With the departure of the 3d Marines, a relative calm prevailed at Khe Sanh for the remainder of the year. Although occasional encounters and sightings indicated that the Communists still had an interest in the area, there was a marked decrease in large unit contacts and the tempo of operations slackened to a preinvasion pace. Such was not the case in other portions of Quang Tri Province.

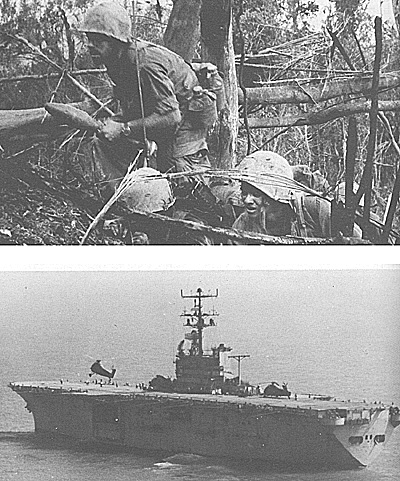

Top: Marines attack near DMZ duringOperation Prairie.

Bottom: USS Iwo Jima carried Marine Battalion Landing Teams to augment III MAF forces.

During the summer and fall of 1967, the center of activity shifted to the eastern DMZ area. After being battered and thrown for a loss on their end sweep, the Communists concentrated on the middle of the line again. With an estimated 37 battalions poised along the border, the NVA constituted a genuine threat to the northernmost province. At times as many as eight Marine battalions were shuttled into the area for short-term operations and three or four were there full time, but the enemy's intensified campaign created a demand for more troops. As a result, General Westmoreland was forced to make major force realignments throughout South Vietnam to satisfy the troop requirements in I Corps.(14)

General Westmoreland drew the bulk of these reinforcements from areas in Vietnam which, at the time, were under less pressure than the five northern provinces. During April and May 1967, Task Force OREGON, comprised of nine U. S. Army battalions from II and III Corps, moved into the Chu Lai-Duc Pho region and was placed under the operational control of General Walt.

By the end of May, five battalions of the 5th and 7th Marines at Chu Lai had been released for service further north. Two of these units moved into the Nui Loc Son Basin northwest of Tam Ky to conduct offensive operations and support the sagging Vietnamese Revolutionary Development efforts. The other three settled in the Da Nang tactical area of responsibility (TAOR) and in turn released two Marine battalions, 1/1 and 2/1, which moved to Thua Thien and Quang Tri provinces.

In addition to his in-country assets, General Westmoreland also called on Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp, Commander in Chief, Pacific, for reinforcements. Besides the two Special Landing Forces afloat with the U. S. Seventh Fleet, the Pacific Command maintained a Marine Battalion Landing Team (BLT 3/4) as an amphibious reserve on Okinawa.(*)(15)

(*) The two Special Landing Forces of the Seventh Fleet are each comprised of a Marine Battalion Landing Team and a Marine helicopter squadron, and provide ComUSMACV/CG, III MAF with a highly-flexible, amphibious striking force for operations along the South Vietnam littoral. During the amphibious operation, operational control of the SLF remains with the Amphibious Task Force Commander designated by Commander, Seventh Fleet. This relationship may persist throughout the operation if coordination with forces ashore does not dictate otherwise. When the Special Landing Force is firmly established ashore, operational control may be passed to CG, III MAF who, in turn, may shift this control to the division in whose area the SLF is operating. Under such circumstances, operational control of the helicopter squadron is passed by CG III MAF to the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing.)

Actually, this unit was part of the BLT rotation system whereby battalions were periodically shuttled out of Vietnam for retraining and refurbishing in Okinawa before assignment to the SLF.

ComUSMACV needed the unit and got it. On 15 May, 3/4 began an airlift from Okinawa to Dong Ha by Air Force and Marine C-130 aircraft and within 31 hours the 1,233-man force was in-country. After the realignment of units in I Corps was complete, there was a net increase of four USMC battalions in the DMZ area making a total of seven. Additionally, the SLFs, cruising off the Vietnamese coast, provided two more battalions which could be landed quickly and added to the III MAF inventory. SLF `Alpha (BLT 1/3 and HMM-362) was placed on 24-hour alert to come ashore and SLF Bravo (BLT 2/3 and HMM-164) was given a 96-hour reaction time.(16)

