The recent introduction of a fine range of wargames

figures for this period (by Miniature Figurines) and the

forthcoming publication of the book "WARGAMING IN THE

PIKE-AND-SHOT PERIOD" by Donald Featherstone (David and

Charles) may well turn the attention of wargamers towards

this colourful 250 years period.

The recent introduction of a fine range of wargames

figures for this period (by Miniature Figurines) and the

forthcoming publication of the book "WARGAMING IN THE

PIKE-AND-SHOT PERIOD" by Donald Featherstone (David and

Charles) may well turn the attention of wargamers towards

this colourful 250 years period.

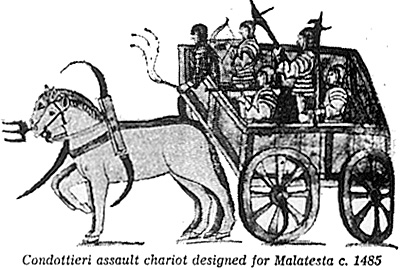

Condottieri assault chariot designed for Malatesta C. 1485

Another recently published work is also valuable in this connection -- here is Bill Thurbon's review:

MERCENARIES AND THEIR MASTERS: A STUDY OF WARFARE IN RENAISSANCE ITALY-by Michael Mallett. Bodley Head; C-4.50p).

- This is a learned, but very readable study of the

Condottieri. From the bands of Free Companions and freelances

who terrorised 14th century Europe to the 15th century

Condottieri, and their gradual development into state armies.

The author shows how they fitted into the pattern of society,

how the majority of the leaders were of noble blood, and

above all the kind of war they fought. We see the development

from archers (few in number) and crossbowmen, to viand

gunners and arquebusiers: the use of cannon and the power of

their heavy cavalry. The author brings out the fact that the

battles were far bloodier affairsthan Macchiavelli would have us believe.

For wargamers looking for fresh fields, here is the ideal subject and book.

In a recent TIMES, Michael Howard the military historian, wrote on this book and the military roots of the Renaissance.

"We would all like to believe that war and positive social development are incompatible, that inter armos silent both artes and leges and that man can be happy, prosperous and productive only in time of peace.

To do so we have to explain away not only fifth-century Athens but fifteenth-century Italy; both societies almost obsessed with warfare. There is little evidence that the first Italian printers groaned ruefully as their presses turned out the works of Vegetius and Aelian, that Italian architects lamented their fate in having to design fortifications as well as churches, that Italian craftsmen lavished any less care on arms and armour than they did on the instruments of' peace. Italian Illumanist Literature describes martial deeds and martial virtues with every sign of relish, and one Lypical fifteenth-century writer congratulated his age on having had "the good fortune to witness a revival of the long-lost art of warfare."- Yet the culture of renaissance Italy was not exactly barbaric. Odd.

English specialists on the Italian renaissance, usually gentle and gentlemanly art historians, have not entirely averted their eyes from the military aspects of their subject, because there is really nowhere else for them to look. The military were all-pervasive. But they have not been very informative about them, and the standard works on the subject are now at least fifty years old, The last few years, however, have witnessed a revival of renaissance military studies and it would not be invidious to point out its fons et origo as Professor John Hale: as gentle and gentlemanly a scholar as any in Bloomsbury but the first for many years to make it clear to the world that if one is studying Renaissance Italy one is studying a society at war.

It is nice to think of Bartolomeo Colleone and Federigo de Montefeltro and Francesco Sforza simply as the patrons of art and scholarship and to forget the horrible military realities on which their fame and wealth rested. It would be equally nice to think of Carnegie and Rockefeller and Ford simply as philanthropists; but that is not what historians are for.

Three years ago Mr. Geoffey Trease gave us a beautifully illustrated account of the rise and fall of the condottieri for the general reader. Now, in Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy (Bodley Head - C4.50p, pp 284), Michael Mallett, without forfeiting readability, digs rather deeper and studies them as an institution in the social and economic context of their time. He shows how they developed out of the bands of routier freelances who terrorised fourteenthcentury Europe; how and why war became commercialised in Italy and the terms on which they served; where they fitted into the social pattern (they were usually noble, otherwise they would not have had a force at their disposal or the capacity to create one); and above all the kind of war they fought.

Macchiavelli's famous picture of the condottieri as conducting elaborate and expensive mockwars, rather like professional wrestlers screaming in simulated agony, has never been taken entirely seriously by historians, but it has never been quite discredited. Mr. Mallett sets it in perspective.

Condottieri certainly avoided battle if they could; their investment in their forces was enormous, and to blue the whole thing in a few hours was very bad business indeed. Certainly they themselves, mounted on horseback in their beautifully-designed armour, usually came through with life and limb if not reputation intact, but battles were none the less horrible. For instance Macchiavelli wrote of the battle of Molinella in 1467 that "some horses were wounded and some prisoners were taken but no death occurred." Mr. Mallett suggests that in fact six hundred men died and quotes contemporary chronicles as saying that for days afterwards the whole countryside smelt of death as the bodies rotted in the ditches.

War was thus as vile then as it has ever been - that is if one belongs to a culture that considers war to be vile. The Italians of the Renaissance did not. That ideal of Italian humanism, the complete man, expressed his virtueas much in war as in any other activity -- perhaps even more. The condottieri were not professional hacks employed by peaceful citizens but honoured and sometimes dominant members of the community. Those who, like Macchiavelli, criticised them did so not out of pacific anti-militarism but on the grounds that the community should not hire them to do a job it ought to be doing itself.

Posterity will of course regard our contemporary pacific values as far superior to those of fifteenth-century Italy. Yet may not posterity, weighing the merits of the arts produced within our society against those which emanated from the unabashed militarism of the Renaissance, be very mildly perplexed?

Back to Table of Contents -- Wargamer's Newsletter # 154

To Wargamer's Newsletter List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1975 by Donald Featherstone.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com