When the Communists launched their TET Offensive on 30 January, they struck in force almost everywhere in South Vietnam except Khe Sanh. Their prime targets were not military installations but the major population centers--36 provincial capitals, 64 district capitals, and 5 autonomous cities. The leaders in Hanoi were apparently becoming dissatisfied with their attempts to win in the South by a protracted war of attrition and decided on one massive stroke to tip the scales in their favor.

When the Communists launched their TET Offensive on 30 January, they struck in force almost everywhere in South Vietnam except Khe Sanh. Their prime targets were not military installations but the major population centers--36 provincial capitals, 64 district capitals, and 5 autonomous cities. The leaders in Hanoi were apparently becoming dissatisfied with their attempts to win in the South by a protracted war of attrition and decided on one massive stroke to tip the scales in their favor.

Khe Sanh.

Consequently, the enemy unleashed some 62,000 troops, many of whom infiltrated the cities disguised as civilians, in hopes that they could foster a public uprising against the central government and encourage mass defections among the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces. Virtually all available VC main and local force units were thrown into the initial attacks. With the exception of Hue and Da Nang, NVA units were generally committed a few days later to reinforce the assault troops.(73)

The sudden onslaught initially achieved surprise but, in the final analysis, the overall military effort failed miserably. Allied forces reacted quickly and drove the invaders from the cities and towns, killing approximately 32,000 (as of 11 February) hard-core guerrillas and North Vietnamese soldiers in the process. Many Viet Cong units, with no other orders than to take their initial objectives and hold until reinforcements arrived, were wiped out completely.

Ironically, these elite cadres were the backbone of the guerrilla infrastructure in the South which the Communists, up to that point, had tried so hard to preserve. In Saigon and Hue, die-hard remnants held out for several weeks but, for the most part, the attacks were crushed within a few days. The general uprising and mass desertions never materialized; on the contrary, the offensive tended to galvanize the South Vietnamese. (74)

Even though he paid an exorbitant price, the enemy did achieve certain gains. If the Communists' goal was to create sensational headlines which would stun the American people--they succeeded.

To the strategists in Hanoi, an important byproduct of any military operation was the associated political ramifications in the United States; namely, how much pressure would certain factions put on their leaders to disengage from the struggle in South Vietnam. To the delight of the Communists, no doubt, the TET Offensive had a tremendous psychological impact in the U. S. and, as usual, the response of the dissidents was vociferous.

Much of the reaction was completely out of proportion to the actual military situation but it had a definite demoralizing effect on the American public--the long-range implications of which are still undetermined.(75)

Another casualty of these nation-wide attacks was the pacification program in rural communities. When the Allies pulled back to clear the cities, they temporarily abandoned portions of the countryside to the enemy. Upon return, they found that progress in the so-called "battle for the hearts and minds of the people" had received a temporary set back.(76)

To achieve these ends, however, the enemy troops brought senseless destruction to Vietnamese cities and heaped more suffering upon an already war-weary populace. Thousands of innocent civilians were killed and hundreds of thousands made home less--mostly in Saigon/Cholon and Hue. Four days after the initial attacks, the central government formed the Central Recovery Committee which, with U. S. assistance, launched Project RECOVERY to help alleviate the misery of the people.

Had this program not been implemented, the Communists might have come much closer to achieving their goal of overthrowing the government. In addition to the destruction in the cities, the enemy violated a sacred religious holiday and, what's worse, actually desecrated a national shrine by turning the majestic Hue Citadel into a bloody battlefield. For these acts, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese earned the deep-seated hatred of many South Vietnamese who in the past had been, at best, neutral.(77)

Enemy Objectives

Whether or not Khe Sanh was, in fact, the ultimate enemy objective or merely a diversion for the TET Offensive has not yet been established with certainty. The U. S. command in Saigon believed that the Communists' goal was to create a gener. uprising, precipitate mass defections in the RVN armed forces, and then seize power. The concentration of NVA regular forces in the northern two provinces was primarily to support this overall objective but it was also possible that the enemy had a secondary aspiration of shearing off and seizing the Quang Tri-Thua Thien area should his primary effort fail. Thus Khe Sanh was envisioned as an intregal part of the master plan, or as General Westmoreland called it "an option play."

