I knew I had crossed the frontier into the former East Germany. It wasnít so much the zone of defoliated no mans land or the large sign next to the autobahn as it was the overall transformation of the terrain. The fields should have echoed the same luxuriant green on this side of the line as the other, but the former collective farms reveled in a dejected shade of brown. Older farm buildings and village houses croaked a lifeless desolation, interrupted only by the moan of pre-unity construction austerity.

The distinctive change of atmosphere altered my rose-colored vacation perception as I rolled along the autobahn at a steady 120kph (75mph). For 10 days, I had driven through the Black Forest, along the southern Alps, and up the central plain, passing well maintained villages and roads, exploring castles and medieval cities in pristine condition, and staying in modern gasthofs (inns) and small family-run hotels. Even the ruins are being rebuilt.

Perhaps I succumbed to the psychological delusion of crossing to the other side of an iron curtain that had not so much rusted as been sold for scrap. The western side of Germany looks as prosperous as any place in the U.S., or indeed, perhaps more so considering urban developers recycle older dwellings rather than pursue suburban sprawl.

A Hasty Advance

But I am a history buff and gamer, and I did not come across the Atlantic to completely play the tacky tourist spots. I decided to make a one-day detour across the former border to visit a pair of Napoleonic-era battlefields, Jena-Auerstedt (1806) and Lutzen (1813), in part due to the disappointment of discovering that Kulmbach castle, which houses a museum holding 300,000 toy soldiers, had closed at 3:00 p.m., and I had appeared at 3:30. Worse, it was Sunday, and German museums like this one remain closed on Monday, and I wasnít going to be around on Tuesday. Since you canít close a battlefield, I hatched the grand scheme to dash up the autobahn in the morn.

The heavily overcast skies did little to alter the oppressive mood of the countryside as the tired villages flashed by in a blur. As I exited the highway, the autumn gloom intensified with a thick fog rolling in to squash any panoramic views. I missed a turn, but corrected the error with a snappy U-turn. As I was to discover, half of the former East Germany is under construction and the other half lacks sufficient road signs.

The map showed a nice straight line along a prominent road from the autobahn to the town of Auerstedt. While not precisely the location of the Auerstedt battlefield, it would be close enough on an operational level before I had to delve into the tactical details of finding the battlefield. Yet somewhere along the way, in one of those depressing little villages, the road so prominent on the Michelin map turned into an patchwork quilt of uneven asphalt. Dreaded detours around partially rebuilt bridges funneled a long line of trucks and cars through narrow, twisting, buckling roads. Napoleon could at least count on pontoon bridges. I followed the stream of traffic.

I reached Dornburg. I had no desire to do so. It was many miles south of where I thought I had been heading. The French marshal Bernadotte had been at Dornburg in 1806. His corp departed the town far faster than I managed. Of course, I dealt with a dismantled bridge plus a completely closed main road. That left a single route over the river as I desperately tried to swing north towards Auerstedt. Down to the river and across a bridge I drove--to be stopped dead in my tracks. Make that stopped dead at the tracks--railroad tracks.

Making the Crossing

Dornburg is as cheerless as the other villages we had passed through on this winding adventure to Auerstedt. The predominant gray and black stone seemed burdened by age, neglect, and a range of despair as if it understood it would never be new again. I was stuck on the wrong side of the tracks, unable to go forward or back. Drivers exited their cars to wander about the road like ants with no sense of direction. They probably didnít share my impatience, as if this was the way things always work. I switched off the ignition as the temperature gauge in our black Opel started to climb towards the red zone. I simmered as my gaze wandered across the tracks. A spider web of power lines crisscrossing overhead complimented the grim realities of a train depot held up by grime.

The minutes hung as heavily as the fog. I saw the train emerge from the mist before I heard it--a trick of sound no doubt. Faded green paint melded with blackened steel as the solemn clicks finally announced the painful arrival of a passenger train.

The train passed, yet the line of cars and trucks moved not. The drivers continued their disinterested strolling. Another engine plodded into view from the opposite direction and stopped just short of the crossing. It waited. We waited. Dornburg waited.

A third train stumbled into view and headed down the tracks into the white oblivion of fog. Soon, with little fanfare and even less speed, the second train ended its reverie and followed, leaving the crossing as vacant as before.

Drivers returned to their vehicles and our community of traffic finally eased forward across the tracks. I was still headed in the wrong direction, but moving is better than sitting. The map showed yet another road that would curve me back to Auerstedt, but the road signs gave no indication. On a hunch, I wheeled the car right.