During the second half of 1967, the enemy offensive south of the DMZ was a bloody repetition of the previous year's effort. With more courage than good sense, the NVA streamed across the DMZ throughout the summer only to be met and systematically chewed up in one engagement after another. In July, the enemy, supported by his long-range artillery along the Ben Hai, mounted a major thrust against the 9th Marines near the strongpoint of Con Thien. Reinforced by SLFs Alpha and Bravo, the 9th Marines countered with Operation BUFFALO and, between the 2d and 14th of July, killed 1,290 NVA. Marine losses were 159 dead and 345 wounded.(17)

Fire Attacks

After this crushing defeat, the NVA shifted its emphasis from direct infantry assaults to attacks by fire. Utilizing long-range rockets and artillery pieces tucked away in caves and treelines along the DMZ, the enemy regularly shelled Marine fire support and logistical bases from Cam Lo to Cua Viet.

One of the most destructive attacks was against Dong Ha where, on 3 September, 41 enemy artillery rounds hit the base and touched off a series of spectacular explosions which lasted for over four hours. Several helicopters were damaged but, more important, a fuel farm and a huge stockpile of ammunition went up in smoke. Thousands of gallons of fuel and tons of ammunition were destroyed. The enormous column of smoke from the exploding dumps rose above 12,000 feet and was visible as far south as Hue-Phu Bai.(18)

The preponderance of enemy fire, however, was directed against Con Thien. That small strongpoint, never garrisoned by more than a reinforced battalion, was situated atop Hill 158, 10 miles northwest of Dong Ha and, from their small perch, the Marines had a commanding view of any activity in the area. In addition, from one to three battalions were always in the immediate vicinity and deployed so that they could outflank any major enemy force which tried to attack the strongpoint.

Con Thien also anchored the western end of "the barrier," a 600-meterwide trace which extended eastward some eight miles to Gio Linh. This strip was part of an anti-infiltration system and had been bulldozed flat to aid in visual detection.(*)(19)

(*) The system was an anti-infiltration barrier just south of the DMZ. Obstacles were used to channelize the enemy. Strongpoints, such as Con Thien, served as patrol bases and fire support bases.

Because of its strategic importance, Con Thien became the scene of heavy fighting. The base itself was subjected to several ground attacks, plus an almost incessant artillery bombardment which, at its peak, reached 1,233 rounds in one 24hour period. Most of the NVA and Marine casualties, however, were sustained by maneuver elements in the surrounding area. Operation KINGFISHER, which succeeded BUFFALO, continued around Con Thien and by 31 October, when it was superseded by two new operations, had accounted for 1,117 enemy dead. Marine losses were 340 killed.(**)(20)

(**) In addition to the action near the DMZ, there was one other area in I Corps that was a hub of activity. The Nui Loc Son Basin, a rice rich coastal plain between Hoi An and Tam Ky, was the operating area of the 2d NVA Division. Between April and October 1967, Marine, U. S. Army, and ARVN troops conducted 13 major operations (including 3 SLF landings) in this region and killed 5,395 enemy soldiers. By the end of the year, the 2d NVA Division was temporarily rendered useless as a fighting unit.

While heavy fighting raged elsewhere, action around Khe Sanh continued to be light and sporadic. Immediately after its arrival on 13 May, Colonel Padley's undermanned 26th Marines commenced Operation CROCKETT.(*)(21)

(*) The official designation of the unit at Khe Sanh was Regimental Landing Team 26 (Forward) which consisted of one battalion and a lightly staffed headquarters. The other two battalions were in-country but under the operational control of other units. The rest of the headquarters, RLT-26 (Rear), remained at Camp Schwab, Okinawa as a pipeline for replacements. RLT-26 (Forward) was under the operational control of the 3d MarDiv and the administrative control of the 9th MAB. Any further mention of the 26th Marines will refer only to RLT-26 (Forward).

Terrain Mission

The mission was to occupy key terrain, deny the enemy access into vital areas, conduct reconnaissance-in-force operations to destroy any elements within the TAOR, and provide security for the base and adjacent outposts. Colonel Padley was to support the Vietnamese irregular forces with his organic artillery as well as coordinate the efforts of the American advisors to those units. He also had the responsibility of maintaining small reconnaissance teams for long-range surveillance.(22)

To accomplish his mission, the colonel had one infantry battalion, 1/26, a skeleton headquarters, and an artillery group under the control of 1/13. The 1st Battalion, 26th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James B. Wilkinson, maintained one rifle company on Hill 881S and one on 861; a security detachment on Hill 950 to protect a communication relay site; a rifle company and the Headquarters and Service Company (H&S Co) for base security; and one company in reserve. The units on the hill outposts patrolled continuously within a 4,000-meter radius of their positions.

