With the beginning of the new year, Khe Sanh again became the focal point of enemy activity in I Corps. All evidence pointed to a North Vietnamese offensive similar to the one in 1967, only on a much larger scale. From various intelligence sources, the III MAF, 3d Marine Division, and 26th Marines Headquarters learned that NVA units, which usually came down the "Santa Fe Trail" and skirted the combat base outside of artillery range, were moving into the Khe Sanh area and staying.(*)(33)

With the beginning of the new year, Khe Sanh again became the focal point of enemy activity in I Corps. All evidence pointed to a North Vietnamese offensive similar to the one in 1967, only on a much larger scale. From various intelligence sources, the III MAF, 3d Marine Division, and 26th Marines Headquarters learned that NVA units, which usually came down the "Santa Fe Trail" and skirted the combat base outside of artillery range, were moving into the Khe Sanh area and staying.(*)(33)

(*) The Santa Fe Trail is a branch of the Ho Chi Minh Trail which closely parallels the South Vietnam/Laos border.

At first, the reports showed the influx of individual regiments, then a division headquarters; finally a front headquarters was established indicating that at least two NVA divisions were in the vicinity. In fact, the 325C NVA Division had moved back into the region north of Hill 881N while a newcomer to the area, the 304th NVA Division, had crossed over from Laos and established positions southwest of the base. The 304th was an elite home guard division from Hanoi which had been a participant at Dien Bien Phu.(**)(34)

Top: Five M-48 tanks of the 3rd Tank Bttn add their 90mm guns to the defense of the combat base.

Bottom: Two Ontos platoons of 3rd Anti-tank Bttn were at Khe Sanh. Each sports six 106mm recoiless rifles with co-axial mounted 50-caliber spotting rifles.

(**) In addition, one regiment of the 324th Division was located in the central DMZ some 10-15 miles from Khe Sanh and maintained a resupply role. In the early stages of the siege, the presence of the 320th Division was confirmed north of the Rockpile within easy reinforcing distance of Khe Sanh; thus, General Westmoreland and General Cushman were initially faced with the possibility that Khe Sanh would be attacked by three divisions plus a regiment. General Tompkins, however, kept constant pressure on these additional enemy units and alleviated their threat.

The entire force included six infantry regiments, two artillery regiments, an unknown number of tanks, plus miscellaneous support and service units.

Enemy Shift

Gradually, the enemy shifted his emphasis from reconnaissance and harassment to actual probes and began exerting more and more pressure on Allied outposts and patrols. One incident which reinforced the belief that something big was in the wind occurred on 2 January near a Marine listening post just outside the main perimeter.(35)

The post was located approximately 400 meters from the western end of the airstrip and north of where the Company L, 3/26 lines tied in with those of 1/26.. At 2030, a sentry dog was alerted by movement outside the perimeter and a few minutes later the Marines manning the post reported that six unidentified persons were approaching the defensive wire.

Oddly enough, the nocturnal visitors were not crawling or attempting to hide their presence; they were walking around as if they owned the place. A squad from L/3/26, headed by Second Lieutenant Nile B. Buffington, was dispatched to investigate. Earlier in the day the squad had rehearsed the proper procedure for relieving the listening post and had received a briefing on fire discipline. The training was shortly put to good use.

Lieutenant Buffington saw that the six men were dressed like Marines and, while no friendly patrols were reported in the area, he challenged the strangers in clear English to be sure. There was no reply. A second challenge was issued and, this time, the lieutenant saw one of the men make a motion as if going for a hand grenade.

The Marines opened fire and quickly cut down five of the six intruders. One enemy soldier died with his finger inserted in the pin of a grenade. The awesome hitting power of the M-16 rifle was quite evident since all five men were apparently dead by the time they hit the ground. The lone survivor was wounded but managed to escape after retrieving some papers from a mapcase which was on one of the bodies. Using a sentry dog, the Marines followed a trail of blood to the southwest but gave up the hunt in the darkness. The direction the enemy soldier was heading led the Marines to believe that his unit was located beyond the rock quarry.

The importance of the contact was not realized until later when intelligence personnel discovered that all five of the enemy dead were officers including an NVA regimental commander, operations officer, and communications officer. The fact that the North Vietnamese would commit such key men to a highly dangerous, personal reconnaissance indicated that Khe Sanh was back at the top of the Communists' priority list.(36)

This series of events did not go unnoticed at higher headquarters. General Cushman saw that Colonel Lownds had more on his hands than could be handled by two battalions and directed that 2/26 be transferred to the operational control of its parent unit. On 16 January, 2/26, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Francis J. Heath, Jr., landed at the Khe Sanh Combat Base; its arrival marked the first time that the three battalions of the 26th Marines had operated together in combat since Iwo Jima.

