The great Japanese bastion at Rabaul on New Britain in the Bismarck Archipelago posed a double threat to the Allies from 1942 through the early months of 1944. Bristling with warships and airplanes, it menaced the line of communications from the United States to Australia, and it blocked any Allied advance along the north coast of New Guinea to the Philippines. Reduction of Rabaul was therefore the primary mission, during this period, of the Allied forces of the South and Southwest Pacific Areas. In executing this mission these forces fought a long series of ground, air, and naval battles spaced across a vast region.

Early Pacific Strategy

Before the Allies could move effectively against Rabaul itself, they had to clear the way by seizing Guadalcanal and driving the Japanese out of the Papuan Peninsula. With the successful conclusion of these two campaigns in early 1943, the South and Southwest Pacific forces completed the first phase of a series of offensive operations against Rabaul that had been ordered by the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff in July 1942. The strategic purpose of this series was defensive, the scale limited. The immediate aim of the joint Chiefs was, not to defeat the Japanese nation, but to protect Australia and New Zealand by halting the Japanese southward advance from Rabaul toward the air and sea lines of communication that joined the United States and Hawaii to Australia and New Zealand.

These orders stemmed from earlier, more fundamental decisions by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill, and the U.S.British Combined Chiefs of Staff, who from the very outset had agreed to defeat Germany first and then to concentrate against Japan. Pending Germany's defeat, the Allies decided on a defensive attitude in the Pacific. But within this framework they firmly resolved that Australia, New Zealand, the Hawaiian Islands, and Midway were not to be allowed to fall into Japanese hands. (For complete discussions on the development of this strategy see Maurice Matloff and Edwin M. Snell, Strategic Planning for Coalition War fare: 1941-1942 (Washington, 1953), Chs. I-VIII; Louis Morton, The Fall of the Philippines (Washington, 1953), Chs. II-IV, IX; and Mark Skinner Watson, Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans and Preparations (Washington, 1950), PP. 367-521. All are in the series, UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II See also Louis Morton's volumes on strategy, command, and logistics in the Pacific, now in preparation for the same series.)

Throughout the early months of 1942 the Japanese threat to the Allied line of communications had mounted steadily. The enemy's capture of Rabaul in January placed him in an excellent position to move south. Well situated in relation to Truk and the Palau Islands, Rabaul possessed a magnificent harbor as well as sites for several airfields. Only 44o nautical miles southwest of Rabaul lies the New Guinea coast, while Guadalcanal is but 565 nautical miles to the southeast. Thus the Japanese could advance southward covered all the way by land-based bombers. And since none of the islands in the Bismarck Archipelago-New Guinea-Solomons area lay beyond fighter-plane range of its neighbors, the Japanese could also cover their advance with fighters by building airstrips as they moved along. By May 1942 they had completed the occupation of the Bismarck Archipelago. They pushed south to establish bases at Lae and Salamaua on the northeast coast of New Guinea, and built airfields in the northern Solomons.

With the Japanese seemingly able to advance at will, the joint Chiefs had been making all possible efforts to protect Hawaii, Midway, New Zealand, and Australia by holding the lines of communication. Troops to reinforce existing Allied bases and to establish new bases were rushed overseas in early 1942. The 32d and 41st Divisions went to Australia. The 37th Division was dispatched to the Fijis, the Americal Division to New Caledonia, and the 147th Infantry to Tongatabu. Troops of the Americal Division, plus Navy and Marine units, occupied posts in the New Hebrides beginning in March. A Navy and Marine force held Samoa.

At this time the Japanese planned to cut the line of communications and isolate Australia by seizing the Fijis, Samoa, New Caledonia, and Port Moresby in New Guinea. But even before they were turned back from Port Moresby by the Allies during May, in the naval battle of the Coral Sea, the Japanese had postponed the attacks against the Fijis, New Caledonia, and Samoa and had planned instead the June attempt against Midway. Although they managed to seize a foothold in the Aleutians, they failed disastrously at Midway. With four aircraft carriers sunk and hundreds of planes and pilots lost, the Japanese could no longer continue their offensives. The Allies were thus able to take the initiative in the Pacific.

To conduct operations, the joint Chiefs organized the Pacific theater along lines which prevailed for the rest of the period of active hostilities. By agreement in March 1942 among the Allied nations concerned, they set up two huge commands, the Southwest Pacific Area and the Pacific Ocean Area.(Map 2) (The plural is customarily employed for the Pacific Ocean Areas, although the JCS directive establishing the command used "Area." See CCS 57/1, Memo, JCS for President, 30 Mar 42, title: Dirs to CINCPOA and to the Supreme Comdr SWPA, with Incls.)