Subsequent events tended to vindicate that evaluation. Since the initial nation-wide attacks had been conducted primarily by Viet Cong guerrillas and main force units, the NVA regular forces remained relatively unscathed and, with two of the four North Vietnamese divisions known to be in I Corps poised around the 26th Marines, there was little doubt as to where the next blow would fall.

Furthermore, the enemy's extensive preparations around the base reinforced the belief that this effort was a major offensive and not just a feint. Before investing the garrison, the North Vietnamese dug positions for their longrange artillery pieces. Later, they emplaced countless smaller supporting weapons, established numerous supply depots, and began the ant-like construction of their intricate siege-works. This intensive build-up continued long after most of the fighting associated with the TET Offensive was over.(78)

The enemy had much to gain by taking Khe Sanh. If they could seize any portion of Quang Tri Province, the Communists would have a much stronger bargaining position at any future conference table. In addition, the spectre of Dien Bien Phu which was constantly raised in the American press undoubtedly led the enemy to believe that the coming battle could not only prove successful but decisive. If the garrison fell, the defeat might well turn out to be the coup de grace to American participation in the war.

At first, the Marines anticipated a major pitched battle, similar to the one in 1967, but the enemy continued to bide his time and the battle at Khe Sanh settled into one of supporting arms.(79)

At Khe Sanh, the periodic showers of enemy artillery shells were, quite naturally, a major source of concern to General Tompkins and Colonel Lownds and they placed a high priority on the construction of stout fortifications. Understandably, not every newcomer to Khe Sanh immediately moved into a thick bunker or a six-foot trench with overhead cover. The colonel had spent most of his tour with a one-battalion regiment and had prepared positions for that battalion; then, almost overnight, his command swelled to five battalions. The new units simply had to build their own bunkers as quickly as they could.(80)

At Khe Sanh, the periodic showers of enemy artillery shells were, quite naturally, a major source of concern to General Tompkins and Colonel Lownds and they placed a high priority on the construction of stout fortifications. Understandably, not every newcomer to Khe Sanh immediately moved into a thick bunker or a six-foot trench with overhead cover. The colonel had spent most of his tour with a one-battalion regiment and had prepared positions for that battalion; then, almost overnight, his command swelled to five battalions. The new units simply had to build their own bunkers as quickly as they could.(80)

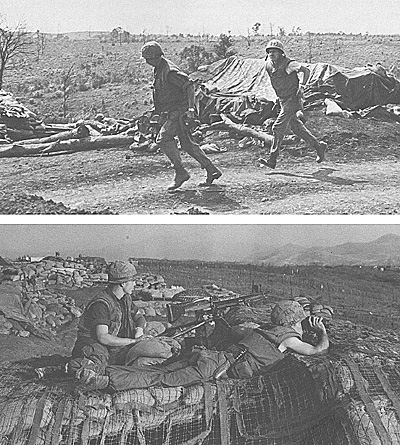

Top: Marines run for cover during artillery and rocket attacks.

Bottom: MG team on top of trench cover while they search for enemy movement.

The regimental commander placed a minimum requirement on his subordinates of providing overhead cover for the troops that would stop, at least, an 82mm mortar round. The FSCC determined that one strip of runway matting and two or three layers of sandbags would fill the requirement. The average bunker usually started as an 8x8 foot dugout with one 6x6 inch timber inserted in each corner and the center for support.

The overhead consisted of planks, a strip of runway matting, sandbags, loose dirt, and more sandbags. Some enterprising Marines piled on more loose dirt, then took discarded 105mm casings and drove them into the top of the bunker like nails. These casings often caused predetonation of the heavier-caliber rounds. The combat engineers attached to the 26th Marines could build one of these bunkers in three or four days; the average infantrymen took longer.

Overhead cover for the trenchlines consisted of a strip of matting placed across the top of the trench at intervals and reinforced with sandbags. The defenders could stand up in the trench during periods of inactivity and duck under the matting when enemy rounds started to fall.(81)

The Marines were also faced with another question concerning their defenses: "How large an artillery round could you defend against and still remain within the realm of practicality?" Since the 26th Marines was supplied solely by air, building material was a prime consideration. Matting and sandbags were easy enough to come by but lumber was at a premium.

