In the days before photography, you commissioned painters to record your famous victories. The Austrian Military Museum in Vienna has one particularly outstanding example, a set of huge canvasses painted by Peeter Snayers in the early 17th century, showing Austrian successes in the Thirty Years War. I have never seen anything quite like these. Your first impression is that he has painted the armies man for man, but when you count a cavalry unit you find there are about fifty or sixty horsemen. Was this the average size for those days, or has Snayers simplified? Perhaps some pike and shot enthusiast could tell us. He could perhaps also comment on the different formations used, whether they are typical of the nations concerned or simply reflect the difference between a defensive and an attacking order of battle.

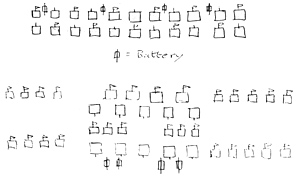

For instance, the Battle of Diedenhofen in 1639, on two huge paintings about eight feet wide each, shows the (defending) French army drawn up with alternating cavalry and infantry units in two lines thus:

For instance, the Battle of Diedenhofen in 1639, on two huge paintings about eight feet wide each, shows the (defending) French army drawn up with alternating cavalry and infantry units in two lines thus:

In front of the two lines was a-fairly thick line of skirmishers, whereas the (attacking) Austrian army had none at all. Makes one think of 1805. The Austrians had cannon massed in front of their infantry centre, and their army was much more elaborately arranged, with layer upon layer of centre reserves, the rear cavalry covering the intervals between foot units:

As I have tried to show in the drawing, the Austrian horse are mostly in very small units, the only exceptions being the rear four.

The section on 18th century campaigns includes a large painting of the battle of Kolin, 1757, where they defeated Frederick. This painting actually had numbers painted on it in various places, and an explanation at the foot of it of how the battle proceeded.

I could not remember having seen a painter do this before, although it seems a sensible thing to do, as these were not intended as great works of art, presumably, simply as descriptions of what the battle looked like. Like the paintings from the previous century, this one tried to show the complete battle, including the towns and roads over whicl one or both armies had arrived before deploying. The long lines of white-uniformed Austrians looked very impressive, and I was again reminded how ideal this particular period is for wargaming purposes, with the simpler formations and more cohesive armies.

There was also a reminder in this room of my own home district, as one alcove was occupied by a huge picture of Marshal Loudon on horseback, and the long Banffshire face looked very familiar. I assume from the name (there were lots of Loudons in our town) that hewas descended from a Scottish emigrant, like Barclay, Lauriston and Macdonald in the Napoleonic period.

For obvious reasons, the 1793-1815 period is not so fully represented, until you come to the Allied victories towards the end. An interesting point, remembering the arguments about formations used, is that many battles are shown being fought in line - and I am referring to illustrations of entire battlefields, not those annoying things showing two regiments and clouds of smoke and a group of staff officers, as I do not think those things have any value.

A curious feature of the very large museum is that they have hardly any literature or copies of pictures for sale, so you have to go round with notebook and pencil yourself. My own Austrian Napoleonics being all Line regiments, I was interested in the sketches of the Grenz (frontier district) regiments which appear to have been used as light infantry for much of this period. Also in the examples of Grenadiers' headgear, as I had seen illustrations in books on uniforms showing the stripes on the fur caps sometimes matching the facing colours and sometimes shown as a uniform gold colour. The museum examples showed that the two systems were used, during different stages of the Napoleonic period. So your grenadiers can have either the one or the other, whichever you think looks better.

For naval wargamers, the Museum has a magnificent display of the entire Austrian Empire navy during the 1914-18 war, the highly detailed models being arranged in squadrons as regards the main fleet, and then the others are grouped according to which bases they operated from. It was a very large navy by 1975 standards, but of manageable size (compared with the enormous British and German fleets) and thus very suitable for a naval wargames campaign, I would have thought.

Maps and Visibility: Marchfeld

Two other points from staying in Austria: I noticed again how misleading maps can be regarding visibility. I walked over a fair portion of the Marchfeld plain, where Essling and later Wagram were fought, and on the map it looks featureless and flat, from the Danube to where the first slight rise starts about five miles away. In fact it is rare to get a clear view for a mile. The undulations are almost imperceptible, but are just enough to continually close off the view. Villages, or small tree lines, even rough hedges, all mask what you could otherwise see. No wonder commanders did not know what was going on even in the' next village.

