Before reading on, I must explain that my treatment of warfare in general may seem too

light-hearted to some. The subject matter is so serious that I find the only way to retain any

sanity is through the use of humour. In the preamble to JOHNNY REB III, John Hill makes a,

similar but far more eloquent comment in regard to the captions used in some of the illustrations to that excellent set of rules.

Before reading on, I must explain that my treatment of warfare in general may seem too

light-hearted to some. The subject matter is so serious that I find the only way to retain any

sanity is through the use of humour. In the preamble to JOHNNY REB III, John Hill makes a,

similar but far more eloquent comment in regard to the captions used in some of the illustrations to that excellent set of rules.

Back in the Stone Age when I had access to a wargames club in Manchester, England, the highlight of the month was a re-fight of a historical battle. The twist in the tale was that the participants were told only the period but not the battle. If it were a Napoleonic Peninsular battle, then the terrain would be set out for a Bussaco or a Talavera and would usually be easily recognizable as such by the salient points on the battlefield and the initial dispositions of the troops.

Since the club specialized in Napoleonic wargaming, most players would be familiar with the arrival times of reinforcements, and of course the historical outcome of the battle. Our "Generals" would then attempt to avoid the mistakes committed by their historical counterparts and proceed to accomplish even greater blunders of their own making.

After a time this palled a little and, although this idea is not by any means new, it was decided to re-fight a couple of historical battles with troops other than those that were actually engaged. Since this could not be taken too far, such as attempting to wargame Shiloh with Roman Legions or the 101st Airborne, the troops had to fit into a similar period. For want of a better definition, the "Horse and Musket" period lends itself to this type of game. There were basically the three arms, Cavalry, Artillery and the PBI, which constituted the common denominator from the time of Frederick The Great to Napoleon III. Admittedly the traditional role of cavalry diminished as the period progressed. In later years troopers were actually encouraged to abandon their beloved animals and, against all the laws of nature, fight on foot. If the Good Lord had intended cavalrymen to fight dismounted, He would not have created the horse.

Until recently, my forte has been wargaming the Napoleonic Peninsular war, but of late I have developed a deep interest in the American Civil War and have been reading extensively over the past few years. I have acquired the appropriate rules and figures to enjoy engagements at all levels from skirmish (BROTHER AGAINST BROTHER) through regimental (JOHNNY REB III) to army command (FIRE & FURY). I use the now discontinued but exquisite 40mm ACW figures from Foundry and was lucky enough to be able to purchase what were almost the last of them. Thanks Neville.

"Our Welly" and "Friendship's Choice"

Now you may wonder where "Our Welly" and

"Friendship's Choice" [1] fit into the

scheme of things. Drawing on both my wargaming

passions, I propose to offer an American Civil War

scenario based on the battle of Salamanca. The

opposing commanders were The Duke of

Wellington, leading about 50,000 British and

Portuguese confronting Marechal Marmont

controlling an almost equal number of French.

This scenario lends itself beautifully to the FIRE &

FURY rules. The terrain in Spain, being mostly

vertical, also translates quite well into some of the

more rugged areas of the western theatre of the

War Between the States. The whole idea of

transferring this battle through time is, besides

offering some variety, to see if the effects of the

advances in weaponry and tactics after the

passage of nearly 50 years affects the outcome. It

should also come as a good surprise to the

members of your club if you tell them beforehand

that they are

about to fight an actual historical battle which,

for reasons that will become apparent later, we

have renamed "The Battle of Twin Peaks."

Inform them that the OOBs reflect the correct

brigade strengths present, but the commander's

names have been omitted to add some suspense.

It may also be an idea to offer a small prize to

the first person to guess the correct name of the

battle, but before doing so, it might pay to ensure

that there are no closet Napoleonic buffs lurking

in your club.

