Braxton Bragg's army was in an insecure situation. He'd just had a few of his divisions transferred to the Vicksburg front and needed some time to move his army southward to a more easily defended area.

Braxton Bragg's army was in an insecure situation. He'd just had a few of his divisions transferred to the Vicksburg front and needed some time to move his army southward to a more easily defended area.

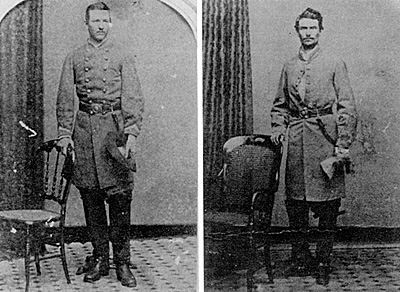

The photo on the left is of Lt. Philip B. Jones, Adjutant of the 10th Kentucky Cavalry. Jones was captured twice, the second time being on the great raid at Cheshire, Ohio. The photo on the right is of Lt. Thomas H. Wells of the 7th Kentucky Cavalry. He was also captured at Cheshire, Ohio. Both images are courtesy of the John Sickles Collection.

Bragg sent for cavalry general John Hunt Morgan and instructed him to conduct a raid against Louisville to relieve the pressure on him and facilitate his withdrawal. Morgan's intentions, however, were much more grandiose than Bragg's, and they are the basis for this narrative.

General Morgan had commanded a militia company in his native Lexington, Kentucky upon the outset of the war. He'd served in the Mexican War as a Captain of volunteer cavalry, but he didn't commit himself to the Confederate cause until his wife died in late 1861. He then took the nucleus of his militia company and rode south to seek his fortune with the Confederacy.

Morgan was a man in his late thirties, relatively wealthy, and about six feet in stature. He was strong on romance and sentiment but as a leader he was lax on discipline. His brother-in-law, Colonel Basil Duke said, "He was sensitive to everything he regarded as an obligation of honor or friendship." Like most Kentuckians from the blue grass area he was an authority on horseflesh.

With success in the saddle, Morgan's Squadron grew. Soon he was promoted to Colonel and leading independent raids far behind enemy lines. As a tactician his methods were brilliant. His Kentuckians fought dismounted primarily, where they could maneuver with more certainty and celerity. Fighting Union cavalry led by West Pointers using outmoded ideas, his men invariably inflicted more casualties than they sustained. Often it was the little things that made the difference. For instance, most cavalry regiments had every fourth man staying behind to hold the horses when fighting dismounted, and Morgan's men were no exception. But whereas in Union regiments this fourth man was usually the poorest trooper, in Morgan's Squadron he was the best. Fighting in the hilly woodlands of Tennessee and Kentucky called for a special type of warfare, and when a horse was needed, like a tourniquet, it was needed badly; Morgan's horseholders were there when the time was right.

Typical equipment for a trooper in Morgan's command was spartan. He only needed a horse, a saddle, spurs, a blanket, an oilcloth, a brace of pistols and a sawed-off Enfield rifle. Later on some guns, small mountain howitzers, were attached to Morgan's unit and were ideally suited for his purposes. 1862 was a banner year for Morgan. He fell in love with a southern belle named Martha Ready, whom he married late in the year in a gala celebration attended by President Jefferson Davis and officiated by Bishop Leonidas Polk, who doubled as a Confederate General. This was also the year Morgan began using a telegrapher named Ellsworth who carried a key with him and would shimmy up the nearest pole to tap into Federal telegraph lines, thus ascertaining the enemy's plans. "Lightning" as he came to be nicknamed, was also adept at imitating other operators and would often send confusing messages to the Yankees. Probably the most important event of 1862 to John Hunt Morgan was the Confederate thrust deep into Kentucky. Morgan and his men rode through their hometowns and were greeted as conquering heroes. Thousands of proConfederate Kentuckians flocked to join his command. David Chenault, a Madison County farmer, held a barbeque and recruited an entire regiment in one day! This was also the summer that Morgan was given a spectacular horse named "Glencoe".

Like "Robin Hoods"

A Kentucky girl spying a troop of Morgan's men camped in the woods under the moonlight likened them to "Robin Hoods". What an impressive sight they must have presented astride their sleek chargers. It was all so romantic. When the Confederates finally retreated back into Tennessee in late 1862, Morgan was riding at the head of a magnificent cavalry division.

