I am pleased to see that Massena will soon get to take on that upstart Wellesley, again. In Spain, large armies starve and small ones are defeated.

I'm a bit perverse as a gamer. Tough, frustrating situations appeal to me. I remember the Spanish war scenario from War & Peace. I loved it. My opponents at the time hated it. I also remember being the "only" kid on my block to like AH's 1914.

There are certain battles that haunt me about which I always hunger to see a simulation. Waterloo is one of those. So I in part agree with the comment in WD#2 that a good game on that subject is needed. My point is this-A battle like Albuera can support the kind of treatment used by the La Bataille Rules because of its size. The situation is manageable by the Player.

Waterloo-no. There the player needs more distance from battlefield management (a point that goes also for Borodino or Fuentes de Oftoro, Antietam or the Wilderness battles that also haunt me). Size, complexity, the ability of the game rules to basically manage themselves (if you know what I mean) are important, not just for playability but for the player to get a true sense of what managing a force of many corps or divisions is really like and the real level of control a commander can exert on such large battles.

The system in GMT's Battles of Waterloo does not manage itself and if you have seen A Famous Victory or Fields of Glory you realize Richard Berg was really designing a system to manage early 18th c. battles, for there his system works. I have been tinkering recently with the notion that something akin to Perla's Bloodiest Day (derived from AH's Stalingrad: the Turning Point and Thunder at Casino) or Games USA's Borodino is needed.

But tinkering is not designing! (My two successful designs were a rip-off of PanzerBlitz to simulate Ctesiphon in WWI and a simulation of Alexander's War against Persia that worked well enough, but needed three different scale maps: Greece & Aegean, Middle East, Iranian Plateau eastward with certain rule changes for each scale to make it work properly. Oh, and when I say successful I mean that my friends liked playing them in spite of homemade boards and pieces.)

In any case, Mr. Zucker, I would like to clarify my position on the graphics of the reissue of Napoleon at Bay. First, the pieces are an improvement over the AH version of the game. Second the AH map is a very poor second to the new map. I am glad you have new cardboard and someone else to die cut the pieces for 1806.

The most frustrating thing is to have to "exacto" out pieces and then reglue them because the face paper & cardboard adhesion is faulty. I'm not quite sure who Dean Essig uses but his cardboard and die-cutting are almost faultless. Whomever COA uses is better than AH has been for some time. Of course, not being an insider I don't understand what AH is doing now or who owns them. They sure aren't the boys from Avalon Hill whose new releases we breathlessly awaited back in the 60's and 70's. I buy their solitaire stuff.

You say there is some thought of reissuing Struggle of Nations using the same small hex format. Two things made the original somewhat irritating to set-up. First the command display (Yes, I know it's called the organization display ... ) was far too big ... I would suggest that if any part of the game materials needed mounting these command displays do. In fact what would be particularly handy would be to have them set-up so that they would fit on a number of 8.5" x 11" boards that could be scattered about the gaming table wherever they might fit.

[Ed. note: you can xerox onto cardstock.]

Regarding the small pieces in the original Struggle of Nations. While slick pieces are very pleasant for the actual combat units, the leaders need to be done in that dull cardboard style in later AH games or in the original Napoleon at Bay. The practical problems with those small pieces were their tendency to come unstacked. and the difficulty in reading their labels. I would use lettering that pushed to the edges of the counter, make the pieces with dull rather than slick surfaces, and experiment with thicker cardboard to see if that might add more stability to the stack and make the pieces easier to handle.

It also occurs to me that the fortress hexes on the map were a little hard to see. The second hex of the fortress was printed in a light yellow. I would use some shade of red, or bite the bullet and draw the fortress in two hexes.

There was a rule on page 12 of the rules for Struggle of Nations labelled "Effects on AQT column of AP Accumulation" that always seemed contradicted by other rules and that was extremely cumbersome. In the games I have played, I have never used it.

I kind of wish Bonaparte in Italy could use the small hex format just for size sake. Measure a typical kitchen or dining room table ... factor in the "Organization Displays" and you might get a hint at my size concern. ...

Roger L. Pearce

Baltimore, Maryland

Regarding your unfinished projects, the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe advises,

- "Until one is committed, there is

hesitancy, the chance to draw back,

always ineffectiveness. Concerning all

acts of initiative (and creation) there is

one elementary truth, the ignorance of

which kills countless ideas and

splendid plans: that the moment one

definitely commits oneself, then

Providence moves too. All sorts of

things occur to help one that would

never otherwise have occurred. A

whole stream of events issues from the

decision, raising in one's favor all

manner of unforeseen incidents and

meetings and material assistance,

which no man could have dreamed

would have come his way.

"Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it.

You are right about the Massena situation; it will be frustrating for the player, hopefully in an enlightening way. I also liked " 1914," and to this day the idea of the game appeals to me, even to the green ink used in the rules.

If you could explain exactly what it means for a game's rules to manage themselves, you would be on to something. A related point would be to explore why the Berg system works in 18th but not 19th century situations-not so much from a historical but strictly a gaming point of view. Perhaps you could combine these two topics. You wrote [above] ...

- The system in GMT's Battles of

Waterloo does not manage itself and if

you have seen A Famous Victory or Fields

of Glory you realize Richard Berg was

really designing a system to manage

early 18th c. battles, for there his system

works.

Kevin Zucker

Mesa, Arizona

For a game's rule system to manage itself, I think four things are necessary. One, the rules must have a logical structure that is paradigmatic for what the educated gamer understands as the flow, for want of a better word, of battle. Such a paradigm is the only possible way for rules to be remembered and the rule book not to become a sort of reference tool.

As corollaries to this proposition are the requirements that the logic be explained and that the exceptions to generally applicable rules also be few and fit into the logical structure. Second, the scale on any game must fit the intent. Only a limited number of factors can be included in a simulation of an event. Failure to understand the relationship between scale and the number of manageable factors results in monster games where regiments or battalions must be micro-managed.

The sophistry that such designs are intended for "team play," one designer suggesting two players per map sheet as a rule, misses the point. If the intent is to simulate a battle the factors that can be effected by the C in C are the ones the player should control. Everything else needs some type of game mechanic to take over the work of micro-management. Third, die rolls need to be multi-purposed so that they do not multiply exponentially. An example would be the use of two colored die, one for each side, to resolve a close combat. Each die could be used for the appropriate side's morale check and either the sum or the use of the tens and ones place could determine the combat result if the attacker "goes in", the defender "stands" and the combat takes place.

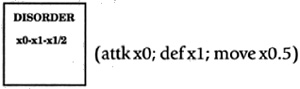

The combat results in such a case should state all the outcomes-leader casualties, retreat losses, morale reductions, etc.-without the need for further die roll or reference to the rules. This leads to corollary four. The Player aids and information markers should aid the player and give hin as much information as can be crammed on a half-inch square. Since game procedures are algorithms (if I remember the definition correctly) an aid like the combat results table needs to contain a sort of visual organizer of the procedure being followe( to resolve combat. In educationese, this kind of presentation is called an advanced organizer, the idea is for the aid to remind the player of the logical procedure he (or sheI've never seen woman play anything this side of Kingmaker) has read in the rules. In the same vein a big "D" is a terrible marke for disorder since it does not give a short hand for the effects.

A counter could look like this at right:

or show the way to get rid of Disorder

(d6>Mri). I have never seen anyone pay

enough attention to information markers

They print "D" and "R" on opposite side

instead of designing a single marker that

informs the player. ... A marker that say

"LIM" conveys nothing. A marker that de

fines what a "maneuver element" can do

when drawn from the cup is an information

marker.

A counter could look like this at right:

or show the way to get rid of Disorder

(d6>Mri). I have never seen anyone pay

enough attention to information markers

They print "D" and "R" on opposite side

instead of designing a single marker that

informs the player. ... A marker that say

"LIM" conveys nothing. A marker that de

fines what a "maneuver element" can do

when drawn from the cup is an information

marker.

Now I've tried to define what I mean but I have probably insulted several designers here; so I really must insist that this little flicker of enlightenment is for your eyes only [gentle readers please take note].

After all can only draw conclusions from experience and that means being critical of design efforts over which people have sweated blood [it's hard enough just to write "D" and "R in blood]. I have never published a design and all I have ever really done is correspond with people who do the job and try to influence them.

Regarding that Alexander game circa 1979, I can outline some features. First, there was the basic assumption that Alexander vs Darius was the equivalent of a World War The game was therefore a simulation of the conquest of the Persian Empire and operated on a strategic level. Because of the nature of the harvest agriculture over most of the area, turns were 2 months long and campaigning was done with the fewest logistical problems during Spring, Summer 1, Fall and Winter 1.