The rapid deployment of Lieutenant Colonel Heath's unit was another example of the speed with which large number of troops could be committed to battle. The regimental commander knew that he would be getting reinforcements but he did not know exactly when they would arrive; he was informed by telephone just as the lead transports were entering the landing pattern. The question that then arose was: "Where could the newcomers do the most good?"(37)

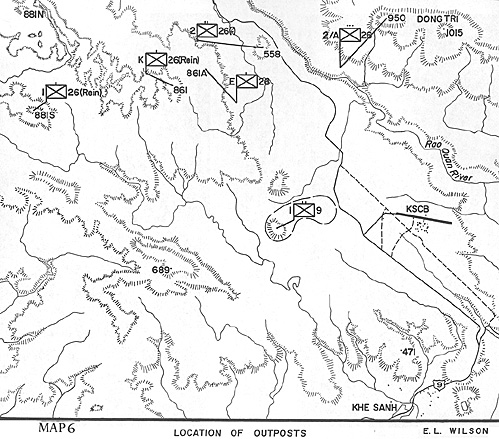

Outside of the combat base itself, there were several areas which were vital. The most critical points were the hill outposts, because both General Tompkins and Colonel Lownds were well aware of what had happened at Dien Bien Phu when the Viet Minh owned the mountains and the French owned the valley. It was essential that the hills around Khe Sanh remain in the hands of the Marines. Shortly after its arrival in mid-December 1967, 3/26 had relieved 1/26 of most of this responsibility. Company I, 3/26, along with a three-gun detachment of 105mm howitzers from Battery C, 1/13, was situated atop Hill 881S; Company K, 3/26, with two 4.2-inch mortars, was entrenched on Hill 861; and the 2d Platoon, A/l/26 defended the radio-relay site on Hill 950. This arrangement still left the NVA with an excellent avenue of approach through the Rao Quan Valley which runs between Hills 861 and 950. The regimental commander decided to plug that gap with the newly arrived 2d Battalion,(38)

At 1400 the day it arrived, Company F, 2/26, conducted a tactical march to Hill 558--a small knob which sat squarely in the middle of the northwestern approach. The rest of the battalion spent the night in an assembly area approximately 1,300 meters west of the airstrip. The following day, Lieutenant Colonel Heath moved his three remaining companies and the CP group overland to join Company F. Once the Marines were dug in, the perimeter completely encompassed Hill 558 and blocked enemy movement through the Rao Quan Valley.(39)

Even with 2/26 in position, there was still a flaw in the northern screen. The line of sight between K/3/26, on Hill 861, and 2/26 was masked by a ridgeline which extended from the summit of 861 to the northeast. This stretch of high ground prevented the two units from supporting each other by fire and created a corridor through which the North Vietnamese could maneuver to flank either Marine outpost.

About a week after his arrival on Hill 558, Captain Earle G, Breeding was ordered to take his company, E/2/26, and occupy the finger at a point approximately 400-500 meters northeast of K/3/26. From this new vantage point, dubbed Hill 861A, Company E blocked the ridgeline and was in a good position to protect the flank of 2/26. Because of its proximity to K/3/26, Company E, 2/26, was later transferred to the operational control of the 3d Battalion. Although these units did not form one continuous defensive line, they did occupy the 'key terrain which overlooked the valley floor.(40)

With the primary avenue of approach blocked, Colonel Lownds utilized his remaining assets to provide base security and conduct an occasional search and destroy mission. The lst Battalion was given the lion's share of the perimeter to defend with lines that extended around three sides of the airstrip. Lieutenant Colonel Wilkinson's Marines occupied positions that paralleled the runway to the north (Blue Sector), crossed the eastern end of the strip, and continued back to the west along the southern boundary of the base (Grey Sector).

The southwestern portion of the compound was manned by Forward Operating Base-3 (FOB-3), a conglomeration of indigenous personnel and American advisors under the direct control of a U. S. Army Special Forces commander. FOB-3 tied in with 1/26 on the east and L/3/26 on the west. Company L, 3/26, was responsible for the northwestern section (Red Sector) of the base and was thinly spread over approximately 3,000 meters of perimeter. The remaining company from the 3d Battalion, M/3/26, was held in reserve until 19 January when two platoons and a command group were helilifted to 881S.

Even though it held a portion of the perimeter, Company D, 1/26 became the reserve and the remaining platoon from M/3/26 also remained at the base as a reaction force.(*)(41)

(*) On the 21st, a platoon from A/1/26 reinforced K/3/26 on Hill 861 and a second platoon from Company A later followed suit. Throughout most of the siege the line up on the hill outpost remained as follows: Hill 881S--Company I, 3/26 plus two platoons and a command group from Company M 3/26; Hill 861--Company K, 3/26 plus two platoons from Company A, 1/26; Hill 861A--Company E, 2/26; Hill 558--2/26 (minus the one company on 861A); Hill 950--one platoon from 1/26.

In addition to his infantry units, the regimental commander had an impressive array of artillery and armor. Lieutenant Colonel John A. Hennelly's 1/13 provided direct support for the 26th Marines with one 4.2-inch mortar battery, three 105mm howitzer batteries, and one provisional 155mm howitzer battery (towed). The 175mm guns of the U. S. Army's 2d Battalion, 94th Artillery at Camp Carroll and the Rockpile were in general support. Five 90mm tanks from the 3d Tank Battalion, which had been moved to Khe Sanh before Route 9 was cut, were attached to the 26th Marines along with two Ontos platoons from the 3d Antitank Battalion.(*)

(*) The Ontos is a lightly armored tracked vehicle armed with six 106mm recoilless rifles. Originally designed as a tank killer, it is primarily used in Vietnam to support the infantry.