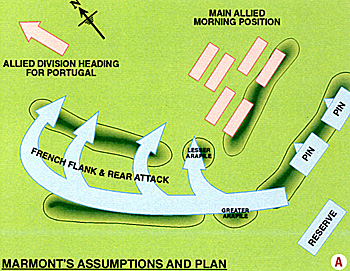

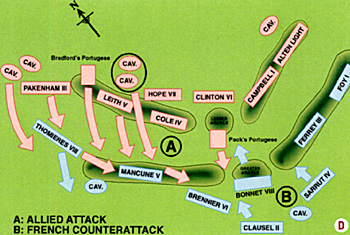

The battlefield of Salamanca

consists of two long parallel ranges of high

ground; each punctuated by a hill. The hill on the

north was called the Lesser Arapile and its

counterpart on the south, being some 100 feet

higher, the Greater Arapile. Of Marmont's eight

infantry divisions, he intended to pin Wellington

with two, keep one in reserve and use the other

five to march around the Allied army and attack

it in the flank and rear (see map A).

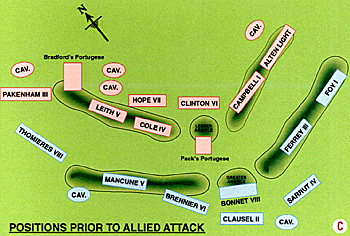

These led to a race along the inner

and outer arcs of the hills.

The French out

marched the Allies gaining the Greater Arapile

whilst the Allies held the Lesser Arapile, but in

so doing Marmont became strung out and invited

defeat in detail. His invitation was graciously

accepted (see maps C & D).

With that, he galloped over to Edward

Pakenham [4], the leader of the Allied Third Division

and said calmly, "Ned, do you see those fellows

over there? Throw your division into column and

drive them to the devil." Thomieres' division was

the first to feel the thunderbolt.

This was the beginning of a bad

afternoon for Marmont. First, he saw his plans

crumble before his eyes. Then, while running

to his horse in an attempt to retrieve the

situation he was severely wounded by

shrapnel from a deliberately aimed round: an

occurrence that was extremely rare in those

days. His succesor, Bonnet, was equally

unfortunate. He assurned the reigns of

command only to be hit by a musket ball within

minutes of his promotion. The task of leading

the French now fell to Clausel.

While the French command was in

tatters, the divisions of Maucune and Brennier

were in turn routed by the assaults of Bradford

and Leith with no little help from the British

cavalry lead by Le Marchant's brigade. This

cavalry charge was a prominent feature of the

battle, and although it cost Le Marchant his life,

contributed immensely to the outcome.

Wellington now assaulted the Greater

Arapile. Clausel however proved himself equal

to the occasion and not only repulsed the

attack, but drove the Allies back almost to the

foot of the Lesser Arapile with a counter attack

of his own and seriously threatened their centre.

This stroke eventually petered out

against the fresh troops of Clinton's Sixth

Division which up until now had been held in

reserve been committed by Wellington at just

the right moment. By this time, five of the

original eight French divisions had been

accounted for and the remainder of their army

fled the field covered by a masterly rearguard

action under first Ferrey and then Foy. Total

Allied casualties were 5,214 whereas those of

the French, although impossible to determine

accurately, were in the region of 14,000. In their

haste to depart, they also left behind some 20

cannon.

Writing in his journal six days later,

Foy was to compare Wellington's attack to

Frederick The Great's famous assault in the

oblique order at Leuthen .[5] A less exalted

French officer put it more succinctly when he

remarked that "Wellington had accounted for

forty thousand Frenchmen in forty minutes."

[1] "Our Welly" was one

of the more polite terms of affection for the Iron Duke. Others

included "Old Hooky" and "The bugger who leathers the French."

Napoleon, to his later regret, always regardcd him its "that Sepoy

General" because of Wellington's service in India.

"Friendship's Choice" came from it murmur which ran through

the French Grognards in 1809 when Napoleon created three new

Marshals of the Empire. It went:

More And Now for Something Completely Different

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF

THE BATTLE OF

SALAMANCA

On the morning of 22 July 1812,

Marechal Auguste Frederic Louis Viesse de

Marmont, duc de Raguse

[2]

was feeling pretty pleased with himself.

For over a month he had out manoeuvred

Wellington, who was considered to be the best

British general since Marlborough [3].