The Southwest Pacific included Australia and adjacent waters, all the Netherlands Indies except Sumatra, and the Philippine Islands.

The vast Pacific Ocean Areas embraced nearly all the remainder of the Pacific Ocean. Unlike the Southwest Pacific, which was one unit, the Pacific Ocean Areas were divided into three parts-the South, Central, and North Pacific Areas. The North Pacific included the ocean reaches north of latitude 42 degrees north; the Central Pacific lay between 42 degrees north and the Equator.

The South Pacific Area, which lay south of the Equator, east of longitude 159 degrees east, and west of longitude 110 degrees west, was an enormous stretch of water and islands that included but one modern sovereign nation, the Dominion of New Zealand. Among the islands, many of them well known to readers of romantic fiction, were the French colony of New Caledonia, the British-French Condominium of the New Hebrides, and the Santa Cruz' Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, Cook, Society, and Marquesas Islands. The boundary separating the South and Southwest Pacific Areas (longitude 1590 cast) split the Solomon Islands.

General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander or, as he came to be called, Commander in Chief of the Southwest Pacific Area, with headquarters at Brisbane, Australia, in early 1943, commanded all land, air, and sea forces assigned by the several Allied governments. ("Supreme Commander" was the title used by CCS 57/1, 30 Mar 42. MacArthur seems to have preferred "Commander in Chief" and "Supreme Commander" fell into disuse.)

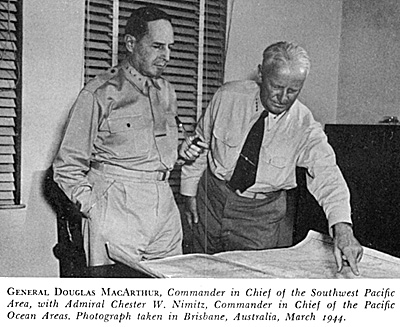

GENERAL DOUGLAS MacARTHUR, Commander in Chief of the Southwest Pacific

Area, with Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific

Ocean Areas. Photograph taken in Brisbane, Australia, March 1944.

GENERAL DOUGLAS MacARTHUR, Commander in Chief of the Southwest Pacific

Area, with Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific

Ocean Areas. Photograph taken in Brisbane, Australia, March 1944.

This famous and controversial general was enjoined from directly commanding any national force. In contrast Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who was concurrently Commander in Chief of the Pacific Ocean Areas, with authority over all Allied forces assigned, was also Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet. He exercised direct control over the North and Central Pacific Areas but in accordance with the joint Chiefs' instructions appointed a subordinate as commander of the South Pacific Area with headquarters first at Auckland, New Zealand, and later at Noum6a, New Caledonia. Like MacArthur, this officer was ineligible to command any national force directly. Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., the incumbent at the close of the Guadalcanal Campaign, replaced the original commander, Vice Adm. Robert L. Ghormley, on 18 October while the campaign was reaching its climax.

At the time of the Coral Sea engagement in May, a small Japanese force had garrisoned Tulagi in the Solomons, and shortly afterward the Japanese began building an airfield at nearby Lunga Point on Guadalcanal. just before they learned of the Japanese airfield under construction on Guadalcanal, the joint Chiefs capitalized on the Midway victory by ordering the South and Southwest Pacific Areas to begin the advance against Rabaul. The operations, as set forth in the joint Chiefs' orders on 2 July 1942, were divided into three phases. The first, or "Task One," was the seizure of Tulagi and Guadalcanal in the Solomons, and of the Santa Cruz Islands. Since possession of the Santa Cruz Islands did not prove necessary, they were never taken. Task Two included the capture of the remainder of the Japanese-held Solomons and of Lae, Salamaua, and other points on the northeast coast of New Guinea in the Southwest Pacific Area. Task Three was the seizure and occupation of Rabaul itself, and of adjacent positions. (Jt Dir for Offen Opris in SWPA Agreed on by U.S. CsOfS, 2 Jul 42, OPD 381, Sec 2, Case 83. Unlike other JCS directives, this paper bore no JCS number. It is also reproduced in JCS 112, 21 Sep 42, title: Mil Sit in the Pac.)