These highly mobile tracked vehicles could be rapidly mustered at any threatened point so Colonel Lownds generally held his armor in the southwestern portion of the compound as a back-up for L/3/26 and FOB-3. All told, the Khe Sanh defenders could count on fire support from 46 artillery pieces of varied calibers, 5 90mm tank guns, and 92 single or Ontos-mounted 106mm recoilless rifles. With an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 North Vietnamese lurking in the surrounding hills, the Marines would need it all.(42)

Deja Vu Ambushes

Deja Vu Ambushes

Ironically, the incidents which heralded the beginning of full-scale hostilities in 1968 occurred in the same general area as the encounter which touched off tha heavy fighting in 1967. On 19 January 1968, the 3d Platoon, 1/3/26 was patrolling along a ridgeline 700 meters southwest of Hill 881N where, two days before, a Marine reconnaissance team had been ambushed.

Ambush near Hill 881N on Jan. 17 1968 was a prelude to the opening battle three days later.

The team leader and radioman were killed and, while the bodies had been recovered, the radio and a coded frequency card were missing. The 3d Platoon was scouring the ambush site for these items when it was taken under fire by an estimated 25 NVA troops. The Marines returned fire, then broke contact while friendly artillery plastered the enemy positions.

The next morning, Company I, commanded by Captain William H. Dabney, returned to the scene in force. The captain actually had two missions: first, to try and make contact with the enemy, and, second, to insert another reconnaissance team in the vicinity of the ambush site. Two platoons and a command group from Company M, 3/26, commanded by Captain John .J. Gilece, Jr. were helilifted to 881S and manned the perimeter while Company I moved out to the north.(**)

(**) Captain Gilece was wounded by sniper fire and on 1 February, First Lieutenant John T. Esslinger, the executive officer, assumed command.

The terrain between 881S and its northern twin dropped off into a deep ravine and then sloped gradually upward to the crest of 881N. The southern face of 881N had two parallel ridgelines about 500 meters apart which ran up the hill and provided the company with excellent avenues of approach. These two fingers were dotted with a series of small knobs which Captain Dabney had designated as intermediate objectives.

The Marines moved out at 0500 proceeding along two axes with the 1st and 2d Platoons on the left ridgeline and the 3d Platoon on the right. The ground fog was so thick that the men groped along at a snail's pace probing to their front with extended rifles much the same way a blind man uses a walking cane. For that reason, Captain Dabney had placed Second Lieutenant Harry F. Fromme's 1st Platoon and Second Lieutenant Thomas D. Brindley's 3d Platoon in the lead because both units had patrolled this area frequently and the commanders knew the terrain like the back of their hands. In spite of this, by 0900 the entire force had covered only a few hundred meters but then the fog began to lift enabling the Marines to move out at a brisker pace. The company swept out of the draw at the northern base of 881S, secured its first intermediate objective without incident, and then advanced toward a stretch of high ground which was punctuated by four innocent-looking little hills. These formed an east-west line which ran perpendicular to and bisected the Marines' intended route of march. As it turned out this area was occupied by elements of an NVA battalion and each mound was a link in a heavily-fortified defensive chain.(43)

As the element on the right moved forward after a precautionary 105mm artillery concentration, the enemy opened up with small arms, .50 caliber machine guns, and grenade launchers (RPGs). The resistance was so stiff that Captain Dabney ordered Lieutenant Brindley to hold up his advance and call for more artillery while the force on the left pushed forward far enough to place flanking fire on the NVA position. The 1st and 2d Platoons, however, fared no better; volleys of machine gun fire from the other enemy-owned hills cut through the Marine ranks like giant scythes and, in less than 30 seconds, 20 men were out of action, most with severe leg wounds. Caught in a cross fire, the captain ordered Fromme to hold up and evacuate his wounded. Again, Lieutenant Brindley's men on the right surged forward in the wake of 155mm prep fires. The assault, as_ described by one observer, was like a "page out of /the life of/ Chesty Puller."(*)

(*) Lieutenant General Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller, a legendary figure in Marine Corps history, is the only Marine to have won the Navv Cross five times.

Brindley was everywhere; he moved from flank to flank slapping his men on the back and urging them on. The lieutenant led his platoon up the slope and was the first man on top of the hill but, for him, the assault ended there--he was cut down by a sniper bullet and died within minutes.(*)

(*) Lieutenant Brindley was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross.

During the advance, the recon team, which had volunteered to join the attack, veered off to the right into a small draw and became separated from the rest of the platoon. When the enemy troops were finally driven off the hill, they fled to the east and inadvertently smashed headlong into the isolated team. After a brief but savage fight, the North Vietnamese overran the team and made good their escape; most of the recon Marines were seriously wounded and lay exposed to direct fire from the enemy on the easternmost hill. Several other man in the 3d Platoon were hit during the wild charge and by the time the objective had been taken, the radioman--a corporal--discovered that he was the senior man in the platoon. He quickly reported that fact to Captain Dabney.