On the morning of 22 July 1812,

Marechal Auguste Frederic Louis Viesse de

Marmont, duc de Raguse

[2]

was feeling pretty pleased with himself.

For over a month he had out manoeuvred

Wellington, who was considered to be the best

British general since Marlborough [3].

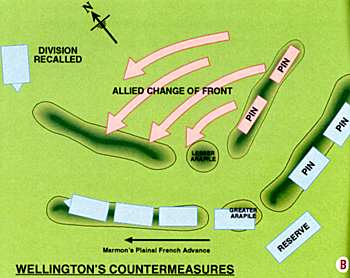

Should this

have come off, Marmont would have executed a

perfect example of his master's "manoeuvre sur

les derrieres" and no doubt cleared the Allies

from Spain. By midday the plan was well into

execution but Wellington had noticed the

movements and started taking countermeasures

of his own (see map B).

Should this

have come off, Marmont would have executed a

perfect example of his master's "manoeuvre sur

les derrieres" and no doubt cleared the Allies

from Spain. By midday the plan was well into

execution but Wellington had noticed the

movements and started taking countermeasures

of his own (see map B).

Seeing that a gap of a mile had

opened up between Marmont's three leading

divisions, Wellington, who was having a light

lunch at the time suddenly threw the remains of a

half-eaten chicken leg over his shoulder and

exclaimed, "By God! That will do!" He turned to

his Spanish liaison officer and remarked, "Mon

cher Alava, Marmont est perdu."

Seeing that a gap of a mile had

opened up between Marmont's three leading

divisions, Wellington, who was having a light

lunch at the time suddenly threw the remains of a

half-eaten chicken leg over his shoulder and

exclaimed, "By God! That will do!" He turned to

his Spanish liaison officer and remarked, "Mon

cher Alava, Marmont est perdu."

One moment it

had been marching happily along expecting to

come into the rear of the Allies, when suddenly

the entire Third Division appeared from the folds

in the ground in line of battle less than five

hundred yards from its right flank. The shock to

the French troops was so great that, although they

had heard that in every corporal's knapsack there was a Marshal's baton, at this particular moment they would have settled for a change of underwear.

One moment it

had been marching happily along expecting to

come into the rear of the Allies, when suddenly

the entire Third Division appeared from the folds

in the ground in line of battle less than five

hundred yards from its right flank. The shock to

the French troops was so great that, although they

had heard that in every corporal's knapsack there was a Marshal's baton, at this particular moment they would have settled for a change of underwear.

Footnotes

La France a nomme Macdonald,

L'armie a nomme

Oudinot,

L'amitie a nomme Marmont

[2] In the 19th century the French were generous in the

extreme when it came to conferring names. To preserve our forests, I have refrained from using the full version throughout.

[3] John Churchill, First Duke of Marlborough the revered ancestor of Sir Winston Churchill and no relation to the guy in the cigarette ad.

[4] This was Pakenham's finest hour. His worst zoos also his last. On 8 January 1815, he thought that he would show a newly promoted general of "colonial" militia the stuff of which veteran British troops were made. In this he succeeded admirably, leaving some 2,036 specimens littered over a small field just outside New Orleans. The newly promoted general's losses were eight killed and fifteen wounded. General Andrew "Old Hickory" Jackson went on to become the 7th President of the United States. Pakenham was saved the ignominy of having to explain his defeat as his judgement had proved not just flawed but fatal.

[5] This was praise indeed because Frederick was

admired even by Napoleon. After conquering Prussia in 1806, the Emperor went to pay his respects at Frederick's tomb. He stood in silent contemplation for some minutes and then turned to his Marshals and remarked rather pointedly, "Hats off Gentlemen! If Old Fritz had been alive today, we would not be here."

Part II: Introduction and Background

Part II: Scenario

Part II: Large Scenario Map (very slow: 220K)

Part II: Jumbo Scenario Map (extremely slow: 331K)

Part II: Scenario OOB (slow: 127K)

Back to The Zouave Number 52 Table of Contents

Back to The Zouave List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 The American Civil War Society

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com