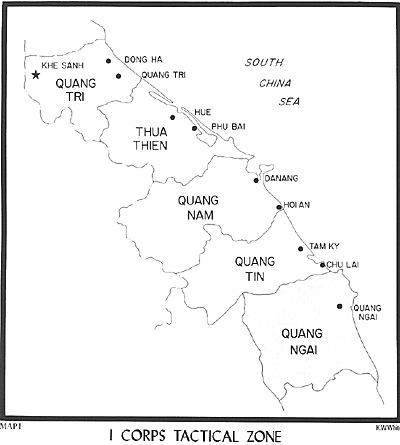

When the lead elements of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Frederick J. Karch, slogged ashore at Da Nang on 8 March 1965, Communist political and military aspirations in South Vietnam received a severe jolt. The buildup of organized American combat units had begun. In May 1965, the 9th MEB was succeeded by the III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) which was comprised of the 3d Marine Division, the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, and, within a year, the 1st Marine Division. The Commanding General, III MAF was given responsibility for U. S. operations in I Corps Tactical Zone which incorporated the five northern provinces and, on 5 June 1965, Major General Lewis W. Walt assumed that role. (See Map 1). Major units of the U. S. Army moved into other portions of South Vietnam and the entire American effort came under the control of the Commander, U. S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (ComUSMACV), General William C. Westmoreland.(1)

When the lead elements of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Frederick J. Karch, slogged ashore at Da Nang on 8 March 1965, Communist political and military aspirations in South Vietnam received a severe jolt. The buildup of organized American combat units had begun. In May 1965, the 9th MEB was succeeded by the III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) which was comprised of the 3d Marine Division, the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, and, within a year, the 1st Marine Division. The Commanding General, III MAF was given responsibility for U. S. operations in I Corps Tactical Zone which incorporated the five northern provinces and, on 5 June 1965, Major General Lewis W. Walt assumed that role. (See Map 1). Major units of the U. S. Army moved into other portions of South Vietnam and the entire American effort came under the control of the Commander, U. S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (ComUSMACV), General William C. Westmoreland.(1)

The Marines, in conjunction with the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), set about to wrest control of the populace in I Corps from the Viet Cong and help reassert the authority of the central government. The Allies launched an aggressive campaign designed to root out the enemy's source of strength-the local guerrilla. Allied battalion- and regimental-sized units screened this effort by seeking out and engaging Viet Cong main forces and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) elements. Smaller Marine and ARVN units went after the isolated guerrilla bands which preyed on the Vietnamese peasants.

Thousands of fire team-, squad-, and platoon-sized actions took a heavy toll of the enemy and the Viet Cong were gradually pushed out of the populated areas. Whenever a village or hamlet was secured, civic action teams moved in to fill the vacuum and began the long, tedious process of erasing the effects of prolonged Communist domination. Progress was slow. Within a year, however, the area under Government security had grown to more than 1,600 square miles and encompassed nearly half a million people.

As government influence extended deeper into the countryside, the security, health, economic well-being, and educational prospects of the peasants were constantly improved. There was an ever increasing number of enemy defectors and intelligence reports from, heretofore, unsympathetic villagers. By mid-1966, Allied military operations and pacification programs were slowly but seriously eroding the enemy's elaborate infrastructure and his hold over the people.(2)

It soon became apparent to the leaders in the North that, unless they took some bold action, ten years of preparation and their master plan for conquest of South Vietnam would go down the drain. From the Communists' standpoint, the crucial matter was not the volume of casualties they sustained, but the survival of the guerrilla infrastructure in South Vietnam. In spite of their disregard for human life, the North Vietnamese did not wish to counter the American military steamroller in the populated coastal plain of I Corps.

There, the relatively open terrain favored the overwhelming power of the Marines' supporting arms. The enemy troops would have extended supply lines, their movement could be more easily detected, and they would be further away from sanctuaries in Laos and North Vietnam. In addition, when the propaganda-conscious NVA suffered a defeat, it would be witnessed by the local populace and thus shatter the myth of Communist invincibility.

