This year's Military Historical Society tour was different in that it was more personalised, more emotional because of the familiarity of the names and places and the relative nearness of the events were brought even closer by having three World War I veterans with us. Our guide lecturers were David Chandler of the R.M.A. and Brigadier Denis O'Flaherty DSO.

Disembarking from the hovercraft at Calais we were returning to memorable places such as Calais, inescapably linked with the 1940 defence by Brigadier Nicholson and his Riflemen (including many personal friends in the Queen Vic's) and the 3rd R.T.R. The towns and village:mwe drove through on that sunny Sunday bore familiar names as the Brigadier ably filled us in on places of interest.

We spent three nights at a good hotel in St. Quentin and, blessed with good weather, began our exploration/pilgrimage to the Somme almost 60 years after the tragic events of 1916. One does not lightly tread the ground where 60,000 of our countrymen fell in a single day and if we found it difficult to associate those grim events with the peaceful rolling agricultural countryside around us basking under the soft Spring sunshine then the vivid descriptions of experienced Denis O'Flaherty conjured it all up for us.

We began at the Butte de Warlincourt, the limit of the British advance on the Somme in 1916, climbed this small mound rising like a pimple in the flat countryside and obviously of vital tactical importance. At Courcelette we stopped to look at the Tank Memorial and photograph our two World War I tank corps men - Jason Addy and Maurice Tiffin, standing proudly in front of it.

Although sixty years have passed there are signs on all sides of past events - jumping from the coach at this Memorial I landed on what seemed to be a large stone but turned out to be a fair size piece of shell which became the first of the many momentos I found and took home. On the other side of the road were the ruins of Pozieres Windmill where an inscription reminds us that here the Australian dead lay thicker than ever seen in any other part of France.

We viewed the imposing Theipval Memorial bearing the names of 73,000 men with no known graves and walked through the small cemetery behind it. Directed by the Brigadier, we turned our binoculars on High and Delville Woods, studied the lay of the land and the exposed glacis over which our infantry attacked at Beaumont Hamel.

We saw the mine crater on Hawthorn Ridge and then walked to the now grass covered trenches and shell holes in the area of the Scottish Memorial at Beaumont Hamel and in Newfoundland Park. Here are still trenches and the stakes that held barbed wire, the ground is so open that a small dog would be visible for a very long way so it is understandable how from 738 Newfoundland infantry who attacked less than 70 were remaining within half an hour. The famed Y Ravine is now grassed over and lay peaceful under the sun but its tactical significance remains quite evident and there are ample signs of dug-outs and fortifications in it.

We climbed the tower in the Ulster Memorial Park on the site of the German Schwaben Redoubt, saw momentos collected by the custodian and listened to him talking of human remains still being discovered and buried.

At La Boisselle, the coach stopped on a fairly busy stretch of road bordered by a cultivated green slope where, Denis O'Flaherty told us the British dead were lying in rows like toy soldiers that had been knocked over with their khaki stretching through the entire valley causing the green fields to take on the appearance of plough. Here we saw the Lochnager mine crater, a huge pit caused by exploding 60,000 lbs of Amatyl under the German lines. Awe inspiring and seeming almost big enough to take St. Paul's Cathedral, it taxed the imagination to think of the effect on that morning when it was exploded.

On the following day we traversed Delville Wood which is still a mass of trenches, craters and shell-holes; heard the Brigadier talk of the many thousands of South Africans who were killed in this area and visited their cemetery. We went to Flers where, as an old Royal Tank Regiment man, I was thrilled to see the ground over which the very first tank attack in history took place.

Later in the day we visited Cambrai and lunched in a lane by the side of Havrincourt Wood near to where one of our party, Jason Addy, remembers his tank harbouring overnight on the 19th/20th November 1917. We trudged across country, following the advance of this greatest of all early tank attacks and followed the road down to Flesquieres. Road operations were in progress and a bulldozer had carved away a strip of ground on either side of the road above the ditch, exposing a sort of cross-section of the fields above and presenting us with a veritable treasure house of souvenirs. Embedded in the soft ground were pieces of shell, water-bottles, gas-masks, smashed and rusty rifle barrels, even a machinegun barrel, barbed wire, etc., etc. Obviously all the ground in this area and on the Somme is a mass of war relies and we were told that even the tractors working in the fields in the area have an armour plate underneath them to protect the drivers from explosions that their vehicles might cause.

On the following day we made a long haul from St. Quentin to Verdun, taking in the Napoleonic battlefield of Laon en route.

We crossed the area Chemin-des-Dames where the French were engaged in very heavy fighting during World War I and came to an area marked by some old entrenchments, a French 75mm and the German gun and a World War II French Renault R35 tank. Here we paused for photographs and yet another reflective gaze over these rolling areas of ground for which so much blood was spilt.

