The formative idea behind the CD-Rom is the interplay and

cross-pollination between history and game.

The formative idea behind the CD-Rom is the interplay and

cross-pollination between history and game.

Screen-shot of our Beta working version.

The operational study will show situation maps for each day of the campaign, and from the 15th of June, three situations per day, each with a brief narrative of events.

However, it will contain studies of major sub-systems:

- Staff Quality and Leadership

- Equipment, Arms & Training

- Supply & Morale

- Geographic Factors

The theory of larger unit operations ... planning and conducting campaigns.... The disposition of forces, selection of objectives, and actions taken to weaken or to outmaneuver the enemy [and] set the terms of the next battle.

To show you how these major sub-systems worked, we will provide examples from histories of the campaign.

You will discover things that have never been written in any journal or history text. We will employ the US Army's Operational Concepts, considering Initiative, Depth, Agility and Synchronization. In examining these concepts, we will keep our focus on the Operational level of war, "the theory of larger unit operations ... planning and conducting campaigns. ... The disposition of forces, selection of objectives, and actions taken to weaken or to outmaneuver the enemy [and] set the terms of the next battle."

We will go beyond this to a three-dimensional look at the subject, that only the techniques of game design can provide. For our first CD, studying the Waterloo campaign, we discovered a major missing puzzle piece, a very overlooked subject of an over-worked subject area: The 15th of June.

All historians agree, "Napoleon's concentration of the Army prior to the onset of the campaign was a master. piece of brilliant planning." But what, exactly, did that plan consist of?

Historians have focused on the events of the 16th and 18th June, while largely ignoring the 15th except for the crossing and skirmish at Charleroi; merely covering the subject in a few summarizing statements. All historians agree, "Napoleon's concentration of the Army prior to the onset of the campaign was a masterpiece of brilliant planning."

But what, exactly, did that plan consist of? What was so brilliant about it? Who conceived the plan and who implemented it? What was the role of Marshal Soult? Which divisions crossed the Sambre at which bridges? None of that has been addressed. We have looked at the staff personnel and compared them against the veterans of Imperial Headquarters from prior campaigns, identifying the key experienced personnel and their capacities.

We have gone back to the correspondences to unlock the mystery of the 15th of June, to show you for the first time in print, exactly what happened, and what went wrong, on the 15th of June. The critical delays in the French crossing of the Sambre very likely preserved the Prussian I corps for the fight at Ligny on the 16th.

A historian, at heart, is a story-teller, and he is re-telling the story as it has been handed down to him. Moving beyond this concept of history, the wargame provides new insights in our quest for understanding.

The question presented itself only because of the way of framing information in wargame design. It causes us to look for information that no regular historian would consider looking for. A historian, at heart, is a story-teller, and he is re-telling the story as it has been handed down to him. Moving beyond this concept of history, the wargame provides new insights in our quest for understanding.

Our games allow us to go beyond the accepted truths of history. If all sources agree that d'Erlon camped at Solre - sur- Sambre on the 14th of June, we can show whether that was likely, or even possible. At first blush it seems unnecessary that d'Erlon's Corps should have crossed the Sambre only to recross the next day!

A wargamer would avoid crossing over the Sambre only to have to re-cross at Charleroi or Thum. This is the first thing one notices when examining the French Army's march of concentration between the 6th and the 14th of June. The most efficient general would not have crossed d'Erlon's I Corps over the Sambre into Solre, but would have retained the corps on the other bank, ready to cross into Belgium via the left bank of the river, moving first to Binche and then Fontaine I'Eveque.

This Corps would be able to screen the flank for the other corps crossing to their right. Instead of just adding to the knotted congestion of masses trying to funnel through a few narrow bridges, they would have complete freedom of maneuver. Further, as we know, the appearance of the corps south of Mons would have played into Wellington's fears of a French advance toward his channel ports. Yet we know that d'Erlon's Corps was delayed in its arrival at Quatre Bras on the 16th; far from providing a screen for the main column, it provided no assistance to the II Corps and performed no mission of value at all on the critical 16th of June.

To hide the movements of an Army, would Napoleon order a concentration to the southeast of the Sambre? The river would clearly be a most formidable obstacle to Allied scouts gathering intelligence. The crossings could be strictly guarded. Or did Napoleon order the concentration of the army before he had yet determined a route of march?