If the Marines could not be smashed, and the Communists had tried several times, they had to be diverted or thinned out. The answer to the enemy's dilemma lay along the 17th Parallel. Gradually, they massed large troop concentrations within the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), in Laos, and in the southern panhandle of North Vietnam; in short, they were opening a new front. Nguyen Van Mai, a high Communist official in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, predicted: "We will entice the Americans closer to the North Vietnamese border and ... bleed them without mercy." That remained to be seen.(3)

In response to the enemy buildup along the DMZ throughout

the summer and fall of 1966, General Walt shifted Marine units further north. The 3d Marine Division Headquarters moved from Da Nang to Phu Bai, and a Division Forward Command Post (CP) continued to Dong Ha so that it could respond rapidly to developments along the DMZ. In turn the 1st Marine Division Headquarters moved from Chu Lai to Da Nang and took control of operations in central and southern I Corps. For specific, short-term operations, the division commanders frequently delegated authority to a task force headquarters.

In response to the enemy buildup along the DMZ throughout

the summer and fall of 1966, General Walt shifted Marine units further north. The 3d Marine Division Headquarters moved from Da Nang to Phu Bai, and a Division Forward Command Post (CP) continued to Dong Ha so that it could respond rapidly to developments along the DMZ. In turn the 1st Marine Division Headquarters moved from Chu Lai to Da Nang and took control of operations in central and southern I Corps. For specific, short-term operations, the division commanders frequently delegated authority to a task force headquarters.

The task force was a semi-permanent organization composed of temporarily assigned units under one commander, usually a general officer. Because of the fluid, fast-moving type of warfare peculiar to Vietnam, the individual battalion became a key element and went where it was needed the most. It might operate under a task force headquarters or a regiment other than its own parent unit. For example, it would not be uncommon for the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines to be attached to the 3d Marines while the 2d Battalion, 3d Marines was a part of another command. Commitments were met with units that were the most readily available at the time.(4)

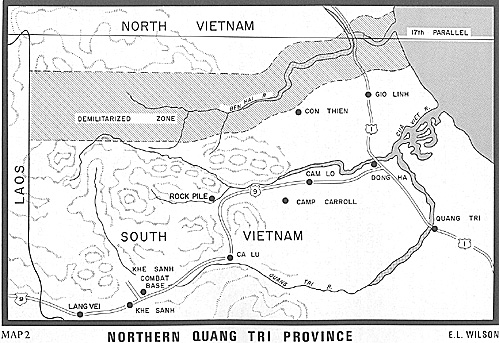

With the buildup of American troops in Quang Tri province, there logically followed the buildup of installations. Dong Ha was the largest since it served as the brain and nervous system of the entire area. Eight miles to the southwest was Camp J. J. Carroll, a large artillery base. The Marine units there were reinforced by several batteries of U. S. Army 175mm guns which had the capability of firing into North Vietnam. Located at the base of a jagged mountain ten miles west of Camp Carroll was another artillery base--the Rockpile.

This facility also had 175mm guns and extended the range of American artillery support almost to the Laotian border. In addition, the Marines built a series of strongpoints paralleling and just south of the DMZ. Gio Linh and Con Thien were the two largest sites. (See Map 2).

During the remainder of 1966 and in the first quarter of 1967, the intensity of fighting in the eastern DMZ area increased. Each time the enemy troops made a foray across the DMZ, the Marines met and defeated them. By 31 March 1967, the NVA had lost 3,492 confirmed killed in action (KIA) in the northern operations while the Marines had suffered 541 killed. For the Communists, it appeared that direct assaults across the DMZ were proving too costly--even by their standards.(5)

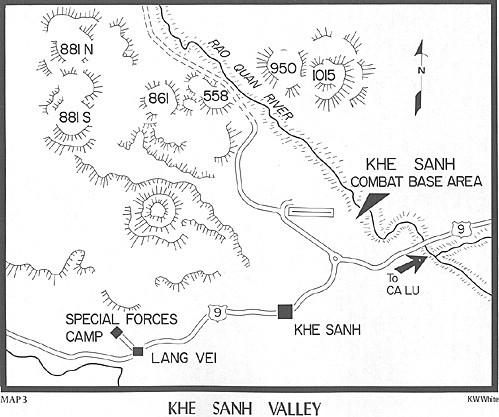

The Khe Sanh Plateau, in western Quang Tri Province, provided the NVA with an excellent alternative, The late Doctor Bernard B. Fall compared the whole of Vietnam to "two rice baskets on opposite ends of a carrying pole." Such being the case, Khe Sanh is located at the pole's fulcrum in the heart of the rugged Annamite Range. Studded with piedmont-type hills, this area provides a natural infiltration route.