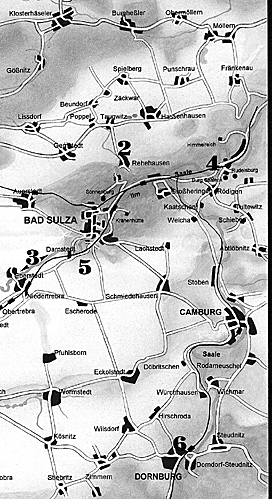

The road cut up the side of the cliff and strained the engine, but atop the cliff and high above what little could be seen of Dornburg below, the sky lightened, as if the sun agreed with my sense of direction. It was only 10 to 15 miles from the autobahn to the town, but many more delays and detours dogged my journey. I eventually reached Bad Sulza, stopped in the center of town, and fed a Deutchmark into the parking meter. The town seemed a bit more prosperous than Dornburg. It even boasted a tourist information center prominently marked with the international "i" symbol, although all I found was a rack of pamphlets rather than a person. Fortuitously, one contained a tactical map that actually mentioned the 1806 battlefield and showed a place with a battlefield diorama.

I was close, oh so close.

Marching to the Sound of the Guns

By now, I was determined to avoid earlier disasters from miserably marked roads. I marched into the Rathaus (town hall) and into the police station.

Empty.

The police station was dark and empty. Maybe the police take off on Mondays like the museums.

Elsewhere in the building, I spotted a fellow in a green jacket with some sort of patch on his sleeve. He looked official. Maybe he was a policeman. Maybe he was a forest ranger. He could have been the dogcatcher for all I cared, but he certainly knew the way forward. He pointed to the map I brought and said to follow the road to Eckartsberga, which held the diorama.

Now, I have been reading wargame maps for 25 years. I knew bloody well where the road on the map was, but where was the road in the town? In my best broken German, I asked. In his perfect German, he answered, but since I can understand only one word in 10 on a good day--and this was not one of the good days--I easily conjured up my best confused expression. I am glad he took pity on a poor tourist. Friendliness and a desire to help out a lost soul are universal on both sides of the former border. He walked out of the town hall with me and up the street a bit to point out the precise road. Itís a good thing he did, because there was no sign to show the way when I subsequently drove to the intersection.

Off I went, whizzing past collective farms with buildings even drearier than in the villages. I pulled into Eckartsberga and its maze of twisting cobblestoned streets. Every German town seems to post a map of the place. But what looks so clear on an overhead map becomes so useless once in a car rambling through three dimensions, and there was no mention of any diorama.

I headed into the Rathaus. At the top of the stairs, I opened a door and spied a secretary. She didnít know about a diorama, so she called over another person, who also didnít know. She then called someone on the phone, and between the four of us, figured out that the diorama sat in the tower of the castle just up the road on the right. Or was it turn right to get to the road? It didnít matter. It was just up the road. I thanked them profusely. Cold countryside. Warm people.

Castle Tonight, Too

Every German town also seems to have a castle, usually located on a street called Burgstrasse (Castle Street). I found the Strasse, turned right, and sped up the driveway leading to the ruins and a partially rebuilt tower. It was Monday. It was closed. At least the ticket window was closed, but the door was open. I entered the tower.

With a confidence born of desperation, I walked up to a worker wrestling with a stone and asked about the diorama. He pointed to a narrow stairway. I didnít ask twice and ascended the worn stone steps two at a time. If he tried to throw me out, he would be amazed at how much of the German language I could forget.

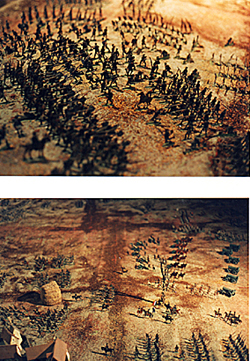

I rounded a corner, then another, and then emerged into a room with 6,000 miniature soldiers battling inside a large glass case. They were "flats," so called because the Prussian and French troops are stamped out on a thin steel sheet, rather than the three-dimensional figures we are used to seeing at U.S. museums. But they were all in color, even if the lighting in a damp tower proved to be a tad dim.

I rounded a corner, then another, and then emerged into a room with 6,000 miniature soldiers battling inside a large glass case. They were "flats," so called because the Prussian and French troops are stamped out on a thin steel sheet, rather than the three-dimensional figures we are used to seeing at U.S. museums. But they were all in color, even if the lighting in a damp tower proved to be a tad dim.

The flats at Eckartsberga, Northwest of Bad Sulza and West of the battlefield.

There, in the front, sat the village of Hassenhausen, which changed hands many times during the battle. Off to the left were the Prussian cavalry regiments formed up into their ill-fated attack upon the French infantry deployed in protective squares. The French artillery in the center stared at the Prussian masses, with French Marshal Davout directing its efforts. Somewhere over there was The Duke of Brunswick directing Prussian efforts. The Battle of Auerstedt lived inside the glass, fueled by imagination and a hundred works of history. I might have tapped out the Pas De Charge with my fingers on the case, but I was not conscious of it. No, I was not conscious of it at all.

I was so close to the battlefield--and getting closer.

Avant, Mon Enfants!