Perhaps Morgan was incensed by Grierson's raid through Mississippi. Perhaps he thought that there were thousands of southern sympathizers in the north just waiting for someone like himself to deliver them to the Confederate cause. Maybe he was just simply fed up with all the fighting on southern soil and wanted to carry the war northward. Regardless of Morgan's reasoning, he began his great raid in the summer of 1863. He had prepared well. He even had spies in the north finding likely fords over the Ohio River, for without an escape route his raiding force could easily be trapped and destroyed. On July third they crossed the Cumberland River by lashing fence rails to canoes. Opposition was light and the division rode into Columbus at three A.M. the next morning.

When they tried to cross the bridge over the Green River they found it guarded by troops that were heavily dug in. Morgan unlimbered a gun and sent a shell into the barricade. Next he sent in a request for the Yankees to surrender. The Union commander, reasoning that since it was the fourth of July, declined Morgan's demand. David Chenault's 11th Kentucky was selected to charge the works. Chenault, brave to the point of rashness, was gunned down on top of the enemy works, pistols blazing, still urging his troops forward. After two more attacks and 71 casualties, Morgan also agreed with his northern adversary and turned his division north through Campbellsville toward Lebanon.

At Lebanon they once again faced stiff opposition, this time from Kentuckians of the Union persuasion holed up in a brick railroad depot. The enemy pinned down one of Morgan's crack regiments in the streets of the city. Morgan was unsuccessful in bringing his guns to bear, and finally had to charge with the 2nd Kentucky and shoot through the windows and batter down the door. Morgan's nineteen year old brother was among those killed in the assault. Ellsworth's line tap produced the news that enemy cavalry was in the vicinity, so, prisoners and all, Morgan moved out towards Springfield.

At Bardstown on the 6th, two companies were dispatched to Brandenburg on the Ohio River to connect with Morgan's chief spy and to secure a boat to ferry his men across. Companies "D" of the 2nd and "A" of the 8th were sent east to Louisville to create a diversion and mask his real intentions. Earlier at Springfield, Company "H" of the 2nd was sacrificed to mislead the Federal cavalry.

The next morning when the Kentucky Division rode into Brandenburg they discovered that their comrades ha captured not one, but two steamers. Crossing the Ohio would be even easier than they reckoned, especially since the faced only token opposition on the Indiana shore. A Union riverboat appeared, but Morgan's artillery drove it away with a few accurate shots. By midnight Morgan had nine regiments totaling over 2400 men on the Indiana side of th river. He left the 9th Kentucky in their home state.

The first serious resistance was encountered at Corydon, Indiana from militia behind a barricade. One company charged the enemy but was repulsed. Morgan advanced two companies to flank the defenders. He placed a cannon on hill overlooking the town, and after it lobbed two shells into the midst of the militia they threw down their arms an surrendered. Morgan's men lost eight killed and thirty-three wounded in the skirmish. The Union casualties were considerably less but they suffered 300 captured.

Morgan left Corydon without the regrets of the townfolk. The next day the town newspaper printed: "About five P.M., after robbing the town to his heart's content, the king of American freebooters left, moving north on the Salem road, stealing as a matter of course as he went."

Riding into Salem, one of Morgan's lieutenants and twelve men routed the town's entire defense force of 150 men The looting then began in earnest here. "They pillaged like boys robbing an orchard," said Basil Duke. The troopers stole what they could, paid for some things with greenbacks stolen a few hours earlier, or in Confederate money if the shopkeeper was surly. They burned bridges, tore up railroad track and burned the depot. One nervous mill owner handed Morgan $1200 in cash to save his mill, but Morgan returned $200 saying that he didn't want to cheat anyone.

Ellsworth transmitted a false telegraph message saying that Morgan was on his way to Indianapolis, with General Forrest following close behind with another 2000 Rebel troopers. By monitoring enemy messages, Ellsworth learned that Union cavalry was gaining ground on Morgan's force.