Perhaps both are true-Napoleon wanted the army concentrated and able to unite, and he perhaps found the left bank too close to the frontier. The hazard entailed by this concentration was the congestion of the roads south of Charleroi, a hazard which only excellent staff work could ameliorate.

Napoleon's correspondences for the period of the 6th to the 14th of June provide a clue. The Charleroi route had already been decided upon the 13th, but that does not mean the entire army had to march by that one road. In fact, the whole point of the 'bataillon carre' (the operational arrangement of the corps into a flexible quincunx) was to have the corps moving on parallel routes. Therefore in addition to the bridge at Charleroi, troops crossed at Marchienne, Chatelet, and Thuin. Nonetheless, too much of the army was aimed at the Charleroi bridge.

What happened on that road that day?

What happened on that road that day?

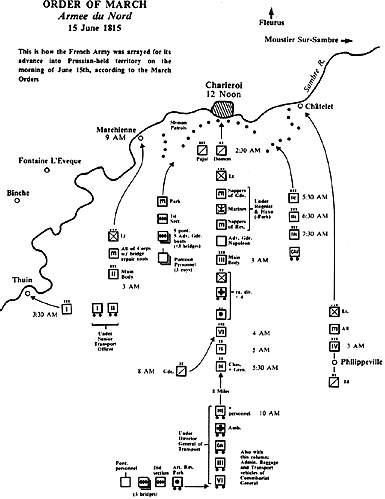

The diagram is the only one published showing the order of march for the 15th of June, as it would have looked if executed exactly.

However, what the column actually looked like was a different matter, for you would see the orderless III Corps blocking the road, with resultant confusion and entangling of columns behind.

Jumbo Illustration of Napoleon's March Order 15 June 1815 (slow: 168K)

Imagine what two corps columns looked like when entangled: wagons abandoned on the road, troops wandering off to grab a quick smoke or an unguarded chicken. Napoleon's Army was notorious for its lax march discipline ... 'you go ahead, we'll catch up later' was acceptable.

This simple question has opened a very big subject area that no one, neither wargame designer nor historian, has ever yet touched upon. And that is, what practices were entailed in the use of terrain as a screen? How would the move of a major formation normally be hidden? Is a river like the Sambre an effective screen? We know that Napoleon sent orders to the border posts to prevent anything from crossing, neither letters, carriages, or barges. As the I Corps moved off, cavalry patrols were to be left behind to screen as usual. Our investigation has just begun.

There is, however, no doubt that a long and difficult campaign would have followed a French victory at Waterloo. With the British Army no longer a factor, and the best Prussian troops defeated, only the Austrian and south German and Russian armies would remain.

The Austrian Army's performance was, as in 1814, lackluster-Rapp's V Corps was able to check their advance. The question was, whether the Austrian Army would unite with the Russians, so that Napoleon had to face another Leipzig-scale battle, or whether he could fight them separately. Even with the 100,000 recruits expected in July, he would still have been outnumbered at least two-to-one.

One can speculate that, immediately upon taking Brussels, Napoleon would have split his Armee du Nord, leaving Ney to mop-up while he took the relatively unscathed III, IV and Guard corps to support Rapp. There is little doubt he would have driven the Austrian Army out of France before the Russians arrived.

"If [Napoleon] had succeeded in defeating Wellington and Blucher, he would have been in a good position to bring the Army of the North to the support of Rapp, LeCourbe and Suchet. For that matter, the less enthusiastic of the Allies might even try to turn their coats again, as several had done several times in the past. The operations on the frontier were a calculated risk." (Al Nofi, Strategy & Tactics Magazine)

After a success against the Austrians we could look for a replay of the 1814 campaign, except that this time Napoleon would have had a victorious, and much more numerous army fighting farther east, away from Paris and the recruiting centers.

The French would indeed be outnumbered 2: 1, but a large part of that numerical advantage was chimerical--made up of unwilling south Germans and Austrians--who were more concerned with preserving their own troops and their geopolitical position vis-a-vis Prussia, for which purpose a strong France, within her own frontiers, was not unacceptable. But would Napoleon have had the sense to accept a reasonable negotiated settlement?

Back to Wargame Design Vol. 2 Nr. 5 Table of Contents

Back to Wargame Design List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Operational Studies Group.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com