In the American Civil War, the Union held many advantages over the Confederacy. Perhaps the most significant, yet least heralded, was the North's superior railroad system. It was organized and run as a single en ty called the United States Military Railroad (USMRR) by David McCallum and the indomitable Herman Haupt. By 1862 American hope for quick victory was dashed by the surprise defeat of the Union army at the First Battle Bull Run and the carnage at Shiloh, the first large-scale bloody battle.

In the American Civil War, the Union held many advantages over the Confederacy. Perhaps the most significant, yet least heralded, was the North's superior railroad system. It was organized and run as a single en ty called the United States Military Railroad (USMRR) by David McCallum and the indomitable Herman Haupt. By 1862 American hope for quick victory was dashed by the surprise defeat of the Union army at the First Battle Bull Run and the carnage at Shiloh, the first large-scale bloody battle.

Both sides realized they would need large armies to support their leaders' strategies. These armies require vast quantities of supply to sustain them in the field. For the first time the relative- ly young railroads would be called upon to satisfy the appetite of the nations' war machines. Leaders on both sides were quick to apply the railroads towards their war aims.

Last minute Southern reinforcements moved by rail turned the tide at First Bull Run. Yet, managing a large railroad network with its diverse and competing companies proved more than a task for both governments. Union Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, in surveying the tangled web of railroad logistics that existed in early 1862, decided that a railroad professional would be required to bring the Union advantage in railroad assets and technology to bear.

His search for a man to clean up the morass that fouled the Union supply system lead him to the dark recesses of the Hoosac tunnel in Western Massachusetts. There he found Herman Haupt engaged in both a technically and politically challenging task of digging the longest railroad tunnel to date.

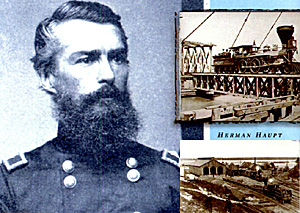

The 42-year-old Haupt was a West Point graduate with distinguished experience in both teaching engineering and building portions of the Pennsylvania Railroad in his home state. Haupt answered Stanton's call to duty in spite of the fact that he had risked a large portion of his own personal fortune in constructing the unfinished tunnel. Haupt arrived in Alexandria, Virginia to take command of the United States Military Railroad just in time to help expedite the flow of reinforcements to the Second Battle of Bull Run.

Haupt established his headquarters in Alexandria. At one point Alexandria rivaled Baltimore as the largest and busiest port on the Chesapeake. In 1862 it was still a significant port while its proximity to Washington and its rail yards made it militarily important. The Union occupied the city early in the war. Two railroads served Alexandria. The Orange and Alexandria Railroad (later the Southern) went west. The Loudoun and Hampshire radiated northwest towards Leesburg with a branch that connected with Washington, DC over the Long Bridge. The Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad had not yet established a rail connection to Alexandria.

Haupt recruited an assortment of frontier woodsmen, skilled craftsman and freed slaves to create a railroad construction corps that achieved amazing engineering and railroad building feats. One of his first notable achievements was the reconstruction of the bridge over Pohick Creek. The original bridge took three years to build. Haupt and his men rebuilt the 300 foot long and 100 foot tall trestle in less than a week. Abraham Lincoln, amazed upon seeing the bridge, commented, "that man Haupt has built a bridge using beanpoles and cornstalks".

Haupt recruited an assortment of frontier woodsmen, skilled craftsman and freed slaves to create a railroad construction corps that achieved amazing engineering and railroad building feats. One of his first notable achievements was the reconstruction of the bridge over Pohick Creek. The original bridge took three years to build. Haupt and his men rebuilt the 300 foot long and 100 foot tall trestle in less than a week. Abraham Lincoln, amazed upon seeing the bridge, commented, "that man Haupt has built a bridge using beanpoles and cornstalks".

In his Alexandria headquarters Haupt also developed prefabricated components to rapidly repair destroyed bridges as well as field methods to efficiently repair or destroy track.