The company commander saw that the enemy defense hinged on the center hill which the 3d Platoon had just taken. If he could consolidate that objective, Dabney would have a vantage point from which to support, by fire, assaults on the other three NVA positions. Second Lieutenant Richard M. Foley, the Company I Executive Officer, had moved up to take command of the 3d Platoon and he reported that while the unit had firm possession of the hill, there were not enough men left to evacuate the casualties. In addition, he could not locate the recon team and his ammunition was running low.

Dabney, therefore, ordered Lieutenant Fromme's 1st Platoon to remain in place and support the left flank of the 3d Platoon by fire. With Second Lieutenant Michael H. Thomas' 2d Platoon which had been in reserve on the left, the company commander pulled back to the south, hooked around to the east and joined Foley's unit on its objective. The officers tried to evacuate the wounded and reorganize but this attempt was complicated by the fact that one half of the hastily formed perimeter was being pelted by .50 caliber machine gun and sniper fire from the enemy's easternmost position.

Heroism

At this point, there were two acts of extraordinary heroism. Lieutenant Thomas, who was crouched in a crater alongside the company commander, was informed of the wounded recon Marines who lay in the open at the eastern base of the hill. Even though it was courting certain death to do so, Thomas jumped out of the hole without hesitation and started down the hill. He had only gotten a few steps when an enemy sniper shot him through the head killing him instantly.(*)

(*) For his actions throughout the battle, Lieutenant Thomas was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross.

In spite of what happened to the lieutenant, Sergeant Daniel G. Jessup quickly followed his lead. While the NVA hammered away at the exposed slope with continuous machine gun and sniper fire, the sergeant slithered over the crest and crawled down the hill to locate the recon unit. Once at the bottom, he found the team in a small saddle which was covered with elephant grass; two of the Marines were dead and five were seriously wounded. Jessup hoisted one of the wounded men onto his back and made the return trip up the fireswept slope.

Gathering up a handful of Marines, the sergeant returned and supervised the evacuation of the entire team. When all the dead and wounded had been retrieved, Jessup zig-zagged down the hill a third time to gather up weapons and insure that no one had been left behind. For his calm courage and devotion to his comrades, Sergeant Jessup was later awarded the Silver Star for heroism.

The heavy fighting raged throughout the afternoon. Lieutenant Colonel Alderman, his operations officer, Major Matthew P. Caulfield, and representatives of the Fire Support Coordination Center (FSCC) flew from Khe Sanh to X11 11 881S by helicopter so they could personally oversee the battle. During the action, Company I drew heavy support from the recoilless rifles, mortars, and 105mm howitzers on Hill 8815, as well as the batteries at Khe Sanh. In addition, Marine jets armed with 500-pound bombs streaked in and literally blew the top off of the easternmost enemy hill, while other fighter/bombers completely smothered one NVA counterattack with napalm.

A CH-46 helicopter from Mari, Aircraft Group 36 was shot down while attempting to evacuate casualties but another Sea Knight swooped in and picked up the pilot and copilot. The crew chief had jumped from the blazing chopper while it was still airborne and broke his leg; he was rescued by Lieutenant Fromme's men, This, however, was the only highlight for the North Vietnamese because Company I had cracked, the center of their defense and, under the savage air and artillery bombardment, the rest of the line was beginning to crumble.(46)

Lieutenant Colonel Alderman realized that his men were gaining the advantage and requested reinforcements with which to exploit the situation. Colonel Lownds, however, denied the request and directed the 3/26 commander to pull Company I back to Hill 881S immediately.

The order was passed on to Captain Dabney and it hit him like a thunderbolt. His men had been fighting hard all day and he hated to tell them to call it off at that point. Nonetheless, he rapidly disengaged, collected his casualties, and withdrew. The struggle had cost the enemy dearly: 103 North Vietnamese were killed while friendly losses were 7 killed, including two platoon commanders, and 35 wounded. As the weary Marines trudged back to Hill 881S, they were understandably disappointed at not being able to continue the attack. It wasn't until later that they learned why they had been halted just when victory was in sight.(*)(47)

(*) NVA casualties were obviously much greater than 103 dead because the Marines counted only those bodies found during the withdrawal.

Colonel Lownds' decision to break off the battle was not born out of faintheartedness, but was based on a valuable piece of intelligence that he received earlier in the afternoon. That intelligence came in the form of a NVA first lieutenant who was the commanding officer of the 14th Antiaircraft Compaq, 95C Regiment, 325C NVA Division; at 1400, he appeared off the eastern end of the runway with an AK-47 rifle in one hand and a white flag in the other. Under the covering guns of two Ontos, a fire team from the 2d Platoon, Company B, 1/26, took the young man in tow and, after Lieutenant Colonel Wilkinson had questioned him briefly, the lieutenant was hustled off to the regimental intelligence section for interrogation. The lieutenant had no compunction about talking and gave the Marines a detailed description of the forthcoming Communist offensive.