Fortifications which could withstand a hit from an 82mm mortar were a must because the North Vietnamese had an ample supply of these weapons but the base was also being pounded, to a lesser degree, by heavier-caliber guns. With the material available to the 26th Marines, it was virtually impossible to construct a shelter that was thick enough or deep enough to stop the heavy stuff.(82)

This fact was borne out when Colonel Lownds decided to build a new regimental CP bunker. The engineers supplied the specifications for an overhead that would withstand a 122mm rocket; to be on the safe side, the colonel doubled the thickness of the roof. The day before the CP was to be occupied, a 152mm round landed squarely on top of the bunker and penetrated both layers.(83)

The massing of enemy artillery made the hill outposts that much more important. Had they been able to knock the Marines from those summits, the North Vietnamese would have been able to fire right down the throats of the base defenders and make their position untenable. As it was, the companies on Hills 881S, 861, 861A, and 553 not only denied the enemy an unobstructed firing platform from which to pound the installation, they also served as the eyes for the rest of the regiment in the valley which eras relatively blind to enemy movement. For observation purposes, Hill 881S was the most strategically located and a discussion of the enemy's heavy weaponry will point out why.

While the 60mm and 82mm mortars were scattered around in proximity of the combat base (roughly within a 2,000-3,000 meter radius), the NVA rocket sites and artillery pieces were located well to the west, southwest, and northwest, outside of friendly counterbattery range.

One particularly awesome and effective weapon was the Soviet-built 122mm rocket, the ballistic characteristics of which had a lot to do with the way the North Vietnamese employed it.

When fired, the projectile was fairly accurate in deflection but, because it was powered by a propellent, the biggest margin of error was in range. Consequently, the North Vietnamese preferred to position their launching sites so the gunners could track along the long axis of a given target; thus, longs and shorts would land "in the ballpark." The KSCB hugged the airstrip and was roughly in the shape of a rectangle with the long axis running east and west.

This made the optimum firing positions for the 122mm rocket either to the east or west of the base on line with the runway. There was really only one logical choice because the eastern site would have placed the rockets within range of the Americans' 175s and extended the enemy's supply lines from Laos.

To the west, Hills 881S or 861 would have been ideal locations because in clear weather those vantage points provided an excellent view of Khe Sanh and were almost directly on line with the airstrip. Unfortunately for the NVA, the Marines had squatters' rights on those pieces of real estate and were rather hostile to claim jumpers. As an alternative, the North Vietnamese decided on 881N but this choice had one drawback since the line of sight between that northern peak and the combat base was masked by the top of Hill 861. Nevertheless, the enemy emplaced hundreds of launching sites along its slopes and throughout the siege approximately 5,000 122mm rockets rained on Khe Sanh from 881N.(84)

Because of their greater range, the enemy's 130mm and 152mm artillery batteries were located even further to the west. These guns were cleverly concealed in two main firing positions. One was on Co Roc Mountain which was southwest of where Route 9 crossed the Laotian border; the other area was 305, so called because it was on a bearing of 305 degrees (west-northwest) from Hill 881S at a range of about 10,000 meters.

While the heavy caliber artillery rounds which periodically ripped into the base were usually referred to as originating from Co Roc, 305 was the source of about 60-70 percent of this fire, probably because it was adjacent to a main supply artery. Both sites were vulnerable' only to air attack and were extremely difficult to pinpoint because of the enemy's masterful job of camouflage, his cautious employment, and the extreme distance from friendly observation posts.

The NVA gunners fired only a few rounds every hour so that continuous muzzle flashes did not betray their positions and, after each round, quickly scurried out to cover the guns with protective nets and screens. Some pieces, mounted on tracks, were wheeled out of caves in Co Roc Mountain, fired, and returned immediately. Though never used in as great a quantity as the rockets and mortars, these shells wreaked havoc at Khe Sanh because there was very little that they could not penetrate; even duds went about four feet into the ground.(85)

The 3/26 elements on Hill 881S were a constant thorn in the enemy's side because the men on that most isolated of the Marine outposts could observe all three of the main NVA firing positions --881N, 305, and Co Roc. When rockets lifted off of 881N or the guns at Co Roc lashed out, the men of Company I could see the flashes and provided advance warning to the base. Whenever possible they directed retaliatory air strikes on the offenders.(*)

(*) One Marine, Corporal Robert J. Arrota, using a PRC-41 UHF radio which put him in direct contact with the attack pilots, personally controlled over 200 air strikes without the aid of a Tactical Air Controller (Airborne); his peers gave him the title of "The Mightiest Corporal In The World."