Most of the mountain trails are hidden by tree canopies up to 60 feet in height, dense elephant grass, and bamboo thickets. Concealment from reconnaissance aircraft is good, and the heavy jungle undergrowth limits ground observation to five meters in most places. Dong Tri Mountain (1,015 meters high), the highest peak in the region, along with Hill 861 and Hills 881 North and South dominate the two main avenues of approach.(*) ((*) The number indicates the height of the hill in meters.)

One of these, the western access, runs along Route 9 from the Laotian border, throagh the village of Lang Vei to Khe Sanh.

The other is a small valley to the northwest, formed by the Rao Quan River, which runs between Dong Tri Mountain and Hill 861. (See Map 3). Another key terrain feature is Hill 558 which is located squarely in the center of the northwestern approach. The only stumbling block to the NVA in early 1967 was a handful of Marines, U. S. Army Special Forces advisors, and South Vietnamese irregulars. (6) (See Map 3).

The "Green Berets" were the first American troops in the area when, in August 1962, they established a Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) at the same site which later became the Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB). The first Marine unit of any size to visit the area was the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines (1/1) which, in April 1966, was participating in Operation VIRGINIA.

In early October 1966, the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, which was taking part in Operation PRAIRIE, moved into the base and the CIDG camp was relocated near Lang Vei, 9,000 meters to the southwest where it continued surveillance and counter-infiltration operations.

The battalion remained at Khe Sanh with no significant contacts until February 1967 when it was replaced by a single company, E/2/9.(*) ((*) The designation E/2/9 stands for Company E, 2d Battalion, 9th Marines. This type of designation will be used periodically for other Marine units throughout the text.)

In mid-March 1967, Company E became engaged in a heavy action near Hill 861 and Company B, 1/9 moved in to reinforce. After a successful conclusion of the operation, E/2/9 returned to Phu Bai, and B/1/9 remained as the resident defense company.

The KSC3 sat atop a plateau in the shadow of Dong Tri Mountain and overlooked a tributary of the Qaang Tri River. The base had a small dirt airstrip, which had been surfaced by a U. S. Navy Mobile Construction Battalion (Seabees) in the summer of 1966; the field could accommodate helicopters and fixed-wing transport aircraft. Organic artillery support was provided by Battery F, 2/12 (105mm), reinforced by two 155mm howitzers and two 4.2-inch mortars. The Khe Sanh area of operations was also within range of the 175mm guns of the U. S. Army's 2d Battalion, 94th Artillery at Camp Carroll and the Rockpile. In addition to B/1/9 and the CIDG, there was a Marine Combined Action Company (CAC) and a Regional Forces company located in the village of Khe Sanh, approximately 3,500 meters south of the base.(*)

The KSC3 sat atop a plateau in the shadow of Dong Tri Mountain and overlooked a tributary of the Qaang Tri River. The base had a small dirt airstrip, which had been surfaced by a U. S. Navy Mobile Construction Battalion (Seabees) in the summer of 1966; the field could accommodate helicopters and fixed-wing transport aircraft. Organic artillery support was provided by Battery F, 2/12 (105mm), reinforced by two 155mm howitzers and two 4.2-inch mortars. The Khe Sanh area of operations was also within range of the 175mm guns of the U. S. Army's 2d Battalion, 94th Artillery at Camp Carroll and the Rockpile. In addition to B/1/9 and the CIDG, there was a Marine Combined Action Company (CAC) and a Regional Forces company located in the village of Khe Sanh, approximately 3,500 meters south of the base.(*)

((*) The Combined Action Program was designed to increase the ability of the local Vietnamese militia units to defend their own villages. These units, referred to as Popular Forces, were reinforced by groups of Marines who lived, worked, and conducted operations with their Vietnamese counterparts. A Combined Action Company was an organization controlling several Marine squads which served with different Combined Action Platoons. Combined Action Company Oscar (CACO) was the unit operating in the Khe Sanh area. A Regional Forces company was comprised of local South Vietnamese soldiers along with their American and ARVN advisors who were under the operational control of the Vietnamese Province Chief.)