Movement Speed

The second point concerned movement. It was obvious from all the accounts of the 1800-1813 campaigns at least that our wargame movement speeds are much too fast. I know ours have usua1ly assumed that, as the average person can walk at three miles an hour along roads, two miles an hour for large units of infantry was a reasonable figure, reducing to just under a mile per hour for deployed infantry. moving and firing, with horsed troops able to move at 4-8 m.p.h. on roads. In point of fact, ONE mile an hour seems to have been the average during this period, both NEAR and ON the battlefield: Literally dozens of examples could be quoted as proof from all the central European battles (I have not looked into this question yet as regards the Peninsula theatre of operations), so I need not waste space with them.

The significance as far as practical wargaming is concerned is that if this slow speed is worked into the rules it should help to prevent those over-fast reactions which make many wargames so untypical of their period. You know the sort of thing: player A builds up a reserve behind some trees, and judging that his opponent cannot have many troops opposite that sector, launches this reserve for a decisive attack. Player B sees it start and either starts moving troops to counter it immediately if the local rules allow you to change orders from bound to bound, or will start moving spare troops to the threatened area at accelerated speed as soon as he is next allowed to change orders (wargamers who restrict changes in initial battle plans often allow faster moves to be taken when at a safe distance from the enemy, representing infantry, say, moving up at the double).

In both cases, Player A need not have bothered to work out his opponent's dispositions and he has wasted his skill in timing the attack, as it will be met with almost equal or greater forces. So it seems to me that if game move distances are reduced to give this realistic average of about 1 m.p.h. it would be a further factor in forcing players to work out a proper plan at the start of a game, detailing some units to act in reserve in specified sectors, as they would not be able to move troops from one sector to a distant part of the front as fast as a surprise attack can reach there, especially in conjunction with one of the usual game systems for ensuring that the overall commander can react to a new threat only after a specified period of time which represents messenger movements, staff work, etc.

Figures

On returning home, I looked around for figures which I could paint as some of the more colourful Landwehr regiments which the Austrians used increasingly from 1809 onwards. The shop sold me some nice Jager figures which matched some of the Landwehr uniforms and fitted in well enough with my old Austrian Line figures, dating mostly from 1966-70. I remembered that the same maker did a good British marine who would fit the bill for some of the other Landwehr units. Yes, the shop stocked them, but when the figures were put on the counter they were quite different in scale from the Jagers, and had massive bodies and arms particularly. The catalogue nmber was the same as it had been for the marine produced by the same firm for the last few years, so I was lucky that I could see the change and refuse the figures.

I just wondered about people buying "blind" by post, and hoped that the word is always passed round quickly when these changes take place. I feel that the manufacturers have got away very lightly with the whole business of altering figure sizes. There were some grumbles in the Newsletter some months ago, but nothing much besides, in public, at any rate. And yet surely it was a great pity losing the easy mixability of figures and accessories which existed for so many years down to about 1972. In our district nearly a dozen people owned Napoleonic armies larger than they needed for any one game, some having up to 6-700 figures.

Two, wargamers at least preferred to make their own figures, beautifully converted from Airfix, rather than buy 'factory' figures, and this paid dividends particularly with cavalry, as the metal cavalry put out in the early years was not up to the infantry standard, with poor horses. But even the smaller Airfix figures fitted in easily with the Hinton Hunts, early Minifigs, etc., which were usually about 22-23mm in height.

The change to a slightly taller metal figure, and longer better horses was quite acceptable, but then manufacturers increased the height again and/or started increasing the width and mass of the figures to such an extent that they will no longer fit into the armies so many people owned. The smaller of the old figures look like schoolboys alongside rugby forwards, when used in a wargame with the new massive figures. Instead of a uniform scale all over the country, there is pressure to adopt 25mm or over figures or drop to 12mm or 15mm, which will presumably become popular in proportion as wargamers get fed up at how few of the new huge "25mm" figures you can get on an average table. And all this change, which suits only the manufacturers, has been brought in gradually. If any firm in 1970 or so had introduced the present huge new figures I am sure it would have got its fingers badly burned, as it would have been so much more obvious just how they would not fit in with the smaller size which was then used universally.

This last paragraph is only a grumble, although connected in one way with the main part. The incident made me feel, perhaps wrongly, that, in wargaming as in other fields these days, makers are producing what they want to sell, not what the public asks for.

Back to Table of Contents -- Wargamer's Newsletter # 163

To Wargamer's Newsletter List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1975 by Donald Featherstone.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com