INTRODUCTION

Researching information about the battle of Brawner Farm has been one of the most interesting and exciting experiences thus far for me as regards looking for material to print in THE ZOUAVE. Pitting the most elite units of each army against each other, the Iron Brigade for the Federals and the Stonewall Brigade for the Confederates, Brawner Farm seems to be the "dream" scenario for a JOHNNY REB game. It was a short battle, in that it lasted less than three hours total time, but it was a toe-to-toe fire fight that saw both sides stand their ground, even after incredible casualties had been inflicted. For the Iron Brigade, it was an initiation in battle that was passed with flying colors, and led to a well deserved reputation that still lives on in history. For the Stonewall Brigade, the battle led to a new-found respect for Federal troops, and in no way diminished their own reputation as the "Guard" troops of the Confederacy.

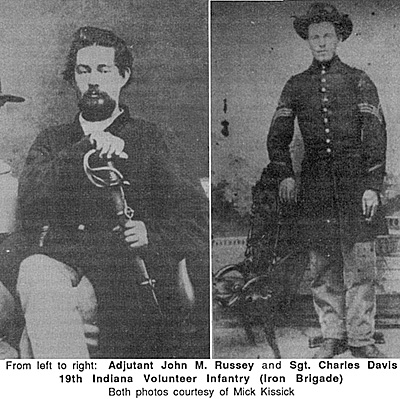

The "authority" on this battle is Alan D. Gaff, author of BRAVE MEN'S TEARS: THE IRON BRIGADE AT BRAWNER FARM, a book which I have read and which supplied me with most of the material presented in this scenario. The book is highly recommended for those interested in knowing more about this engagement, and can be obtained from Morningside Books in Dayton, Ohio. I wish to also acknowledge Mick Kissick of Indiana, whose passion for collecting images of the 19th Indiana has led me to deeply appreciate the soldiers of the Iron Brigade. His photographs, some shown in conjunction with this article, are quite rare and exhibit these western troops at their best.

Prelude To Battle

The Confederate high command of Lee and Jackson, realizing that McClellan was likely to retreat from in front of Richmond, decided to attack John Pope's Army of Virginia before it could be united with the Army of the Potomac. Jackson was left with this chore, beating the Federals at Cedar Mountain, which caused Pope to retreat behind the Rappahannock River to await reinforcements. The Confederate commanders were anxious to strike another blow, hoping to crush Pope's forces so they could turn their undivided attention towards McClellan.

On August 25, 1862 the Rebel column moved out with Ewell's Division leading the way, followed by the six brigades of A.P. Hill's Division, while General Taliaferro closed up the rear with the four brigades of Jackson's old division. With his usual obsession for secrecy, Jackson led the troops on a long march which culminated at Manassas Junction. Grabbing Union supply trains and depots along the way, very few gray-clad troops went hungry once at the important railroad junction.

Pope now realized that Jackson had marched around his flank and had a large force in his rear. He abandoned his line on the Rappahannock and ordered his army and the leading divisions of the Army of the Potomac to unite at Gainesville. The Union divisions were beginning to nip at the outnumbered Confederates and Jackson knew that he needed to move north or he would soon be trapped. His decision was to march to a place of previous success for the great southern commander - the battlefield of Manassas.

It is at this point that two Union commanders, both of whom were responsible for missing a chance to possibly defeat Jackson during and after the battle of Brawner Farm, began moving towards Gainesville. Irvin McDowell commanded the 3rd Corps of Pope's army, and his corps contained a division of 16 regiments under the command of Rufus King. McDowell would later be absent from his troops, leaving his subordinates without a commander. Rufus King, already sick from epileptic seizures, got McDowell's permission to retain control of his division. This was a mistake on both parts since King would end up being confused and out of commission during the battle, forcing the brigade commanders to coordinate troops amongst themselves.

The brigade leaders were John Hatch (senior brigadier), Abner Doubleday, Marsena Patrick, and John Gibbon, the latter leading what became known as the Iron Brigade. At this junction of the war only the 2nd Wisconsin had some battle experience, and for this was envied by the other regiments. Petty jealousies and determined, if foolish, compulsions to "follow the manual" prevented these brigade commanders from working together in the most efficient manner. While Gibbon's Iron Brigade met the fury of the Confederates, only Doubleday gave meaningful support. It was another case of Union befuddlement, which had plagued Federal arms since First Bull Run.