All these units sat astride the northwest-southeast axis of Route 9 and had the mission of denying the NVA a year-round route into eastern Quang Tri Province, The garrison at Khe Sanh and the adjacent outposts commanded the approaches from the west which led to Dong Ha and Quang Tri City. Had this strategic plateau not been in the hands of the Americans, the North Vietnamese would have had an unobstructed invasion route into the two northern provinces and could have outflanked the Allied forces holding the line south of the DMZ.

At that time, the Americans did not possess the helicopter resources, troop strength, or logistical bases in this northern area to adopt a completely mobile type of defense. Therefore, the troops at the KSCB maintained a relatively static defense with emphasis on patrolling, artillery and air interdiction, and occasional reconnaissance in force operations to stifle infiltration through the Khe Sanh Plateau. In the event a major enemy threat developed, General Walt could rapidly reinforce the combat base by air.(7)

On 20 April 1967, the combat assets at KSCB were passed to the operational control of the 3d Marines which had just commenced Operation PRAIRIE IV. The Khe Sanh area of operations was not included as a part of PRAIRIE IV but was the responsibility of the 3d Marines since that regiment was in the best position to oversee the base and reinforce if the need arose. The need arose very soon. (8)

On 24 April 1967, a patrol from Company B, 1/9 became heavily engaged with an enemy force of unknown size north of Hill 861 and in the process prematurely triggered an elaborate North Vietnamese offensive designed to overrun Khe Sanh. What later became known as the "Hill Fights" had begun.

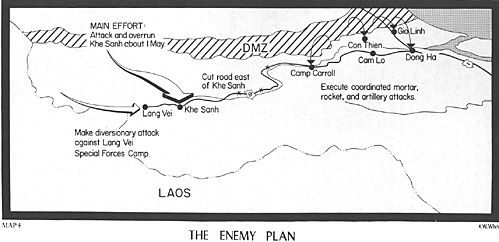

In retrospect, it appears that the drive toward Khe Sanh was but one prong of the enemy's winter-spring offensive, the ultimate objective of which was the capture of Dong Ha, Quang Tri City, and eventually, Hue-Phu Bai.(*)

In retrospect, it appears that the drive toward Khe Sanh was but one prong of the enemy's winter-spring offensive, the ultimate objective of which was the capture of Dong Ha, Quang Tri City, and eventually, Hue-Phu Bai.(*)

((*) The III MAF and enemy operations during the period of the NVA/VC winter-spring offensive (1966-1967) will be the subject of a separate monograph prepared by the Historical Branch.)

That portion of the enemy plan which pertained to Khe Sanh involved the isolation of the base by artillery attacks on the Marine fire support bases in the eastern DMZ area (e.g., Camp Carroll, Con Thien, Gio Linh, etc.).

These were closely coordinated with attacks by fire on the logistical and helicopter installations at Dong Ha and Phu Bai. Demolition teams cut Route 9 between Khe Sanh and Cam Lo to prevent overland reinforcement and, later, a secondary attack was launched against the camp at Lang Vei, which was manned by Vietnamese CIDG personnel and U. S. Army Special Forces advisors. Under cover of heavy fog and low overcast which shrouded Khe Sanh for several weeks, the North Vietnamese moved a regiment into the Hill 881/861 complex and constructed a maze of heavily reinforced bunkers and gun positions from which they intended to provide direct fire against the KSCB in support of their assault troops

. All of these efforts were ancillary to the main thrust--a regimental-sized ground attack--from the 325C NVA Division_ which would sweep in from the west and seize the airfield.(**)(9) (See Map 4).

((**) The diversionary attacks were all launched apparently on schedule. On 27 and 28 April, the previously mentioned Marine fire support and supply bases were hit by some 1,200 rocket, artillery, and mortar rounds. Route 9 was cut in several places. The Special Forces Camp at Lang Vei was attacked and severely mauled on 4 May. Only the main effort was detected and subsequently thwarted.)

The job of stopping the NVA was given to Colonel John P. Lanigan and his 3d Marines. Although he probably did not know it when he arrived at Khe Sanh, this assignment would not be unlike one which 22 years before had earned him a Silver Star on Okinawa. Both involved pushing a fanatical enemy force off a hill.