Riding through Indiana wasn't too difficult. Although they faced thousands of militia, Morgan easily out-maneuvered them. Ellsworth's telegraph taps forewarned of impending roadblocks and pitfalls. Adding to this miasma was an enemy that seemed determined to shoot himself in the foot. Two companies of militia accidentally engaged each other near Lawrenceburg, Indiana, inflicting twenty-seven casualties upon themselves. Another militia unit burned a bridge in order to slow Morgan down, only to learn a short while later that Morgan had already crossed it earlier in the day.

To be sure, it wasn't all comedy. A skirmish near a railroad bridge cost Morgan six men killed. In addition, the fine Kentucky mounts that had served the men so well up to this point were beginning to fatigue, and fast horses were quite scarce in this Indiana farm country.

Early on the 13th the raiders crossed the Ohio. Union cavalry was hot on their heels, but Morgan confided to his officers that once past Cincinnati he felt that their troubles would be half over. Besides, Morgan reasoned, as long as they stayed in motion the enemy couldn't catch them. He was half right, but it was getting increasingly more difficult to keep his command in motion.

They passed around Cincinnati with great difficulty. The fatigued men were constantly failing asleep and straggling. Some troopers were compelled to change horses as many as four times as the raid took its toll on the horses as well. The night was misty and the only way to follow the leader was by following dust or the slaver horses dropped in the road. When the column finally stopped twenty-one miles east of Cincinnati they were only 2000 strong, but they had covered an incredible 90 miles in the last 24 hours.

Clashes

The clashes with enemy militia were now so common that the Rebels didn't even bother to parole their prisoners. They just destroyed their guns and rode on. Blooded horses were still being discarded along the way, and some enterprising farmers followed the raiders at a distance, gathering up fine bluegrass mounts, forever after to be the envy of their neighbors.

They reached the Ohio River at Buffington on the 18th, but Morgan didn't cross because it was already dark and the ford was heavily guarded. He decided to wait and try to cross the river early the next morning.

When morning came, Morgan learned that the Federal force had abandoned their breastworks, but before they could cross the ford they were attacked by two different cavalry divisions simultaneously. In the meantime, a Federal gunboat had steamed up and began lobbing shells into their midst. Morgan led some of his men out of the only open escape route, but behind his orderly withdrawal pandemonium reigned. Horses wild with fright overturned wagons, men rode around (desperately clutching merchandise looted from stores) abruptly changing direction with each bursting shell, and panic-stricken troopers rode over one another in terror. Then the Confederate defense collapsed altogether. Many troopers were pushed into a deep ravine by the sheer weight of a Union cavalry attack. Leeland Hathaway, Adjutant of the 14th Kentucky, had the dubious distinction of surrendering his regiment by waving in the air a white shirt that one of his troopers had earlier taken from an Indiana store. The battle cost the raiders 120 casualties and a whopping 700 prisoners.

Morgan, however, had no time to lament, for he had ridden to Reedsville where he succeeded in crossing 300 troopers to safety before a dreaded Union gunboat came steaming up the river and chased him away. At midnight he camped for two hours, then headed for the ford at Cheshire. However, the enemy came up and a battle ensued before Morgan reached the ford, and he took refuge on a high bluff. The Federal commander demanded Morgan's surrender and gave them forty minutes to comply. When a Confederate Lieutenant Colonel later appeared with a white flag, only 120 officers and men could be accounted for. Morgan and 600 of his men had slipped the leash and escaped.

On they rode, around enemy troop concentrations, over mountains, through rivers, piling up mile after fatiguing mile, in and out of one dangerous scrape after another. Once they took advantage of the fact that it was the Sabbath Day by stealing the horses of the parishioners attending service.

Finally the end came near Salineville, Ohio. Morgan, still riding "Glencoe", and his last faithful few surrendered to Federal forces. The great raid was over at last. Morgan would write other chapters in this war, including a daring prison break, but never again would he lead such a splendid band of horsemen, for men and horses of such stern quality were becoming scarce in the Confederacy in 1863.

REFERENCE

THE BOLD CAVALIERS by Dee A. Brown

A HISTORY OF MORGAN'S CAVALRY by Basil Duke

MORGAN'S RAID by Allan Keller

MORGAN'S RAID INTO OHIO by Max Gard

THE MORGAN RAID IN INDIANA AND OHIO by Arville L. Funk

THE OFFICIAL RECORDS OF THE WAR OF THE REBELLION

Back to The Zouave Vol II No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to The Zouave List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 The American Civil War Society

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com