DayBreak

At daybreak on August 28th Bradley Johnson's brigade were the only Confederates near Brawner Farm. Members of the Ist Virginia Cavalry captured a Federal courier who had on his person an order which gave information on a planned Union attack by McDowell and Franz Sigel on Manassas. Johnson was dismayed to find out that he might have to confront Reynold's division, plus the brigades of Rufus King's division by himself, leading him to send a dispatch to Jackson calling for immediate assistance. His next step was to study the geography of the region to find his best place for defense against the expected Union attack. That place turned out to be the farm of John Brawner, with its elevation at points being 70 feet above any other land features.

The Federal column moved out, with some delay, led by Reynold's division and accompanied by McDowell himself. As they neared the vicinity of Brawner Farm, Confederate guns began shelling the column, inflicting a small number of casualties on the lead brigade (under the command of George Meade). McDowell and Reynolds conferred and decided to send out skirmishers to ascertain the strength of the enemy. Having already made the mistake of leaving Rufus King in charge of a division, McDowell made his second serious blunder by moving on to Manassas, taking Reynold's division with him, before the skirmishers returned with their report on enemy strength. Meade was the only outspoken opponent of the move and did not know what the skirmishers saw, since they had reported directly to Reynolds.

Of course, Bradley Johnson was tremendously relieved to see Reynolds marching off. Had such not occured, it surely would have led to the destruction of his brigade! In the meantime the captured dispatch was received by Jackson at about midday and he immediately told Taliaferro, "Move your division and attack the enemy", while also telling Ewell to "Support the attack". The Confederates rapidly moved past the Groveton and Sudley Road, deploying west and taking their positions in the woods. Skirmishers were sent to positions in front of the Confederate force, while the brigades of A.P. Hill arrived and were deployed on the left flank. Once the force was deployed, the Confederate soldiers sat down to eat and rest, unaware that large numbers of Federal troops were doing the same nearby.

While the men of King's division were ravenously eating a meal, General Pope was realizing that he had somehow "lost" Jackson's Rebel army. After capturing some stragglers from A.P. Hill's division, Pope decided that Jackson was marching on Centreville. He then ordered his entire army to march there. McDowell, having received the new orders told King to march on the Warrenton Pike toward Centreville. The corps commander then left with his escort and staff to consult with Reynolds.

The lead brigade of King's division, under the command of Edward Hatch, began moving and Hatch sent out the First Rhode Island Cavalry as a skirmish screen, supported by the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters. Gibbon's brigade was supposed to follow Hatch's men, but he never received the order. A foraging party of Federals was then captured by some Confederates and the Sharpshooters sent a report to Hatch stating that they had found the enemy in large numbers. Hatch believed the report to be exaggerated and his column continued to move toward Centreville.

It was at this point that the Staunton Artillery opened fire on the unsuspecting soldiers of Hatch's brigade. Initially panicking due to the suddenness of the attack, the Federals recovered and formed a skirmish line and a battery of ten pound Parrot Rifles took up counter-battery fire. The Union artillery was poorly placed and when another Rebel battery opened fire, they were caught, unable to effectively respond. The infantry were lying prone, attempting to escape the shell fragments exploding all around them. One soldier wrote that "most of us lay so close to the ground that we must have left our impression in the soil". The Union artillery wisely withdrew at this point, having lost a number of gunners.

King's division was spread over a two mile stretch of the turnpike, with Hatch's brigade in the lead, followed successively by Gibbon's, Doubleday's, and Patrick's brigades. Jackson's Confederate artillery began firing onto the column and the surprised Federals took cover wherever they could find it. Gibbon sent for his own battery and the Sixth Wisconsin tore holes in a fence at the roadside to allow the battery to move to high ground.

It was now 6:30 p.m. and all of the Union brigades were under artillery fire. General King could not be found, but this was later explained by Lt. E.K. Parker, who observed King in the midst of a seizure. Without their division commander present, Doubleday and Gibbon talked about the possibilities and decided that the Confederate artillery must be driven off. Neither of them realized that Jackson's army was present, being under the impression that the Rebel guns were horse artillery. Gibbon decided to attack the guns immediately.

The Iron Brigade Goes into Battle

Battle of Brawner Farm: Setting Up a Scenario

Back to The Zouave Vol I No. 5 Table of Contents

Back to The Zouave List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 The American Civil War Society

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com