Sure, I climbed to the top of the tower for a look around, although visibility was hampered by the continued overcast skies and low-flying clouds. I even took a photo in the general direction of the battlefield. But as I walked back to the car, the sun burst into view, blasting through the clouds with the force of a 12 pounder cannon.

Back inside the Opel, I revved the engine and bolted for Hassenhausen, for once guided by actual road signs and not some supernatural ability with a mental compass. For two long weary hours, four if you count the autobahn time, I tried to reach the Auerstedt battlefield. Now, it was down to a four kilometer rush. If Davoutís corp had taken this long in 1806, there would have been no battle of Auerstedt.

Hassenhausen rose into view before we reached the outskirts. I slowed upon entering the village and parked the car on a sidestreet. Traffic was virtually nonexistent. Urban development was virtually nonexistent. The fields surrounding Hassenhausen remain fields. Some were recently tilled, so unless you wished to trespass in the mud, you were limited to the road and farm tracks.

And unless you knew the battle, that was about it. A marble monument to the battle sits inside a low iron fence. Across the street, there is supposedly a museum, although poorly marked, and of course, closed.

Down the road outside Hassenhausen, in the farmerís field and accessible via a rutted dirt track, sits a monument to the fallen Duke of Brunswick, one of the many fatalities of that day 190 years ago. Half a klick away, an even worse farm track will take you to Prussian HQ, if you wish to test the welds on your rent-a-carís muffler. If you take a side street past the village of Rehehausen, youíll discover a single sign: ďSchlachtfeld 1806Ē (Battlefield 1806).

Down the road outside Hassenhausen, in the farmerís field and accessible via a rutted dirt track, sits a monument to the fallen Duke of Brunswick, one of the many fatalities of that day 190 years ago. Half a klick away, an even worse farm track will take you to Prussian HQ, if you wish to test the welds on your rent-a-carís muffler. If you take a side street past the village of Rehehausen, youíll discover a single sign: ďSchlachtfeld 1806Ē (Battlefield 1806).

No visitorís center like at our own U.S. Civil War battlefields. No battlefield tours with Park Service rangers. No maps. Just a sign and a couple monuments.

At right (top): Intrepid history buff finds the sign marking the battlefield in between Hasenhausen and Rehehausen. (bottom): Hasenhausen outskirts facing east.

But also, no urban sprawl. No fast foods, cheap trinket shops, or crass commercialism. Silence reigns over the battlefield, interrupted by the occasional car, truck, and gamer. Sure, some development has taken place, but the undulating terrain with occasional flat areas remains pretty much the way it was in 1806, or so I wish to delude myself.

It had taken so long to find Auerstedt, that Jena and Lutzen were out of the question, much as it pained me to admit. Finding Auerstedt was an adventure game in itself. For those of us who have pulled out traditional hex-gridded wargames, computerized wargames, or military miniatures and replayed the battle of Auerstedt, walking the terrain remains the best way to get a feel for the battlefield.

It is difficult to imagine riding a horse along the several mile-long front, positioning regiments, deciding where reserves should be stationed, and executing a deliberate plan of attack or defense. We gamers do this every time we pull out a board, set up a table, or boot code. Davout did it in reality and on the fly, seizing an opportunity to cross the river, march up the Kosen defile, deploy upon the field, and win a battle against the overwhelming numbers of Prussians sent to crush them. Some day, virtual reality will fool us into thinking we turned back the clock 190 years. For now, standing on a road with a head full of battle accounts will have to do.

After the Battle

If I had been better prepared, I would have photocopied some of the maps and descriptions of Auerstedt sitting at home in books. I frankly expected more discussion and information about a battle that crushed the Prussian state and helped ensure Napoleonís dominance for a half a decade. Maybe it was because it was such a glaring defeat that Germany ignores it. If the German government is foresighted, it will preserve the valuable real estate of military history from the sort of entrepreneurial excess that plagues US battlefields.

If I had been better prepared, I would have photocopied some of the maps and descriptions of Auerstedt sitting at home in books. I frankly expected more discussion and information about a battle that crushed the Prussian state and helped ensure Napoleonís dominance for a half a decade. Maybe it was because it was such a glaring defeat that Germany ignores it. If the German government is foresighted, it will preserve the valuable real estate of military history from the sort of entrepreneurial excess that plagues US battlefields.

At right (from left to right): Auerstadt memorial, diorama shows attack on Hasenhausen, and memorial to the prince.

Still, Hassenhausen and the Auerstedt battlefield remain safe--so far--at least until the improvements to the former East German infrastructure becomes as precise and navigable as that in the former West Germany. In the meantime, a TV documentary, the most high resolution computerized map, or a paper wargame board pale before an actual visit to a battlefield. It is only then that you can go back to your game and appreciate the genius or stupidity of the historical commanders while you push your regiments into gaming combat. But before that happens, you sometimes have to play a real-life adventure game of reaching the battlefield.

Back to War Lore: The List

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com