Reconnaissance teams were inserted further out, primarily to the north and northwest. Whenever evidence revealed enemy activity in an area, company-sized search and destroy sweeps were conducted. Although intelligence reports indicated that the three regiments of the 325C NVA Division (i.e. 95C, 101D, and 29th) were still in therKhe Sanh TAOR, there were few contacts during the opening weeks of the operation.(23)

Toward the end of May and throughout June, however, activity picked up. On 21 May, elements of Company A, 1/26, clashed sharply with a reinforced enemy company; 25 NVA and 2 Marines were killed. The same day, the Lang Vei CIDG camp was attacked by an enemy platoon. On 6 June, the radio relay site on Hill 950 was hit by an NVA force of unknown size and the combat base was mortared. The following morning a patrol from Company B, 1/26, engaged another enemy company approximately 2,000 meters northwest of Hill 881S.

A platoon from Company A was helilifted to the scene and the two Marine units killed 66 NVA while losing 18 men. Due to the increasing number of contacts, the 3d Battalion, 26th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Kurt L. Hoch, was transferred to the operational control of its parent unit and arrived at Khe Sanh on 13 June. Two weeks later, the newly arrived unit got a crack at the NVA when Companies I and L engaged two enemy companies 5,000 meters southwest of the base and, along with air and artillery, killed 35.(24)

Operation CROCKETT continued as a two-battalion effort until 16 July when it terminated. The cumulative casualty figures were 204 enemy KIA (confirmed), 52 Marines KIA, and 255 Marines wounded. The following day, operations continued under a new name--ARDMORE. The name was changed; the mission, the units, and the TAOR remained basically the same. But again the fighting tapered off. Except for occasional contacts by reconnaissance teams and patrols, July and August were quiet.(25)

On 12 August, Colonel David E. Lownds relieved Colonel Padley as the commanding officer of the 26th Marines. At this time the 3d Marine Division was deployed from the area north of Da Nang to the DMZ and from the South China Sea to the Laotian border. In order to maintain the initiative, Lieutenant General Robert E. Cushman, Jr., who had relieved General Walt as CG, III MAF in June, drew down on certain units to provide sufficient infantry strength for other operations.

Except for several small engagements Khe Sanh had remained relatively quiet; therefore, on the day after Colonel Lownds assumed command, the regiment was whittled down by two companies when K and L, 3/26, were transferred to the 9th Marines for Operation KINGFISHER. Three weeks later, the rest of 3/26 was also withdrawn and, as far as Marine units were concerned, Colonel Lownds found himself "not so much a regimental commander as the supervisor of a battalion commander."

The colonel, however, was still responsible for coordinating the efforts of all the other Allied units (CACO, CIDG, RF, etc) in the Khe Sanh TAOR.(26)

As Operation ARDMORE dragged on, the Marines at Khe Sanh concentrated on improving the combat base. The men were kept busy constructing bunkers and trenches both inside the perimeter and on the hill outposts. On the hills, this proved to be no small task as was pointed out by the 1/26 battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Wilkinson:

- The monsoon rains had little effect on 881, but when the first torrential rains of the season hit 861 the results were disastrous. The trenchline which encircled the hill washed away completely on one side of the position and caved in on another side. Some bunkers collapsed while others were so weakened they had to be completely rebuilt.

Because of the poor soil and the steepness of the terrain, the new bunkers were built almost completely above ground. To provide drainage, twenty-seven 55 gallon steel drums, with the tops and bottoms removed, were installed in the sides of the trenches around 861 so water would not stand in the trenches-. (Culvert material was not available.) All bunker materials, as well as other supplies, were delivered to the hills by helicopter.