As it turned out, the accuracy of the account was surpassed only by its timeliness, because the first series of attacks was scheduled for that very night--against Hills 861 and 881S. At the time Colonel Lownds received this news, Company I was heavily engaged 1,000 meters north of its defensive perimeter and he definitely did not want Captain Dabney and his men to be caught away from their fortified outpost when the NVA struck. Consequently, Lieutenant Colonel Alderman's request for reinforcements to press his advantage was denied. (48)

When the first enemy rounds began falling on Hill 861 shortly after midnight, Marines all along the front were in bunkers and trenches--waiting. The heavy mortar barrage lasted about 30 minutes and was supplemented by RPG, small arms, and automatic weapons fire. This was followed by approximately 300 NVA troops who assaulted Hill 861. Tie van of the attacking force was made up of sapper teams that rushed forward with bangalore torpedoes and satchel charges to breach the defensive wire. Assault troops then poured through the gaps but were met and, in most sectors, stopped cold by interlocking bands of grazing machine gun fire.

In spite of the defensive fire, enemy soldiers penetrated the K/3/26 lines on the southwestern side of the hill and overran the helo landing zone. The Company K perimeter encompassed a saddle, thus the crest of 861 was actually two hills; the landing zone was on the lower one and the company CP was perched atop a steep rise to the northeast. Before the enemy could exploit the penetration, the Marines counterattacked down the trenchline and pinched off the salient.

After vicious hand-to-hand fighting, the men of Company K isolated the pocket and wipe out the North Vietnamese. Had the enemy been able to flood the breach with his reserves, the situation might have become extremely critical. When the fighting subsided, 47 NVA bodies were strewn over the hilltop while four Marines died holding their ground.(*)

(*) Many more North Vietnamese died that night than were found The stench from the bodies decaying in the jungle around the hill became so strong that the men of K/3/26 were forced to wear their gas masks for several days.

During the attack on 861, the 3d Battalion command group remained on Hill 881S because bad weather prevented Lieutenant Colonel Alderman and his operations officer from returning to the combat base.(**)(50)

(**) Throughout the night, Lieutenant Colonel Alderman supervised defensive operations from 881S and was assisted by an alternate battalion command group at the base which was headed by the 3/26 Executive Officer, Major Joseph M. Loughran, Jr.

Major Caulfield contacted the Company command post by radio and found out that the fighting was indeed heavy. The company commander, Captain Norman J. Jasper, Jr., had been hit three times and was out of action; the executive officer, First Lieutenant Jerry N. Saulsbury, was running the show. The company gunnery sergeant was dead, the first sergeant was badly wounded, and the radio operator had been blinded by powder burns. Major Caulfield later recalled that the young Marine remained at his post for almost two hours before being relieved and was "as calm, cool, and collected as a telephone operator in New York City," even though he could not see a thing. (51)

Some men on the hill had a rather unusual way of keeping their spirits up during the fight as First Sergeant Stephen L. Goddard discovered. The first sergeant had been hit in the neck and was pinching an artery shut with his fingers to keep from bleeding to death. As he moved around the perimeter, the Top heard a sound that simply had no place on a battlefield--somebody was singing.

After tracing the sound to a mortar pit, Goddard peered into the emplacement and found the gunners bellowing out one stanza after another as they dropped rounas into the tubes. The "ammo humpers" were also singing as they broke open boxes of ammunition and passed the rounds to the gunners. Naturally, the name of the song was "The Marines Hymn."(52)

Enemy Failure

One decisive factor in this battle was that Hill 881S was not attacked. Company I did not receive a single mortar round and the reprieve left the Marines free to lend unhindered support to their comrades on 861. The bulk of this fire came from the Company I 81mm mortar section. Since Lieutenant Colonel Alderman and Major Caulfield were concerned about the possibility of their position being attacked, they were careful not to deplete their ammunition. Major Caulfield personally authorized the expenditure of every 20-round lot so he knew exactly how many mortar rounds went out that night--680. The mortar tubes became so hot that the Marines had to use their precious drinking water to keep them cool enough to fire; after the water, the men used fruit juice. When the juice ran out, they urinated on the tubes. The spirited support of Company I and its attached elements played a big part in blunting the attack.(53)

Here are two plausible explanations for the enemy's failure to coordinate the attack on Hill 861 with one on 881S. Lieutenant Colonel Alderman and Major Caulfield felt that Captain Dabney's fight on the afternoon of 20 January had crippled the NVA battalion which was slated for the attack on Hill 881S and disrupted the enemy's entire schedule. On the other hand, Company I had emerged from the engagement with relatively light casualties and was in fighting trim on the morning of the 21st.

Another possibility was the manner in which Colonel Lownds utilized artillery and aircraft. The regimental commander did not use his supporting arms to break up the attack directly; he left that job up to the defenders themselves. Instead, the colonel called in massive air and artillery concentrations on points where the enemy would more than likely marshal his reserves. Much of the credit belong to Lieutenant Colonel Hennelly's batteries at the base. One infantry officer on Hill 881S, who observed the fire, described the Marine artillery as "absolutely and positively superb."