Command during Task One, which would be executed in the South Pacific Area, was entrusted to the South Pacific commander. Tasks Two and Three, to be carried out by South and Southwest Pacific Area forces entirely within the Southwest Pacific Area, were to be conducted under MacArthur's command.

When they received the joint Chiefs' directive, the commanders of the South and Southwest Pacific Areas met in Melbourne, Australia, to discuss the three tasks. They agreed that the advance should be governed by two basic concepts: the progressive forward movement of air forces and the isolation of Rabaul before the final assault. After the initial lunge into Guadalcanal, there would follow a series of advances to seize air and naval bases in New Guinea, New Britain, and the northern Solomons.

With these bases Allied fighter planes and bombers would be in position to cover the entire Bismarck Archipelago-eastern New Guinea-Solomons area and isolate Rabaul from the east, west, north, and south before troops were put ashore to capture the great base. (Dispatch, CINCSWPA and COMSOPAC to CofS USA, COMINCH, and CINCPAC, 8 Jul 42, CCR 82s, ABC 370.26 (7-8-42), Sec 1.)

The Joint Chiefs of Staff assigned the reinforced 1st Marine Division as the landing force for Task One. That unit, landing on Guadalcanal and Tulagi on 7 August 1942, quickly captured its major objectives. The Japanese reaction to the invasion was so violent and resolute, and Allied control over the air and sea routes so tenuous, that the campaign did not end then but dragged on for six months. It was not until February 1943 -- after two Army divisions and one more Marine division had been committed to the battle and six major naval engagements fought -- that Guadalcanal was completely wrested from the enemy. (For the history of the Guadalcanal Campaign see John Miller, jr., Guadalcanal: The First Oftensive, UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II (Washington, 1949); Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War H, Vol. IV, Coral Sea, Midway, and Submarine Actions (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1949), and Vol. V, The Struggle for Guadalcanal (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1949); Maj. John L. Zimmerman, USMCR, The Guadalcanal Campaign (Washington, 1949); and Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate, eds., The Army Air Forces in World War II, Vol. IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan- August 1942 to July 1944 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1950))

With the Guadalcanal victory, the Allies seized the initiative from the Japanese and halted their southward advance. The Japanese never attempted the assaults against the Filis, Samoa, and New Caledonia.

Just as the Guadalcanal Campaign was opening, a Japanese force landed at Buna, on the northeast coast of New Guinea's Papuan peninsula, and attempted to capture the vital Allied base at Port Moresby by crossing the towering Owen Stanley Range. But the offensive stalled, and MacArthur was able to move the 32d U.S. Division, the 7th Australian Division, and several additional American regimental combat teams and Australian infantry brigades against the Japanese beachheads at Buna, Gona, and Sanananda on the Papuan peninsula, as well as to establish bases at Milne Bay at Papua's tip and on Goodenough Island in the D'Entrecasteaux Group. (For a detailed discussion of the war in the Southwest Pacific, 1942-43, see Samuel Milner, Victory in Papua, UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II (Washington, 1957).)

At the beginning of 1943, with both the Guadalcanal and Papuan campaigns drawing to a successful close, the Allies could look forward to using Guadalcanal and Papua as bases for continuing the advance against Rabaul. In the Central Pacific, Admiral Nimitz could not undertake any offensive westward from Pearl Harbor and Midway until the line of communications to Australia was absolutely secure. At this time both Halsey and MacArthur were preparing plans for their campaigns against Rabaul, but had not yet submitted them to the joint Chiefs of Staff.

The Casablanca Conference

Although the joint Chiefs of Staff had not yet received detailed plans for Rabaul, they were well aware of the importance of the operations in the South and Southwest Pacific Areas. These operations naturally had to be considered in the light of global strategy and reviewed by the U.S.-British Combined Chiefs of Staff. (See Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, PP. 172-73; Min, JCS nitg, 22 Dec 42; Min, JPS intg, 16 Sep 42; JCS 112/1, 14 Oct 42; title: Mil Sit in the Pac. For a more detailed discussion see Ray S. Cline, Washington Command Post: The Operations Division, UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II (Washington, 1951), pp. 215-19, and Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1948), Ch. XXVIL See also John Miller, jr., "The Casablanca Conference and Pacific strategy," Military Affairs, XIII (Winter 1949), 4.

Unless otherwise indicated, this section is based on the proceedings and papers of the Casablanca Conference which are filed in regular sequence with the CCS and JCS minutes and papers. They were also printed and bound, along with the proceedings of the meetings attended by the President and Prime Minister, in a useful separate volumeCasablanca Conference: Papers and Minutes of Meetings.)