The equivalent to your Center of Ops had to be established ahead of an advance of a main force so it was important to scatter a force throughout productive territory, usually city hexes, send an advanced guard to establish control of an area that could support the whole army and then advance the forces and unite them at just the right season to actively campaign. My ideas were later confirmed by Engels, Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army, and indirectly by Luttwak's Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire.

Another important concept was the Force Pool. Greek mercenaries, Macedonian peasants, Bactrian Horse archers, Cappadocian cavalry-in fact all the combat forces on the board came from Force Pools. Pitched battles rarely eliminated more than one, two or three factors. Real losses were suffered through retreat and a whole army might melt away to return to its force pools where it could be purchased or raised once again. The only way to stop such a process was to occupy territory (like 1776).

Since the Persian's hope for winning rested on the amount of mischief the Phoenician fleet, their Spartan Allies, and Greek mercenaries purchased with the massive reserves of Persian gold could work against Antipater in Greece and the Aegean (there was even a way to get Athens to change sides) there had to be a map for that area on a scale different from the map of the Levant and further Asia.

The importance of Persian gold and Macedonian silver was there; so, Alexander was almost constrained to capture the treasury at Sardis and reduce Phoenicia ASAP to neutralize the Phoenician fleets. If he made it to one of the really massive treasuries like Persepolis or Ecbatana Alexander could usually cause the fall of Darius and had a fighting chance of beating Bessus who almost invariably would succeed.

Most combat was resolved on the basis of numerous die roll modifiers for specialized units and commanders with some units (Cretan Archers) contributing nothing to the odds but just to the die roll. Command bonuses were-Alexander +3, Parmenion Antipater +1, Bessus +2, Memnon +1, Darius 0, the Spartan King +1 and others I cannot remember. Specialized units like companion cavalry, Thessalian Horse Phalanx, Cretan Archers, Bactrian Horse Archers, Immortals, and Athenian Fleet units all had +1 die modifiers. Phocus added +1 to an Athenian fleet combat. I remember it was very important for Antipater to use his silver supply to keep the Athenian fleet paid and operating because Pharnabarzanus could modify the Phoenician fleet by +2. Fleet combat could only take place in coastal hexes and fleets were decomissioned yearly and had to be repaid for and supplied with additional cash for operations every year.

I remember the Persians almost always got a modifier for having a 3-1 (maybe 2-1) superiority in cavalry.

Another feature was the mountain tribes that tended to pop up when an army wanted to cross a mountain pass. The way the rules were written only the Hypaspis, the Cretans, the Agrianians, and the Illyrians (hill folk themselves) could be used to cut through. The Persians had to buy them off; although the Immortals could try to clear the road but there were never more than 2,000 of them (no 10,000 by the time of Darius III).

Important cities had their own intrinsic garrisons, and Tyre was a bitch to take. I forget the name of the Macedonian engineer, but he had a die modifier for siege assaults and could generate "engines" which modified the die even more. You could starve a place out, but that could turn into a race to see how fast attrition from lack of supply would reduce besieger and besieged. Sometimes fortified cities just changed sides, each having a disloyalty die roll modifier. Sidon usually turned coat the moment Alexander got there but Tyre, Halicarnassus & Gaza were pretty resistant to internal revolution. It was impossible for cities to defect if a Persian or Greek Mercenary force (paidup of course) occupied the place. Then they and the citizens fought it out against Alexander. Unwalled cities, like many in the farthest east, were only defended if they had a citadel (sometimes the archaeology on an area was so sparse this fact could not be determined with any accuracy; e.g., Samarkand was walled, I never did get a good answer about Bactra).

After I finished my first thesis and started my thesis in history on Julian's (Caesar 355-360 A.D.) campaign in Gaul I really wanted to switch the design to Julian's reconquest of Gaul in the 350's and to do a tactical game on the Battle of Strasburg. But I'm afraid ten years of teaching Jr. & Sr. High intervened and at one time I was teaching as adjunct faculty at ASU at the same time. So, in the end, I never got back to either Alexander or Julian.

I was reading the rules to Mosby's raiders and suddenly I got one of those flashes of inspiration. Why not a solitaire game on the cruises of the Alabama, Florida, and Shenandoah? I started imagining event decks for each major sea area. A response deck for the ship from which a "hand" could be drawn. And a combat deck for any Union vessels met. I started doing some reading but I have to get a feel for how these raiders operated before I can decide if there is a solitaire simulation there. It's already obvious that the raiders have to worry about coal, repair facilities and supplies some of which must come from prize ships, repair requiring either a jury rig by the ship's engineer or a port in a country willing to bend the diplomatic rules. Maybe there is something there.