Throughout the battle, the North Vietnamese assault commander was heard frantically screaming for his reserves--he never received an answer. The fact that the initial attack on 861 was not followed up by another effort lent credence to the theory that the backup force was being cut to pieces to the rear while the assault troops were dying on the wire.(54)

The Marines did not have long to gloat over their victory because at 0530 on the 21st the KSCB was subjected to an intense barrage. Hundreds of 82mm mortar rounds, artillery shells, and 122mm rockets slammed into the compound as Marines dived into bunkers and trenches.(*)(55)

(*) On Hill 881S, Captain Dabney watched several hundred 122mm rockets lift off from the southern slope of 881N--a scant 300 meters beyond the farthest point of his advance the day before. The enemy defensive positions between the two hills were obviously designed to protect these launching sites. At the combat base, the barrage did not catch the Marines completely by surprise; the regimental intelligence section had warned that an enemy attack was imminent and the entire base was on Red Alert.

Damage at "ground zero" was extensive: several helicopters were destroyed, trucks and tents were riddled, one messhall was flattened, and fuel storage areas were set ablaze. Colonel Lownds' quarters were demolished but, fortunately, the regimental commander was not in his hut at the time. One of the first incoming rounds found its mark scoring a direct hit on the largest ammunition dump, which was situated near the eastern end of the runway. The dump erupted in a series of blinding explosions which rocked the base and belched thousand of burning artillery and mortar rounds into the air.

Many of these maverick projectiles exploded on impact and added to the devastation. Thousands of rounds were destroyed and much of this ammunition "cooked off" in the flames for the next 48 hours. In addition, one enemy round hit a cache of tear gas (CS) releasing clouds of the pungent vapor which saturated the entire base.(56)

The main ammunition dump was just inside the perimeter manned by Company B, 1/26, and the 2d Platoon, commanded by Second Lieutenant John W. Dillon, was in the hotseat throughout the attack. The unit occupied a trenchline which, at places, passed as close as 30 meters to the dump. In spite of the proximity of the "blast furnace," Lieutenant Dillon's men stayed in their positions, answered with their own mortars, and braced for the ground attack which never came. Throughout the ordeal, the 2d Platoon lines became an impact area for all sizes of duds from the dump which literally filled the trenchline with unexploded ordnance. In addition, the men were pelted by tiny slivers of steel from the exploding antipersonnel ammunition which became embedded in their flak jackets, clothing, and bare flesh.(57)

The fire raging in the main dump also hampered the rest of the 1st Battalion. The 81mm mortar platoon fired hundreds of rounds in retaliation but the ammo carriers had to crawl to and from the pits because of the exploding ammunition. Captain Kenneth W. Pipes, commanding officer of Company B, had to displace his command post three times when each position became untenable. Neither was the battalion CP exempt; at about 1000, a large quantity of C-4 plastic explosives in the blazing dump was touched off and the resulting shock waves cracked the timbers holding up the roof of Lieutenant Colonel Wilkinson's command bunker.

As the roof settled, several members of the staff were knocked to the floor. For a moment it appeared that the entire overhead would collapse but after sinking about a foot, the cracked timbers held. With a sigh of relief, the men inside quickly shored up the roof and went about their duties.(58)

The sudden onslaught produced a number of heroes, most of whom went unnoticed. Members of Force Logistics Group Bravo, and other personnel permanently stationed at the ammunition dump, charged into the inferno with fire extinguishers and shovels to fight the blaze. Motor transport drivers darted from the safety of their bunkers to move trucks and other vehicles into revetments. Artillerymen quickly manned their guns and began returning fire. The executive officer of 1/13, Major Ronald W. Campbell, ignored the heavy barrage and raced from one shell hole to another analyzing the craters and collecting fragments so that he could determine the caliber of the enemy weapons as well as the direction from which they were being fired. Much of the counterbattery fire was a direct result of his efforts.(59)

Three other artillerymen from Battery C, 1/13, performed an equally heroic feat in the midst of the intense shelling. When the dump exploded, the C/1/13 positions, like those of 1/26, were showered with hundreds of hot duds which presented a grave danger to the battery.

The battery commander, Captain William J. O'Connor, the executive officer, First Lieutenant William L. Everhart, and the supply sergeant, Sergeant Ronnie D. Whiteknight immediately began picking up the burning rounds and carrying them to a hole approximately 50 meters behind the gun pits. For three hours, these Marines carried out between 75 and 100 duds and disposed of them, knowing that any second one might explode. When the searing clouds of tear gas swept over the battery, many gunners were cut off from their gas masks. Lieutenant Everhart and Sergeant Whiteknight quickly gathered up as many masks as they could carry and distributed them to the men in the gun positions. The "cannon cockers" donned the masks and kept their howitzers in action throughout the attack.(60)

By this time, most of 1/13 had ceased firing counterbattery missions and was supporting the defense force at Khe Sanh Village. An hour after the KSCB came under attack, the Combined Action Company (CACO) and a South Vietnamese Regional Forces (RF) company stationed in the village were hit by elements of the 304th NVA_ Division. The enemy troops breached the defensive wire, penetrated the compound, and seized the dispensary. Heavy street fighting ensued and, at 0810, the defenders finally drove the enemy force from the village.