Whenever the enemy artillery at 305 opened up, the muzzle flashes were hard to see because of the distance and the everpresent dust from air strikes, but the rounds made a loud rustling noise as they arched directly over 881S on the way to Khe Sanh. When the Marines heard the rounds streak overhead, they passed a warning to the base over the 3d Battalion tactical radio net, provided the net was not clogged with other traffic. The message was short and to the point: "Arty, Arty, Co Roc" or "Arty, Arty, 305."(86)

At the base the Marines had devised a crude but effective early warning system for such attacks. Motor transport personnel had mounted a horn from a two-and-a-half ton truck in the top of a tree and the lead wires were attached to two beer can lids. When a message was received from 881S, a Marine, who monitored the radio, pressed the two lids together and the blaring horn gave advanced warning of the incoming artillery rounds.

The radio operator relayed the message over the regimental net and then dived into a hole. Men in the open usually had from five to eighteen seconds to find cover or just hit the deck before "all hell broke loose." When poor visibility obscured the view between 881S and the base, the radio operator usually picked himself up, dusted off, and jokingly passed a three-word message to Company I which indicated that the rounds had arrived on schedule--"Roger India... Splash."(87)

The fact that Company I on 881S was the fly in the enemy's ointment was no secret, especially to the enemy. As a result, North Vietnamese gunners made the Marines' existence there a veritable nightmare. Although no official tally of incoming rounds was recorded, Captain Dabney's position took a much more severe pounding than any of the other hill outposts.

Volume, however, was only part of the story because the incoming was almost always the heavier stuff. The hill received little 60mm or 82mm mortar fire but a deluge of 120mm mortar and 100mm artillery rounds. There was also a smattering of 152mm shells from Co Roc. The shelling was the heaviest when helicopters made resupply runs.

The firing position which plagued the Marines the most was located to the southwest of the hill in a U-shaped draw known as "the Horseshoe." There were at least two NVA 120mm mortars in this area which, in spite of an avalanche of American bombs and artillery shells, were either never 'knocked out or were frequently replaced. These tubes were registered on the hill and harassed Company I constantly. Anyone caught above ground when one of the 120s crashed into the perimeter was almost certain to become a casualty because the explosion produced an extremely large fragmentation pattern.

Captain Dabney figured that it took one layer of runway matting, eight of sandbags, and one of either rocks or 105mm casings to prevent penetration of a 120mm with a quick fuze--nothing the Marines had on 881S could stop a round with a delayed fuze. Because of the shape of the hill, the summit was the only defendable terrain and thus provided the enemy with a compact target; this often resulted in multiple casualties when the big rounds landed within the perimeter.

The only thing that the Marines had going for them was that they could frequently spot a tell-tale flash of an artillery piece or hear the "thunk" when a mortar round left the tube but the heavy shells took their toll. On Hill 881S alone, 40 Marines were killed throughout the siege and over 150 were wounded at least once.(88)

Considering the sheer weight of the bombardment, enemy shells caused a relatively small number of fatalities at the base. Besides the solid fortifications, there were two factors which kept casualties to a minimum.

The first was the flak jacket--a specially designed nylon vest reinforced with overlapping fiberglass plates. The jacket would not stop a highvelocity bullet but it did protect a man's torso and most vital organs against shell fragments. The bulky vest was not particularly popular in hot weather when the Marines were on patrol but in a static, defensive position the jacket was ideal.

The second factor was the high quality of leadership at platoon and company level. Junior officers and staff noncommissioned officers (NCOs) constantly moved up and down the lines to supervise the younger, inexperienced Marines, many of whom had only recently arrived in Vietnam. The veteran staff NCOs, long known as the "backbone of the Corps," knew from experience that troops had to be kept busy. A man who was left to ponder his problems often developed a fatalistic attitude that could increase his reaction time and decrease his life time.

