fort Fisher. Incredibly, some troops managed to crawl right up to the palisade without being challenged. One man even dashed to the foot of the wall in order to scoop up the fort's standard, which had been shot down by the naval gunnery.

The officer in charge believed that at that moment the fort could have been taken by fifty men and sent repeated pleas for reinforcements. Fort Fisher's menacing bulk and fearsome reputation cowed Butler into believing that it could not be taken. With a report of bad weather on the way, he ordered the landings halted and the men returned to their transports. A substantial number of soldiers were left on the beach until conditions improved enough to evacuate them. By noon on December 27th, the threat to Fort Fisher had disappeared.

Although the invasion was over, the Rebels had no cause to feel complacent. The whole affair had been seriously mismanaged and only Butler's timidness saved the stronghold. General Braxton Bragg, the department commander in Wilmington, had failed to reinforce the fort and even worse, had kept a veteran division of 6,000 men which, if released, could have easily thrown the Federals back into the sea. As Butler had been frightened off by the fort, Bragg allowed himself to be terrified by the awesome firepower of Porter's fleet, subsequently keeping his troop out of harm's way.

The Second Attack

Terry quickly moved across the neck of the peninsula. Several Confederate skirmishers were captured and the Union general was appraised of the fact that a Rebel infantry division was nearby. With this in mind, Terry ordered his men to dig in against any threat to their rear. Hindsight would show that the Federals had nothing to fear from this direction as once again, Bragg refused to commit Hoke's division, despite repeated and increasingly irreverent requests from General Whiting inside Fort Fisher.

For the time being, however, the naval gunnery was proving deadly accurate as one by one, the fort's guns were dismounted or destroyed. The surrounding palisade was also a prime target and large gaps began appearing, through which attackers could reach the walls.

By Saturday afternoon, the 14th, the Federals were well organized ashore and began making preparations for an assault on Sunday. By Saturday evening, only three heavy cannon defended Fort Fisher's landface. Over two hundred men had become casualties, leaving a meagre 1,300 men to man the remaining artillery and ramparts.

As Union troops burrowed ever closer to the earthen walls, inter-service rivalry produced a plan by the navy to put a "Naval Brigade" of 2,000 men ashore to take part in capturing the greatest fortress in the Western Hemisphere. Four hundred marines with repeating rifles would support 1,600 bluejackets armed only with pistols and cutlasses; the navy was to receive a sharp lesson in modern warfare at Fort Fisher.

At 11:30 am on Sunday, the final hail of shot and shell before the final Federal ground attack, commenced to fall on the battered bulwarks of the Rebel Gibraltar. By the time the assault troops charged towards the towering walls, only one 10-inch Columbiad remained ready for use on the landface. At 3:25 pm, the fleet shifted its concentration from the landface to the seaface to safeguard the assault troops. The sailors were the first to move out and bravely headed straight for the huge Northeast Bastion. It was here that the Rebels had marshalled the largest number of defenders and it was here that the navy's innocence received a bloody repulse. Waiting until the last minute, the garrison unleashed a withering fire, which stopped the sailors in their tracks. In their eagerness to be first atop the works, most of the officers had raced to the fore and consequently died in large numbers. Left leaderless on the open beach, the bluejackets attempted to dig themselves into the sand, but the firestorm from the fort proved too much to bear and soon shouts of retreat turned into a mad rush for the rear. The navy would have to leave it to the professionals to take Fort Fisher.

The navy's sacrifice had not been entirely for naught. At the opposite end of the landface, while most of the garrison were involved in repulsing the Naval Brigade, the army had managed to breach the gate and overwhelm the most western position, Shepherd's Battery. The fighting here was savage in the extreme as the meagre defenders attempted to close off the penetration. Lamb and Whiting rushed men from the Northeast Bastion, manned the rearward facing rifle pits, and ordered any available artillery to turn and face the new threat. As the Yankee attack stalled and no attempt was being made by the Confederates to attack his rear, Terry flung fresh brigades into the maelstrom at the western edge of the fort.

Although Bragg would not attack, he did consent to releasing a brigade on Sunday to reinforce the garrison. Unfortunately, this force was hounded by bad luck and reluctance on the part of the sailors to go anywhere near the action. Only one steamer landed its cargo and did so only after its crew was threatened at bayonet point.

Back at the earthworks, the only way forward for the Federals was to move along the landface, assaulting each traverse in line. These mounds were the scenes of some of the most bitter fighting between the North and South. The green Confederates, led by the courageous example of their officers, performed better than anyone had the right to expect. After two hours of desperate fighting, Terry ordered the fleet to again target the landface, in order to loosen the Rebel grip on the traverses. The Confederates countered with fire from Battery Buchanan which hit friend and foe alike.

The end came as Federal troops marched along between the palisade and the protection of the main walls, outflanking the defenders and rendering the rifle pits untenable. In the gathering darkness, the remaining Rebels withdrew down the peninsula to Battery Buchanan, carrying their wounded leaders. As they came abreast of the strongpoint, they found it abandoned and its artillery spiked. Battery Buchanan had ceased firing into the masses of Federals along the landface wall and it had been presumed that its guns had been silenced by the U.S. bombardment. Instead, it transpired that the officers were intoxicated and had decided to catch the last boats across Cape Fear to safety. Stranded, tired and hungry, the garrison of Fort Fisher awaited the arrival of the victors.

The horror of Fort Fisher did not end with its capture. The next morning, as exhausted Union soldiers lay scattered around the fort's interior in deep sleep, others were intent on ransacking the bombproofs for loot. Like a scene from a bad movie, torches were carried into the vast underground magazine and predictably, the forecourt was devastated by an enormous explosion. A further 265 men were killed in the accident, bringing the Union total for both actions to between 1,200 and 1,700. The Confederates lost 2,300 men killed, wounded and captured throughout the campaign.

Order of Battle and Scenario Information

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. The fort lay at the end of a sandy peninsula and was L-shaped, with the short side facing north to prevent the longer seaface from being outflanked by an invasion force. The landface batteries held twenty seacoast guns supported by three mortars and four field pieces. Between each battery was a mound of earth thirty feet high and twenty-five feet thick. The protection offered by these "traverses" was further enhanced by "bombproofs" - underground bunkers for the crew of each gun.

The fort lay at the end of a sandy peninsula and was L-shaped, with the short side facing north to prevent the longer seaface from being outflanked by an invasion force. The landface batteries held twenty seacoast guns supported by three mortars and four field pieces. Between each battery was a mound of earth thirty feet high and twenty-five feet thick. The protection offered by these "traverses" was further enhanced by "bombproofs" - underground bunkers for the crew of each gun.

On January 12th, 1865, the Yankees were back. This time Porter had fifty-nine ships with 627 guns and the army had a new leader who did get on with Porter, Major General Alfred Terry. At 7:19 am on the 13th, the navy began a bombardment to clear the landing beach. A little later at 8:30 am, the main weight of the armada began to fall once again on the defenders of Fort Fisher. The landing was a success and by 3:00 am, 8,000 men were ashore and ready to sever the fort's land communications with Wilmington.

On January 12th, 1865, the Yankees were back. This time Porter had fifty-nine ships with 627 guns and the army had a new leader who did get on with Porter, Major General Alfred Terry. At 7:19 am on the 13th, the navy began a bombardment to clear the landing beach. A little later at 8:30 am, the main weight of the armada began to fall once again on the defenders of Fort Fisher. The landing was a success and by 3:00 am, 8,000 men were ashore and ready to sever the fort's land communications with Wilmington.

Back to The Zouave Vol VIII No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to The Zouave List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 The American Civil War Society

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com