Verdun

To a Frenchman the name Verdun has a highly emotive ring causing them to retain far more relatively untouched relies than can probably be seen elsewhere in France or Belgium. When one considers that 74 out of the 90 existing French infantry divisions took part in the Battle for Verdun then the magnitude of this conflict on the French nation can be more readily understood. I recall as a boy seeing films of the epic 'struggles for the forts - Douamont and Vaux - now we had the opportunity of actually standing on their shell-torn and shattered remains. The fighting within these dank, dark and dripping tunnels must have been war at its very worst and even today many of them are barred and marked as being too dangerous to enter. The armoured gun turrets and cupolas still remain in position and the riven masonry, even in the bright light of day, did not stretch the imagination too far to imagine what it must have been like in 1916. At Fort Vaux there are still hunks of 12-inch thick steel from shattered turrets lying around on the groundp while unexploded shells can be seen half exposed in the cratered ground.

We went to all the salient points of the area, including a visit to the Ossuary, a huge building with a tower from which a revolving searchlight nightly bathes the battlefield, containing the bones of 155,000 dead - they can be seen in jumbled piles through glass windows at the rear of the building and if you have never seen thousands of shattered skulls and femurs piled like firewood then I can assure you it has a sobering effect. In fact, just as the Somme touched our native pride so Verdun depressed us with a true consciousness of war at its worst. The whole area is covered with sm-1 conifers, explained by notices in French, German and English saying that the ground is too impregnated with human remains and the materid'I of war to be capable of cultivation so small fir trees have been planted. There are frequent skull and crossbone signs indicating areas still considered unsafe to be trodden.

The tour also included digressions into other wars - we saw the Windmill at Valmy and viewed the ground over which the French Revolutionary armies in 1792, by their victory in a so-called battle (in reality a cannonade) over Germans and Brunswickers really got the Napoleonic Wars off to a flying start. An arch-enthusiast for the Marlburian Wars, David Chandler was determined to repair the omission of never having seen the battlefield of Malplaquet in 1709 so we drove through Sedan (memories of 1870 and 1940 ably described by our lecturers) to reach the Franco/Belgium border near the battlefield of Malplaquet which was discussed at length. Personally, I seemed to find a greater thrill out of being told that the road on which - we were standing was that taken by Haig's British Ist Corps on their retreat from Mons in 1914.

In the bright sunshine of early evening we arrived at Vimy Ridge where, after being conducted through some of the tunnels and viewing the reconstructed German and Canadian entrenchments, we climbed up to the impressive Canadian Memorial standing high on the Ridge. Viewed from below this was a rising piece of ground over which we knew the Canadians had charged in a snow storm in March 1917 but when we actually got onto the top and walked around the Memorial itself we realised its importance because the whole area of France lay stretched out before us, naked to our gaze with the slag heaps of Loos on the far horizon. It truly burst upon us the great advantage the Germans had in many of their rising-ground positions during World War I whilst giving a slight inkling of the triumphant feeling that the Canadians must have had when they got up there and saw what lay before them.

Later that evening we arrived at Ypres just in time to take part in the touching evening ceremony at the Menin Gate where Belgian firemen play the Last Post on bugles presented to them by an English regiment. Our World War I veterans were genuinely affected as might be expected and found names on the walls of the Menin Gate of men with whom they had served.

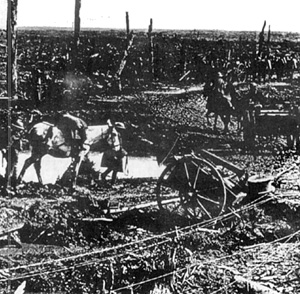

Next morning we only had a little while to spare before dashing to Boulogne - another tradition of these tours is that we should arrive to catch the boat with minutes to spare and this was to be no exception! Nevertheless, Denis O'Flaherty managed to race us round as much as possible of the Ypres Salient, going up to Passchendaele and visiting the large Tynecot cemetery. We went into many of these cemeteries which are sad but glorious places, never failing to stir ones feelings with both emotion and pride. It was possible from this area to see stretched out before us the flat and open and once waterlogged ground over which so much terrible fighting took place for so long. Every village through which we passed bore a familiar name and it can be no exaggeration to say that they must be indelibly printed on the hearts of our fathers and grandfathers.

We found a German cemetery at Langemarck where three original German pillboxes were built into the cemetery wall - in their operative hey-day they were facing the Pilkelm Ridge and must have seen considerable action.

In London we dispersed, going our various ways - not without a little regret and sadness because the comradeship and goodwill on these tours has to be experienced to be believed and those of us who go regularly year after year have come to regard them as a regular part of our lives like Christmas or Easter. Plans are already going ahead for next year, in fact discussions as to the place to be visited were tinged with some feeling - they range from Northern Italy, the Normandy beaches and Waterloo, Portugal to as far as South Africa - I can hardly wait to be told where I am going in 1977!

Back to Table of Contents -- Wargamer's Newsletter # 174

To Wargamer's Newsletter List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1976 by Donald Featherstone.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com