The crusty NCOs did not put much stock in the old cliche: "If a round has your name on it, there's nothing you can do." Consequently, the Marines worked; they dug trenches, filled sandbags, ran for cover, and returned to fill more sandbags. Morale remained high and casualties, under the circumstances, were surprisingly low.(89)

Not Much of a Siege

Although the NVA encircled the KSCB and applied constant pressure, the defenders were never restricted entirely to the confines of the perimeter. The term "siege," in the strictest sense of the word, was somewhat of a misnomer because the Allies conducted a number of daily patrols, often as far as 500 meters from their own lines,(*)(90)

(*) Lieutenant Colonel Mitchell, whose battalion held the rock quarry perimeter, later commented that his troops patrolled out to 1,200 meters. The units at the base never went that far until the siege was lifted.

These excursions were primarily for security and reconnaissance purposes since General Tompkins did not want his men engaged in a slugging match with the enemy outside the defensive wire. If the North Vietnamese were encountered, the Marines broke contact and withdrew, while supporting arms were employed.(91)

One vital area was the drop zone. When the weather turned bad in February, the KSCB was supplied primarily by parachute drops. Colonel Lownds set up his original zone inside the FOB-3 compound but later moved it several hundred meters west of Red Sector because he was afraid that the falling pallets might injure someone. Lieutenant Colonel Mitchell's 1/9 was given responsibility for security of the drop zone and his patrols conducted daily sweeps along the periphery of the drop area to flush out enemy troops who might try to disrupt the collection of supplies.

In addition, combat engineers swept through the zone each morning and cleared out any mines the enemy set in during the night. Thus the defenders at Khe Sanh were never completely hemmed-in, but the regimental commander admitted that any expedition beyond sight of the base was an invitation to trouble. (92)

The Allies did more than prepare defenses and conduct patrols because the NVA launched three of its heaviest ground attacks during the first week in February. In the pre-dawn hours of 5 February, the North Vietnamese lashed out at the Marine base and adjacent outposts with nearly 200 artillery rounds while a battalion from the 325C NVA Division assaulted Hill 861A. Colonel Lownds immediately placed all units on Red Alert and, within minutes, 1/13 was returning fire in support of E/2/26.

The fight on Hill 861A was extremely bitter. At 0305 the North Vietnamese opened up on Captain Breeding's positions with a tremendous 82mm mortar barrage. This was followed by continuous volleys of RPG rounds which knocked out several Marine crew-served weapons and shielded the advance of the NVA sappers and assault troops. The North Vietnamese blew lanes through the barbed wire along the northern perimeter and slammed into the Company E lines.

Second Lieutenant Donald E. Shanley's 1st Platoon bore the brunt of the attack and reeled back to supplementary positions. Quickly the word filtered back to the company CP that the enemy was inside the wire and Captain Breeding ordered that all units employ tear gas in defense but the North Vietnamese were obviously "hopped up" on some type of narcotic and the searing fumes had very little effect. Following the initial assault there was a brief lull in the fighting.

The NVA soldiers apparently felt that, having secured the northernmost trenchline, they owned the entire objective and stopped to sift through the Marine positions for souvenirs. Magazines and paperbacks were the most popular. Meanwhile, the temporary reversal only served to enrage the Marines. Following a shower of grenades, Lieutenant Shanley and his men -charged back into their original positions and swarmed all over the surprised enemy troops.(93)

The counterattack quickly deteriorated into a melee that resembled a bloody, waterfront barroom brawl--a style of fighting not completely alien to most Marines. Because the darkness and ground fog drastically reduced visibility, hand-to-hand combat was a necessity. Using their knives, bayonets, rifle butts, and fists, the men of the 1st Platoon ripped into the hapless North Vietnamese with a vengeance. Captain Breeding, a veteran of the Korean conflict who had worked his way up through the ranks, admitted that, at first, he was concerned over how his younger, inexperienced Marines would react in their first fight.

As it became so hot that they actually glowed in the dark.(*)

(*) The men of Company I used the same methods to cool the mortar tubes that they used during the attack against 861 on 21 January.