By the end of 1942, the joint Chiefs were concluding their study of Allied objectives for the year 194-3. President Roosevelt and the service chiefs were then preparino, to meet at Casablanca in French Morocco with Prime Minister Churchill and the British Chiefs in order to explore the problem fully and determine Allied objectives for the year, No final plan for the defeat of Japan had been prepared but the subject was being studied in Washington. (JPS 67/2, 4 Jan 43, title: Proposed Dir for a Campaign Plan for the Defeat of Japan.)

Also under discussion were the question of advancing against Japan through the North Pacific and the possibility of conducting operations in Burma to reopen the road to China. (Min, JPS rntgs, 2 and 9 Dec 42; Min, JCS mtgs, 25 Aug, 15 Sep, and 15 Dec 42, and 5 Jan 43; Min, CCS mtg, 6 Nov 42.)

Pacific operations, and the emphasis and support that the advance on Rabaul would receive, were significantly affected by decisions made at Casablanca. During the ten-day conference that began on 14 January the President, the Prime Minister, and the Combined Chiefs of Staff carefully weighed their strategic ends, apportioned the limited means available to accomplish them, and so determined Allied courses of action for 1943.

The Americans and British who met at Casablanca agreed on general objectives, but their plans differed in several important respects. The Americans wished the Allies to conduct a strategic offensive directly against Germany and to aid the Soviet Union, but they also favored strong action in the Pacific and Far East. It was imperative, in their view, to guarantee the security of Allied lines of communication there and to break the enemy hold on positions that threatened them. Convinced that China had to be kept in the war, they recommended that the British, with the aid of American ships and landing craft, recapture Burma so that the Burma Road could be reopened and the Allies could send more supplies to bolster Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek's armies. They wished to keep the initiative in the Southwest and South Pacific, to inflict heavy losses on theJapanese, and eventually to use Rabaul and nearby positions as bases for further advances. Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, expressed the hope that 30 percent of Allied military power could be deployed against the Japanese instead of the 15 percent which he estimated was then being used.

The British understandably shied away from enlarging the scope of Allied action in the Pacific. With the Germans right across the Channel from England, the British stressed the importance of concentrating against Germany first. while admitting the necessity for retaking Burma, they strongly emphasized the importance of aiding the Soviet Union. They promised to deploy their entire strength against Japan after the defeat of Germany, and suggested that the Japanese should meanwhile be contained by limited offensives. At the same time the British desired to extend the scope of Allied operations in the Mediterranean.

General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff, and Admiral King opposed what Marshall called "interminable operations in the Mediterranean." They advocated maintaining constant, unremitting pressure against the Japanese to prevent them from digging in and consolidating their gains. Warning that the American people would not stand for another Bataan, Marshall argued that sufficient resources must be kept in the Pacific; otherwise "a situation might arise in the Pacific at any time that would necessitate the United States regretfully withdrawing from the commitments in the European Theatre. (Min, CCS rntg, 17 Jan 43.)

Admiral King, pointing out the strategic importance of an advance across the Central Pacific to the Philippines, raised the question of where to go after Rabaul was captured. The British did not wish to make specific commitments for operations beyond Rabaul but suggested a meeting after its capture to decide the question.

By 23 January Americans and British had reconciled their differences over strategic objectives for 1943. They agreed to secure the sea communications in the Atlantic, to move supplies to the Soviet Union, to take Sicily, to continue their build-up of forces in Britain for the invasion of northern France, and a decision that was to have a marked effect on Pacific operations-to bomb Germany heavily in the Combined Bomber Offensive that was to be launched by midsummer 1943.

To make sure that none of these undertakings would be jeopardized by the need for diverting strength to prevent disaster in the Pacific, adequate forces would be maintained in the Pacific and Far East. What was considered "adequate" was not defined.

The Combined Chiefs agreed in principle that Burma was to be recaptured by the British and that they would meet later in the year to make final decisions. In the Pacific the Allies were to maintain constant pressure on Japan with the purpose of retaining the initiative and getting into position for a full-scale offensive once Germany had surrendered. Specifically, the Allies intended to capture Rabaul, make secure the Aleutians, and advance west through the Gilberts and Marshalls in the Central Pacific toward Truk and the Marianas. The Central Pacific advances were supposed to follow the capture of Rabaul.

Back to Table of Contents -- Operation Cartwheel

Back to World War Two: US Army List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com