Attempts were made to obtain logs for fighting positions and bunkers in the canopied jungle flanking the hills. This idea was not successful. The trees close to 881 and 861 were so filled with shrapnel from the battles the previous spring that the engineers did not want to ruin their chain saws on the metal .... In spite of the shortages, Marines of 1/26 worked extremely hard until every Marine on 881(S) and 861 had overhead cover.(27)

Another bit of foresight which was to prove a God-send in the succeeding months was the decision by higher headquarters to improve the airstrip. The original runway had been a dirt strip on top of which the U. S. Navy Seabees had laid aluminum matting. The 3,900-foot strip, however, did not have a rock base and as a result of the heavy monsoon rains, mud formed under the matting causing it to buckle in several places.

Upon direction, Colonel Lownds closed the field on 17 August. His men located a hill 1,500 meters southwest of the perimeter which served as a quarry. Three 15-ton rock crushers, along with other heavy equipment, were hauled in and the Marine and Seabee working parties started the repairs. During September and October, U. S. Air Force C-130s of the 315th Air Division (under the operational control of the 834th Air Division) delivered 2,350 tons of matting, asphalt, and other construction material to the base by paradrops and a special low-altitude extraction system. (See page 76) While the field was shut down, resupply missions were handled by helicopters and C-7 "Caribou" which could land on short segments of the strip. Work continued until 27 October when the field was reopened to C-123 aircraft and later, to C-130s.(28)

Operation Scotland

On 31 October, Operation ARDMORE came to an uneventful conclusion. The absence of any major engagements was mirrored in the casualty figures which showed that in three and a half months, 113 NVA and 10 Marines were killed. The next day, 1 November, the 26th Marines commenced another operation, new in name only--SCOTLAND I. Again the mission and units remained the same, and while the area of operations was altered slightly, SCOTLAND I was basically just an extension of ARDMORE.(29)

One incident in November which was to have a tremendous effect on the future of the combat base was the arrival of Major General Rathvon McC. Tompkins at Phu Bai as the new Commanding General, 3d Marine Division. General Tompkins took over from Brigadier General Louis Metzger who had been serving as the Acting Division Commander following the death of Major General Bruno Hochmuth in a helicopter crash on 14 November.

In addition to being an extremely able commander, General TompkinE possessed a peppery yet gentlemanly quality which, in the gloom that later shrouded Khe Sanh, often lifted the spirits of his subordinates. His numerous inspection trips, even to the most isolated units, provided the division commander with a firsthand knowledge of the tactical situation in northern I Corps which would never have been gained by simply sitting behind a desk. When the heavy fighting broke out at Khe Sanh, the general visited the combat base almost daily. Few people were to influence the coming battle more than General Tompkins or have as many close calls.(30)

During December, there was another surge of enemy activity. Reconnaissance teams reported large groups of NVA moving into the area and, this time, they were not passing through; they were staying. There was an increased number of contacts between Marine patrols and enemy units. The companies on Hills 881S and 861 began receiving more and more sniper fire. Not only the hill outposts, but the combat base itself, received numerous probes along the perimeter.

In some cases, the defensive wire was cut and replaced in such a manner that the break was hard to detect. The situation warranted action, and again General Cushman directed 3/26 to rejoin the regiment. On 13 December, the 3d Battalion, under its new commander, Lieutenant Colonel Harry L. Alderman (who assumed command 21 August), was airlifted back to Khe Sanh and the 26th Marines.(31)

On the 21st, the newly-arrived Marines saddled up and took to the field. This was the first time that Colonel Lownds had been able to commit a battalion-sized force since 3/26 had left Khe Ssnh in August. Lieutenant Colonel Alderman's unit was helilifted to 881S where it conducted a sweep toward Hill 918, some 5,100 meters to the west, and then returned to the combat base by the way of Hill 689. The 3d Battalion made no contact with the enemy during the five-day operation but the effort proved to be extremely valuable.

First of all, the men of 3/26 became familiar with the terrain to the west and south of Hill 881S--a position which was later occupied by elements of the 3d Battalion. The Marines located the best avenues of approach to the hill, as well as probable sites for the enemy's supporting weapons.

Secondly, and most important, the unit turned up evidence (fresh foxholes, well-used trails, caches, etc.) which indicated that the NVA was moving into the area in force. These signs further strengthened the battalion and regimental commanders' belief that "things were picking up," and the confrontation which many predicted would come was not far off. Captain Richard D. Camp, the company commander of L/3/26 put it a little more bluntly: "I can smell.../the enemy/."(32)

Back to Table of Contents -- US Marines: Khe Sanh

Back to Vietnam Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com