Again, the bulk of the heavy artillery fire, along with radar controlled bombing missions, was placed on the northern avenues leading to the hill positions. The enemy units, held in reserve, were thus shredded by the bombardment as they moved up to continue the attack.(96)

After the second assault fizzled out, the North Vietnamese withdrew, but enemy gunners shelled the base and outposts through; out the day. At 1430, replacements from 2/26 were helilifted to Hill 861A. Captain Breeding had lost seven men, most of whom were killed in the opening barrage, and another 35 were med-evaced so the new arrivals brought E/2/26 back up to normal strength.

On the other hand, the NVA suffered 109 known dead; many still remained in the 1st Platoon area where they had been shot, slashes or bludgeoned to death.

As near as Captain Breeding could tell, he did not lose a single man during the fierce hand-to-hand struggle; all American deaths were apparently the result of the enemy's mortar barrage and supporting fire. The Marines never knew how many other members of the 325C_ NVA Division had fallen as a result of the heavy artillery and air strikes but the number, was undoubtedly high. All in all, it had been a bad day for the Communists.(97)

The North Vietnamese took their revenge in the early morning hours of 7 February; their victims were the defenders of the Special Forces camp at Lang Vei. At 0042, an American advisor reported that the installation was under heavy attack by enemy tanks. This was the first time that the NVA had employed its armor in the south and, within 13 minutes, 9 PT-76 Soviet-built tanks churned through the defensive wire, rumbled over the antipersonnel minefields, and bulled their way into the heart of the compound.(**)(98)

(**) The defenders later reported knocking out at least one and probably two tanks with rocket launchers.

A battalion from the 66th Regiment, 304th NVA Division, equipped with satchel charges, tear gas, and flamethrowers, followed with an aggressive infantry assault that was coordinated with heavy attacks by fire on the 26th Marines. Colonel Lownds placed the base on Red Alert and the FSCC called in immediate artillery and air in support of the beleaguered Lang Vei garrison. Although the Marines responded quickly, the defensive fires had little effect because, by that time, the enemy had overrun the camp.(*)(99)

(*) The 26th Marines FSCC had prepared extensive defensive fire plans for the Lang Vei Camp. In the early stages of the attack, the camp commander did not request artillery and later asked for only a few concentrations. He never asked for the entire schedule to be put into effect.

The defenders who survived buttoned themselves up in bunkers and, at 0243, called for artillery fire to dust off their own positions.(100)

Lieutenant Colonel Hennelly's artillerymen responded with scores of deadly air bursts which peppered the target area with thousands of fragments. The 1/13 batteries fired over 300 rounds that morning and the vast fire superiority was echoed in the radio transmission of one Lang Vei defender who said: "We don't know what you're using but for God's sake keep it up." That was one of the last transmissions to Khe Sanh because, at 0310, the Marines lost communications with the camp.(101).

Part of Colonel Lownds' mission as coordinatorr of all friendly forces in the Khe Sanh area was to provide artillery support for Lang Vei and, if possible, to reinforce the camp in case of attack. Under the circumstances, a relief in strength was out of the question. In early January, when M/3/26 was in reserve, Lieutenant Colonel Alderman and Major Caulfield had conducted a personal reconnaissance of Route 9 between the KSCB and Lang Vei to determine the feasibility of moving a large unit overland.

Their opinion was that any such attempt would be suicidal because the terrain bordering Route 9 was so well suited for an ambush it was an "NVA dream."

Any column moving down the road, especially at night, would undoubtedly have been ambushed.(**) (102)

(**) Documents taken off a dead NVA officer later in the battle indicated that the enemy hoped that the attack on Lang Vei would draw the Marines out of Khe Sanh so he could destroy the relief column.

If the Marines went directly over the mountains, they would have to hack through the dense growth and waste precious hours.(***) (103)

(***) In November 1967, Lieutenant Colonel Wilkinson, on direction of the regimental commander, had sent a rifle company to determine possible direct routes through the jungle. The company commander, Captain John N. Raymond, reported that his unit, avoiding well used trails to preclude ambush, had made the trip in about 19 hours.