Later that afternoon, two NVA companies again assaulted the village but, this time, artillery and strike aircraft broke up the attack. Upon request of the defenders, Lieutenant Colonel Hennelly's battalion fired over 1,030 artillery rounds with variable time fuzes which resulted in airbursts over the defensive wire. During the action, a single Marine A-6A "Intruder" knifed through the ground fire and killed about 100 of the attackers. Those enemy soldiers who persisted were taken care of by close-in defensive fires and, when the fighting subsided, an American advisor counted 123 North Vietnamese bodies on or around the barbed wire.(61)

Withdrawal

Following the second attack, Colonel Lownds decided to withdraw these isolated units to the confines of the KSCB. The village, which was the seat of the Huong Hoa District headquarters was not an ideal defensive position. The Allies were hampered by restricted fields of fire and there was a temple just outside the village which overlooked the perimeter.

Most important, a regiment of the 304th NVA Division was operating in the immediate, vicinity. The colonel decided that he would rather evacuate the village while he could, instead of waiting until its occupants were surrounded and fighting for their lives. Helicopters flew in and picked up the Marines and U. S. Army advisors; the Vietnamese troops and officials of the local government moved overland

Upon arrival, the CACO and RF companies, which totaled about 250 men, took up positions in the southwestern sector of the base and were absorbed by FOB-3. (*) (62)

(*) The Huong Hoa District Headquarters operated from within the KSCB throughout the siege.

There was one other encounter on the 21st. At 1950, the 2d Platoon, L/3/26, reported 25-30 enemy soldiers crawling toward the wire bordering Red Sector. The Marines opened fire and, within an hour, killed 14 North Vietnamese. Remnants of the attacking force were seen dragging dead and wounded comrades from the battlefield. Cumulative friendly casualties for the day, including those incurred on Hill 861, were 9 killed, 37 wounded and evacuated (Medevaced), plus 38 wounded but returned to duty.(63)

When the events of the 21st were flashed to the world via the news media, many self-appointed experts in the United States began to speak out concerning the feasibility of maintaining the garrison at Khe Sanh. Those who opposed the planned defense felt that the Marines had been able to remain there only at the pleasure of the NVA. They pointed out that, in the preceding months, the installation had been of little concern to the North Vietnamese because it was ineffective as a deterrent to infiltration.

The undermanned 26th Marines could not occupy the perimeter, man the hill outposts, and simultaneously conduct the constant, large-unit sweeps necessary to control the area. Therefore, the enemy could simply skirt the base and ignore it. A build-up, however, would make the prize worthwhile for the NVA, which badly needed a crushing victory over the Americans for propaganda purposes. By concentrating forces at Khe Sanh, the theory went, the Allies would be playing into the enemy's hands because the base was isolated and, with Route 9 interdicted, had to be completely supplied by air. Fearing that Khe Sanh would become an American Dien Bien Phu, the critics favored a pull-out.

Holding Khe Sanh

Holding Khe Sanh

In Vietnam, where the decision was being made, there was little disagreement. The two key figures, General Westmoreland and General Cushman, "after discussing all aspects of the situation, were in complete agreement from the start."(64) There were several reasons they decided to hold Khe Sanh at that time. The base and adjacent outposts commanded the Khe Sanh Plateau and the main avenue of approach into eastern Qsang Tri Province.

Left: Gen. Westmoreland. Right: Gen. Cushman.

While the installation was not 100 percent effective as a deterrent to infiltration, it was a solid block to enemy invasion and motorized supply from the west. Had the Allies possessed greater strength in the northern provinces, they might have achieved the same ends with large and frequent airmobile assaults--a concept which General Cushman had advocated for some time.

In January 1968, he had neither the helicopter resources, the troops, nor the logistical bases for such operations. The weather was another critical factor because the poor visibility and low overcasts attendant to the monsoon season made helicopter operations hazardous to say the least. Even if the III MAF commander had the materiel and manpower for such large airmobile assaults, the weather precluded any such effort before March or April. Until that time, the job of sealing off Route 9 would have to be left up to the 26th Marines.(65)

An additional consideration for holding the base was the rare and valuable opportunity to engage and destroy an heretofore elusive foe. Up to this time, there was hardly a commander in Vietnam who, at one time or another, had not been frustrated in his attempts to box in the slippery NVA and VC units. At Khe Sanh, the enemy showed no desire to hit and run but rather to stand and fight; it was a good idea to oblige him. In effect, the 26th Marines would fix the enemy in position around the base while Allied air and artillery battered him into senselessness.