Haupt's genius applied both to organizational as well as engineering skills. Upon taking command, the strongwilled Haupt swiftly reorganized the railroad. He instilled timetable and train order discipline to operate the railroad. On numerous occasions he clashed with superior Union generals over his perceived view of their interference with rail road operations. While Haupt's skillful management helped keep Union troops well supplied, battlefield results in 1862 were largely disappointing.

In spite of gaining a great Union victory at Antietam, Abraham Lincoln replaced General McClellan in November 1862. In his place Lincoln selected General Ambrose Burnside, a man who self-admittedly was incapable of command. Never-theless, General Burnside initiated a plan to move down the Rappahannock River to capture Fredericksburg as a prelude to an advance on Richmond.

To support the plan, Haupt immediately began preparations to change the Union Army's main supply line from the Orange and Alexandria Railroad to one using a combination of water and rail transport. He dispatched construction crews to Aquia Landing to restore the wharf there and to repair the connection to the Richmond, Fredricksburg and Potomac rail lines. He also supervised the construction of rail-to-barge transfer bridges at the both terminals of the proposed water route.

To transport the cars on the Potomac River, he designed, requisitioned materials and built unique railroad float barges. The floats consisted of two largesized Schuylkill barges, across which long timbers were placed supporting eight tracks. On these tracks loaded cars were run at Alexandria, towed sixty miles by steam tug to Aquia Landing. There, railroad crews unloaded the barges by pulling the cars. They then forwarded the cars without the break of bulk along the rebuilt line of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad to Falmouth, across from Fredericksburg on the north bank of the Rappahannock.

To transport the cars on the Potomac River, he designed, requisitioned materials and built unique railroad float barges. The floats consisted of two largesized Schuylkill barges, across which long timbers were placed supporting eight tracks. On these tracks loaded cars were run at Alexandria, towed sixty miles by steam tug to Aquia Landing. There, railroad crews unloaded the barges by pulling the cars. They then forwarded the cars without the break of bulk along the rebuilt line of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad to Falmouth, across from Fredericksburg on the north bank of the Rappahannock.

According to Haupt this was, "the first known attempt to transport cars by water with their cargoes unbroken. The Schuylkill barges performed admirably and thus was formed a new era in military railroad transportation. The length of the barges were sufficient for 8 tracks carrying eight cars, and two such floats would carry the sixteen cars which constituted a "train." All of this construction occurred over a period of two weeks.

Haupt was ready to support further military operations by November 17th. On November 22nd, he telegraphed General Burnside suggesting that Burnside move to Fredericksburg before General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate forces opposing him, could occupy and fortify the bluffs behind the city. However, General Burnside ignored the advice and waited three mores weeks at Falmouth before advancing across the Rappahannock. By then General Lee had concentrated his widely dispersed army from its winter quarters and was firmly entrenched on the heights behind Fredericksburg.

On December 13th, Burnside launched a futile attack on the strong Confederate position, The Union army suffered its bloodiest and most one-sided defeat of the war. The fact that Haupt would suggest strategic maneuvers to General Burnside was evidence of his own self-confidence and strong opinions.

On December 13th, Burnside launched a futile attack on the strong Confederate position, The Union army suffered its bloodiest and most one-sided defeat of the war. The fact that Haupt would suggest strategic maneuvers to General Burnside was evidence of his own self-confidence and strong opinions.

As the war progressed he continually suggested ideas and offered criticism to Lincoln and Secretary Stanton on all matters, some well beyond the realm of military logistics such as ways to reform the Navy and methods to build ironclad warships. Eventually this criticism that transcended his military jurisdiction angered Stanton and he forced Haupt to leave government service.

The changes and innovations Haupt wrought in the USMRR lasted well after his departure. General McCallum and others continued to capably manage the USMRR. In the end the superior resources of the Union, transported in large part by the USMRR, brought peace to the nation. Haupt returned to Massachusetts to finish his tunnel. It's still in use today.

Back to The Zouave Number 50 Table of Contents

Back to The Zouave List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 The American Civil War Society

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com