A large-scale heliborne effort was ruled out because the North Vietnamese apparently anticipated such a move and withdrew their tanks to the only landing zones near the camp which were suitable for such an operation. Even with tactical aircraft providing suppressive fire, a helo assault into the teeth of enemy armor was ill-advised. The most important factor, however, was that NVA units in the area greatly outnumbered any force Colonel Lownds could commit. (104)

Hit and Run Rescue

Since a relief in force was undesirable, plans for a hit and run rescue attempt were quickly drawn up at General Cushman's headquarters. Once General Westmoreland had given the green light, Major General Norman J. Anderson, commanding the 1st MAW and Cclonel Jonathan F. Ladd of the U. S. Army Special Forces, worked out the details. Two major points agreed upon were that the helicopters employed in the operation would be those which were not essential to the 26th Marines at the moment and that Marine fixed-wing support would be provided.(105)

As soon as it was light, the survivors of the Lang Vei garrison managed to break out of their bunkers and work their way to the site of an older camp some 400-500 meters to the east. Later that same day, a raiding party composed of 40 CIDG personnel and 10 U. S. Army Special Forces advisors from FOB-3 boarded Quang Tri-based MAG-36 helicopters and took off for Lang Vei. A flight of Huey gunships, led by Lieutenant Colonel William J. White, Commanding Officer of Marine Observation Squadron 6, as well as jet aircraft escorted the transport choppers. While the jets and Hueys covered their approach, the helicopters swooped into a small strip at the old camp and took on survivors, including 15 Americans.

In spite of the heavy suppressive fire provided by the escorts, three transport helos suffered battle damage during the evacuation. One overloaded chopper, flown by Captain Robert J. Richards of Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 262, had to make the return trip to Khe Sanh at treetop level because the excess weight prevented the pilot from gaining altitude.(106)

(*) On the return trip to the KSCB, Captain Richards flew over the outskirts of Khe Sanh Village. A NVA soldier suddenly stepped out of one hut and sprayed the low-flying chopper with a burst from his AK-47 assault rifle. The rounds ripped out part of Richards' instrument panel and one bullet zinged about two inches in front of his nose before passing through the top of the cockpit. A Marine gunner on the CH-46 quickly cut down the North Vietnamese but the damage had already been done. Even though he was shaken by the experience, the pilot nursed his crippled bird back to the base and landed safely. Once on the ground, he quickly switched helicopters and returned to Lang Vei for another evacuation mission. For his actions during the day, Captain Richards was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

There was a large number of indigenous personnel--both military and civilian--who could not get out on the helicopters and had to move overland to Khe Sank, A portion of these were members of the Laotian Volunteer Battalion 33 which on 23 January had been overrun at Ban Houei San, Laos (near the Laotian/ South Vietnam border) by three NVA battalions.

The remnants fled across the border and took refuge at Lang Vei and when the Special Forces camp fell, the Laotians continued their trek to the east with a host of other refugees. At 0800 on the 8th, about 3,000 approached the southern perimeter at Khe Sanh and requested admittance. Colonel Lownds, fearing that NVA infiltrators were in their midst, denied them entrance until each was searched and processed.

This took place near the FOB-3 compound after which some of the refugees were evacuated. The Laotians were eventually returned to their own country.(107)

Also on the morning of 8 February, elements of the 101D Regiment, 325C Division launched the first daylight attack against the 26th Marines. At 0420, a reinforced battalion hit the 1st Platoon, A/1/9, which occupied Hill 64 some 500 meters west of the 1/9 perimeter. Following their usual pattern, the North Vietnamese tried to disrupt the Marines' artillery support with simultaneous bombardment of the base.