Furthermore, the defense was envisioned as a classic example of economy of force. Although there was conjecture that the NVA was trying to draw American units to the DMZ area, the fact remained that two crack NVA divisions, which otherwise might have participated in the later attacks on Hue and Quang Tri City, were tied down far from the vital internal organs of South Vietnam by one reinforced Marine regiment.(66)

Thus, with only two choices available--withdraw or reinforce --ComUSMACV chose the latter. In his "Report On The War In Vietnam," General Westmoreland stated:

- The question was whether we could afford the troops to reinforce, keep them supplied by air, and defeat an enemy far superior in numbers as we waited for the weather to clear, build forward bases, and made preparations for an overland relief expedition. I believed we could do all of those things. With the concurrence of the III Marine Amphibious Force Commander, Lieutenant General Robert E. Cushman, Jr., I made the decision to reinforce and hold the area while destroying the enemy with our massive firepower and to prepare for offensive operations when the weather became favorable.

General Westmoreland reported his decision to Washington and more troops began to pour into the combat base.(67)

On 22 January, the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John F. Mitchell, was transferred to the operational control of the 26th Marines and arrived at 1900 the same day. Ever since the three high ranking NVA officers were killed outside Red Sector, General Tompkins and Colonel Lownds were concerned over the unhealthy interest that the North Vietnamese were showing in the western perimeter.

When 1/9 arrived, the colonel directed the battalion commander to establish defensive positions at the rock quarry, 1,500 meters southwest of the strip. Lieutenant Colonel Mitchell moved his unit overland and set up a kidney-shaped perimeter around the quarry with his CP perched atop a hill. In addition, he dispatched a platoon from Company A approximately 500 meters further west to set up a combat outpost on a small knob. The 1/9 lines curved near, but did not tie in with, those of L/3/26; the small gap, however, could easily be covered by fire. The western approach was firmly blocked.(68) (See Map 6).

General Tompkins and Colonel Lownds also discussed plans for the opposite side of the compound. This approach would have been the most difficult for the North Vietnamese to negotiate because the terrain east of the runway dropped off sharply to the river below. This steep grade, however, was heavily wooded and provided the enemy with excellent concealment. The WA troops, masters at the art of camouflage, could have maneuvered dangerously close to the Marine lines before being detected.

General Tompkins and Colonel Lownds also discussed plans for the opposite side of the compound. This approach would have been the most difficult for the North Vietnamese to negotiate because the terrain east of the runway dropped off sharply to the river below. This steep grade, however, was heavily wooded and provided the enemy with excellent concealment. The WA troops, masters at the art of camouflage, could have maneuvered dangerously close to the Marine lines before being detected.

Location of outposts.

The main reason for concern, however, was the testimony of the cooperative NVA lieutenant who had surrendered on the 20th. According to the lieutenant, the eastern avenue of approach was the key with which the Communists hoped to unlock the Khe Sanh defenses. First, the NVA intended to attack and seize Hills 861 and 881S, both of which would serve as fire support bases. From these commanding positions, the enemy would push into the valley and apply pressure along the northern and western portion of the Marines' perimeter. These efforts, however, were simply a diversion to conceal the main thrust--a regimental ground attack from the opposite quarter. An assault regiment from the 304th Division would skirt the base to the south, hook around to the east, and attack paralleling the runway through the 1/26 lines.

Once the compound was penetrated, the North Vietnamese anticipated that the entire Marine defense system would collapse.(69)

On 27 January, the 37th ARVN Ranger Battalion, the fifth and final battalion allotted for Khe Sanh, arrived.(*)(70)

(*) ARVN battalions were considerably smaller than Marine battalions and the 37th Ranger was no exception. Even by Vietnamese standards, the unit was undermanned; it had 318 men when it arrived.

Understandably, Colonel Lownds moved the ARVN unit into the eastern portion of the perimeter to reinforce the 1st Battalion. Actually, the Marines were backing-up the South Vietnamese because the Ranger Battalion occupied trenches some 200 meters outside the 1/26 lines. Lieutenant Colonel Wilkinson's men had already prepared these defensive positions for the new arrivals.

The new trenchline extended from the northeast corner of Blue Sector, looped across the runway, paralleled the inner trenchline of 1/26, and tied back in with the Marine lines on the southeastern corner of Grey Sector. (See Map 7) The only gap was where the runway extended through the ARVN lines; this section was covered by two Ontos. At night, the gap was sealed off with strands of German Tape--a new type of razor-sharp barbed wire which was extremely difficult to breach. The North Vietnamese would now have to penetrate two lines of defense if they approached from the east.(71)

As January drew to a close, the situation at Khe Sanh could be summed up in three words--enemy attack imminent. As a result of rumblings of a large-scale Communist offensive throughout South Vietnam, the scheduled Vietnamese Lunar New Year (TET) ceasefire was cancelled in I Corps and the 26th Marines braced for the inevitable.

While they waited, they filled sandbags, dug deeper trenches, reinforced bunkers, conducted local security patrols, and, in general, established a pattern which would remain unbroken for the next two months. The NVA also established a routine as enemy gunners daily shelled the base and hill outposts while assault units probed for a soft spot. Thus the two adversaries faced each other like boxers in a championship bout; one danced around nimbly throwing jabs while the second stood fast waiting to score the counterpunch that would end the fight.(72)

Back to Table of Contents -- US Marines: Khe Sanh

Back to Vietnam Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com