Roger L. Pearce

P.S. I ordered 1806. Talk about the need for immediate gratification.

Baltimore, Maryland

What I will ask you is very hard to answer, and that is why I am interested:

In your letter you say "the rules must have a logical structure that is [based upon] the flow ... of battle." I think I understand what you mean, but I would be interested in hearing a more detailed discussion of this point. Your "corollaries" that the logic (or rationale) be explained and that exceptions be few are important enough to be principles in their own right. Also, on your second point, that a limited number of factors can be included, how do you determine these?

My answer would be, first, by reading accounts of the history to be simulated, and hoping that a nice author out there has really comprehended "the flow of battle." Unfortunately, much of military history is just a recounting of events without much attempt to explain why; and those that do us the favor of attempting this often fall down on just that point. So, one is left on one's own resources. Fortunately, we have a wonderful microscope for looking at and seeing all the comers that the historians miss when they focus on what actually did happen.

I call the limit on overcrowding a game with detail the "inside the watch" paradigm, which means that we do not want to open up the watch-case and show the gears turning-all we want to know is the hours and minutes. We do not want to make the player push all those gears around with his finger just to see the hands go around. Basically, for me the single hexagon is analogous to the "watch-case," it is "atomic" in the Greek sense of indivisible and primary. Anything that happens inside the hex cannot, by definition, be shown, and becomes an abstraction inside the players heads. We want the action visible on the map. Of course, there could be a "battle board" that explodes the action of a single hex; that is A by me, because then the action is again invisible in terms of the material components.

Regarding the Alexander game, it sounds like it could stand a lot of simplification. Here (it may be) you know too much and want to put all that in. Could it be that you are suffering from the very "design overload" problem we were just discussing? I read Luttwak's Roman Empire, a classic (though I don't agree with his politics, it is a fine and unique book).

Kevin Zucker

Mesa, Arizona

The question is how one writes rules that follow "the logical flow of battle" i.e., rules that seem intuitive to anyone who reads them.

In the 'real world' battle really has no logical flow. In fact logical structures, paradigms if you will, that we use to describe battle are as employed as surely as any piece of fiction. This observation applies even to the eyewitness account, the "war story" even though I hate the pejorative connotation of that term. Now I could go into a long dissertation on the employment of reality and with some erudition cite theorists in history, literature especially structuralist critics, and psychology all of whose work converge on the central point: Humans emplot reality to make it intelligible.

A wargame/simulation is as much employed view of reality as any. In fact in my original letter I tried to show how games like France '40 and Victory in the West were employed as mechanistic tragedies. Furthermore I suggested that this particular way of plotting the Fall of France comes from Shirer and others who swallow with little critical sense the pontificating of the surviving German participants and the excuses of the French. "Where were our planes? Indeed! Shooting down one-third of the Luftwaffe force engaged and that without radar, plotting rooms, sector stations or any elaborate system to alert aircraft." Since my academic training has demonstrated with some regularity that if a historian's sources have employed the historical experience as a tragedy, the historian will rarely do differently, it is not surprising to me that no simulation of the battle of France has really chosen to buck the trend set by the literature.

All of this leads up to the problem of wargame rules if one just realizes that the rules are really a set of conventions used for writing a "story" of the battle. I hope we all remember boxes that offered us as players the opportunity of "rewriting history." And if you happen to have an old 'AK' box around re-read the cover and you cannot avoid the conclusion that the player is being invited to create a fiction!

Rules, therefore are a sort of list of points upon which the plot can turn. Wargame rules are like the conventions of a Petrarchan sonnet; they don't limit the outcome, only the form.

The best rules keep the outcome in suspense, all things being equal between players, for as long as possible-and as the player reads the rules he has to be able to see how the battle "narrative" could turn out because of the conditional limit to the "plot" mediated by the rule. If the player can understand the possible plots he will remember the rules and they will represent for him the "logical flow of battle. " I would suggest that explaining the reasons for a rule often aids in the process.

I read a game replay in The General of Alexander. Suddenly I was unbeatable, but better yet I had such a firm understanding of the rules, that when my toughest opponent in those days began searching the rules for a way out of his impending defeat I could always tell him what he wanted to know. Further, when War and Peace came out I seemed to get it instinctively because it was on that level of campaigning that I had been reading about. So if the designer reveals his favorite book on what is being simulated, read that book.

Roger L. Pearce

Back to Wargame Design Vol. 2 Nr. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Wargame Design List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Operational Studies Group.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com