To prevent friendly reinforcements from reaching the small hill the enemy also shelled the platoon's parent unit and, during the fight, some 350 mortar and artillery rounds fell on the 1/9 positions. The NVA assault troops launched a two-pronged attack against the northwestern and southwestern corners of the A/1/9 outpost and either blew the barbed wire with bangalore torpedoes or threw canvas on top of the obstacles and rolled over them. The enemy soldiers poured into the trenchline and attacked the bunkers with RPGs and satchel charges. They also emplaced machine guns at the edge of the penetrations and pinned down those Marines in the eastern half of the perimeter who were trying to cross over the hill and reinforce their comrades.(108)

The men in the northeastern sector, led by the platoon commander, Second Lieutenant Terence R. Roach, Jr., counterattacked down the trenchline and became engaged in savage hand-to-hand fighting. While rallying his troops and directing fire from atop an exposed bunker, Lieutenant Roach was mortally wounded. From sheer weight of numbers, the North Vietnamese gradually pushed the Marines back until the enemy owned the western half of the outpost. At that point, neither side was able to press the advantage. Pre-registered mortar barrages from 1/9 and artillery fire from the KSCB had isolated the NVA assault units from any reinforcements but at the same time the depleted 1st Platoon was not strong enough to dislodge the enemy.(109)

One Marine had an extremely close call during the fight but lived to tell about it. On the northern side of the perimeter, Private First Class Michael A. Barry of the 1st Squad was engaged in a furious hand grenade duel with the NVA soldiers when a ChiCom grenade hit him on top of the helmet and landed at the young Marine's feet. PFC Barry quickly picked it up and drew back to throw but the grenade went off in his hand. Had it been an American M-26 grenade, the private would undoubtedly have been blown to bits but ChiCom grenades frequently produced an uneven frag pattern.

In this case, the bulk of the blast went down and away from the Marine's body; Barry had the back of his right arm, his back, and his right leg peppered with metal fragments but he did not lose any fingers and continued to function for the rest of the battle.(110)

In another section of the trenchline, Lance Corporal Robert L. Wiley had an equally hair-raising experience. Wiley, a shell shock victim, lay flat on his back in one of the bunkers which had been overrun by the enemy. His eardrums had burst, he was temporarily paralyzed and his glazed eyes were fixed in a corpse like stare but the Marine was alive and fully aware of what was going on around him.

Thinking that Wiley was dead, the North Vietnamese were only interested in rummaging through his persona effects for souvenirs. One NVA soldier found the Marine's wallet and took out several pictures including a snapshot of his family gathered around a Christmas tree. After pocketing their booty, the North Vietnamese moved on; Lance Corporal Wiley was later rescued by the relief column.(111)

At 0730, Lieutenant Colonel Mitchell committed a second platoon, headed by the Company A commander, Captain Henry J. M. Radcliffe, to the action. By 0900, the relief force had made its way to the eastern slope of the small hill and established contact with the trapped platoon.

During the advance, Companies B and D, along with one section of tanks, delivered murderous direct fire to the flanks and front of Captain Radcliffe's column, breaking up any attempt by the enemy to interdict the linkup.

After several flights of strike aircraft had pasted the reverse slope of the hill, the company commander led his combined forces in a frontal assault over the crest and, within 15 minutes, drove the North Vietnamese from the outpost. Automatic weapons chopped down many North Vietnamese as they fled from the hill. The battered remnants of the enemy force retreated to the west and, once in the open, were also taken under fire by the rest of the Marine battalion.

In addition, the artillery batteries at KSCB contributed to the slaughter and, when the smoke cleared, 150 North Vietnamese were dead. Although the platoon lines were restored, Colonel Lownds decided to abandon the position and, at 1200, the two units withdrew with their casualties. Marine losses that morning on the outpost were 21 killed and 26 wounded; at the base, 5 were killed and 6 wounded.(112)

During the next two weeks, the NVA mounted no major ground attack but continued to apply pressure on the KSCB. There were daily clashes along the Marine lines but these were limited to small fire fights, sniping incidents, and probes against the wire. A decrease in activity along the various infiltration routes indicated that the enemy had completed his initial buildup and was busily consolidating positions from which to launch an all-out effort.

The Allies continued to improve their defenses and by mid-February most units occupied positions with three or four layers of barbed wire, dense minefields, special detection devices, deep trenches, and mortar-proof bunkers. The battle reverted to a contest of supporting arms and the North Vietnamese stepped up their shelling of the base, especially with direct fire weapons. Attempts to silence the enemy guns were often frustrated because the Marines were fighting two battles during February--one with the NVA, the other with the weather. (113)

Back to Table of Contents -- US Marines: Khe Sanh

Back to Vietnam Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com