In these days when Britain would be hard-pressed to send a battalion of infantry

to the Falkland Islands were the Argentinians to decide to take them over, it

is stimulating to read of a remarkable piece of Victorian logistics that occurred 111

years ago.

In these days when Britain would be hard-pressed to send a battalion of infantry

to the Falkland Islands were the Argentinians to decide to take them over, it

is stimulating to read of a remarkable piece of Victorian logistics that occurred 111

years ago.

In 1868, General Sir Robert Napier took a force of 10,000 men in convoy from India, landing at Annesley Bay, and then marched more than 400 miles over unknown country under tropical conditions to release British prisoners held by King Theodore of Abyssinia. It was a tremendous effort for that time, for all transport had to be brought from either India or Europe, mules were bought up by the thousand in Spain, Italy and Asia Minor; camels were purchased in Egypt and Arabia; transport trains, including elephants to carry the artillery, were organised in India.

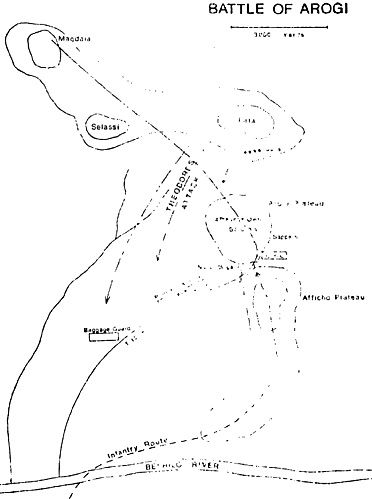

By the time the force reached the plateau of Dalanta, some eight miles from Magdala, Theodore's capital, on 7 April, it was only about 4,000 strong, as it had left detachments en route to cover the line of communications. It was formed of the 4th and 33rd Regiments together with native infantry and cavalry; the Naval Brigade; and some mountain guns. There were 460 cavalry, including two squadrons of the 3rd Dragoon Guards. The area to be advanced over on the following day, probably against strong enemy opposition, was an impressive one.

Descending some 4,000 feet to the Bachelo River, the ground rose beyond it in a succession of billows one behind the other, with the steep crags of Magdala rising above a saddle formed between two steep peaks. To the right was Fala with a flat top; to the left, a few hundred feet higher, was Selassi. The only ascent seemed to be by a zig-zag road cut in the face of Fala. Native encampments and gun positions could be seen through field-glasses. From the Bachelo River a steep ravine ran up through the hills almost directly towards Magdala, carrying a road made by Theodore for the transport of his cannon.

At daybreak on 10 April the advance guard (under General Sir Charles Stavely) began to descend the road into the ravine, preceded by Colonel Phayre and 800 Sappers and Miners. It was very hot, and the men filled their water-bottles from the thick and muddy water of the river before the advance force, consisting of the 4th Regiment, Royal Engineers, and native infantry, struck off to the right over the hills that would lead them on to the Arogi plateau opposite Fala, where the enemy had positioned some guns. It was an extremely difficult climb and the mounted officers could only begin to scramble their horses up the slopes after the Pioneers had cut a rough track for them.

Misunderstanding a message snet back by Colonel Phayre that his Sappers and Miners held the head of the valley and that the road was quite practicable, the baggage train and guns, protected only by a guard of 100 men of the 4th Regiment, was left to proceed alone up the ravine in full view of the enemy. Realising how vulnerable this was, General Staveley, leading the advance-guard, ordered the men of the 4th Regiment (who were lying exhausted on the ground after climbing tile first hill) to press forward with all speed to protect the baggage-train. Spurred on by the sudden crash of an Abyssinian gun and an explosion as the shell struck the ground, the tired men rose to their feet and began climbing. By now large bodies of white-clad infantry and cavalry were pouring down the road, the scarlet robes of their leaders and their multi-coloured flags making colourful patches.

The 4th Regiment were scrambling up a steep slope that led to the crest of a low hill; a small ravine lay to its front and, 100 feet below, there was a plateau extending to the foot of Fala and Selassi. The little ravine widened out to the left until it fell into the main valley, half a mile away - the Punjab Pioneers were immediately dispatched to this point. They were joined by the naval rocket brigade at the point where the side valley ran into the main valley. With well drilled speed the sailors unloaded the rocket projectors from the mules and, in less than a minute after they had arrived from the crest, a rocket whizzed out-over the plain, followed by a stream of erratic missiles whistling and hissing in rapid succession.

The Abyssinians momentarily halted but, urged on by their chiefs, came plunging rapidly forward again until they were only about 100 yards from the edge of the slope up which the 4th Regiment was laboriously toiling. In the nick of time the line of skirmishers breasted the slope and set foot on the plateau, to open a rapid fire with their Snider rifles. It was the first time that these breeches drove them further away from Magdala.

Large numbers of Abyssinians were rushing forward away to the left upon the few Punjab Pioneers who were defending the head of the road. Before they were actually among the Indian troops, Colonel Penn's steel guns had arrived at the top of the road and unlimbered by the side of the Punjabis, to fire on the natives over open sights. Those Abyssinians directly attacking the baggage-train were halted by the massed fire of the breech-loading rifles of that part of the 4th Regiment acting as escort to the baggage. Then, scattered by the artillery fire and disorganised by the unexpectedly rapid fire of the infantry, the Abyssinians were dispersed by a series of bayonet-charges. In a few minutes the remnants of the force that had poured confidently down into the valley fled up the opposite side of the ravine under heavy fire from the infantry and rockets on their flanks. Throughout the action, the Abyssinian guns from Fala maintained a constant but very erratic fire, so that most of their shells passed high over the heads of the troops and burst behind them.

Theodore's army had suffered a crushing defeat - only about 600 of the 5,000 who had sallied out remained. The courage of the poorly-armed Abyssinians had impressed the British soldiers who saw that they had not thrown away their weapons as they retreated, nor had they gone back in rout. Not a single man was killed on the British side and only 30 were slightly wounded.

This battle makes a quite classic wargame and is one of the most memorable fought on a Thursday evening in Southampton. So much so that a certain wargamer commanding the 4th Kings Own Baluchis on the Arogi Plateau failed to move with sufficient speed, was overwhelmed and wiped out to a man by the on-rushing natives. So disgusted was he by this and the rules that alluwed it that, although a regular for many years, he never returned and never fought another wargame with us! Of course, this all stems back to the question of rules for these Colonial games, whether they should be tailored to allow the natives a better chance or whether they should be of such pristine accuracy as to allow the high fire-power and the greater discipline of the white troops and their native allies to constantly prevail. It depends whether you want a good wargame or absolute historical accuracy - and the two are sometimes hard to simultaneously obtain.

To return to our battle - stringent timing is required, the cues being taken from the narrative given here, if the various movements of bodies of troops are to coincide with real-life and give a wargame the same degree of tension and so finely balanced as in 1868. It would be delightful to print other wargamers battle reports of this nature - so get cracking!

Back to Table of Contents -- Wargamer's Newsletter #210

To Wargamer's Newsletter List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1979 by Donald Featherstone.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com