On 25 April, the lead elements of the 3d Battalion, 3d Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Gary Wilder, arrived at Khe Sanh. The following day, 2/3, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Earl R. De Long, which was taking part in Operation BEACON STAR east of Quang Tri City was airlifted to the combat base. On the 27th, a fresh artillery battery, B/1/12, arrived and reinforced F/2/12; by the end of the day, the two units had been reorganized into an artillery group with one battery in direct support of each battalion.(10)

Late in the afternoon of the 28th, the Marine infantrymen were ready to drive the enemy from the hill masses. These hills formed a near-perfect right triangle with Hill 881 North (N) at the apex and the other two at the base. Hill 861 was the closest to the combat base,some 5,000 meters northwest of the airstrip. Hill 881 South (S) was approximately 3,000 meters west of 861 and 2,000 meters south of 881N.

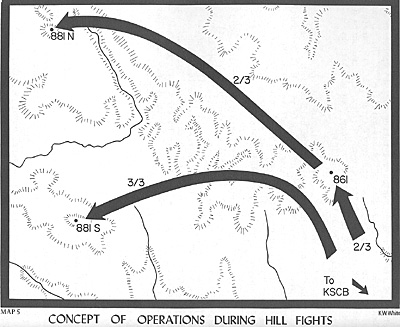

The concept of operations entailed a two-battalion (2/3 and 3/3) assault for which Hill 861 was designated Objective 1; Hill 881S was Objective 2 and Hill 881N was Objective 3. From its position south of Hill 861, 2/3 would assault and seize Objective 1 on 28 April. The 3d Battalion would follow in trace of 2/3 and, after the first objective was taken, 3/3 would wheel to the west, secure the terrain between Hills 861 and 881S, then assault Objective 2 from a northeasterly direction. Coordinated with the 3/3 attack, 2/3 would consolidate its objective then move out toward Hill 881N to screen the right flank of the 3d Battalion and reinforce if necessary. When Objectives 1 and 2 were secured, 3/3 would move to the northwest and support 2/3 while it assaulted Objective 3. (See Map 5).

The concept of operations entailed a two-battalion (2/3 and 3/3) assault for which Hill 861 was designated Objective 1; Hill 881S was Objective 2 and Hill 881N was Objective 3. From its position south of Hill 861, 2/3 would assault and seize Objective 1 on 28 April. The 3d Battalion would follow in trace of 2/3 and, after the first objective was taken, 3/3 would wheel to the west, secure the terrain between Hills 861 and 881S, then assault Objective 2 from a northeasterly direction. Coordinated with the 3/3 attack, 2/3 would consolidate its objective then move out toward Hill 881N to screen the right flank of the 3d Battalion and reinforce if necessary. When Objectives 1 and 2 were secured, 3/3 would move to the northwest and support 2/3 while it assaulted Objective 3. (See Map 5).

After extremely heavy preparatory artillery fires and massive air strikes, the 3d Marines kicked off the attack. On the 28th, 2/3 assaulted and seized Hill 861 in the face of sporadic resistance. Most of the enemy troops had been literally blown from their positions by heavy close air support strikes of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. The operation continued with a thrust against Hill 881S by 3/3. This area was the scene of extremely bitter fighting for several days, because, by this time, the NVA regiment which was originally slated for the attack on the airfield had been thrown into the hill battles in a vain effort to stop the Marines.

After tons of artillery shells and aerial bombs had been employed against the hill, Lieutenant Colonel Wilder's battalion bulled its way to the summit and, on 2 May, secured the objective.

In the meantime, Lieutenant Colonel De Long's battalion pushed along the ridgeline leading from Hill 861 to 881N. After smashing a determined NVA counterattack on 3 May, the 2d Battalion battered its way to the crest of Hill 881N and secured the final objective on the afternoon of the 5th. The three hills belonged to the Marines.(11)

The supporting arms had done a good job, for the top of each hill looked like the surface of the moon. The color of the summit had changed from a vivid green to a dull, ugly brown. All of the lush vegetation had been blasted away, leaving in its place a mass of churned-up dirt and splintered trees. Hundreds of craters dotted the landscape serving as mute witnesses to the terrible pounding that the enemy had taken. What the NVA learned during the operation was something the Marine Corps had espoused for years--that bombs and shells were cheaper than blood.

Thus, the "Hill Fights" ended and the first major attempt by the NVA to take Khe Sanh was thwarted. All intelligence reports indicated that the badly mauled 325C NVA Division had pulled back to lick its wounds, ending the immediate threat in western Quang Tri Province. With the pressure relieved for the time being, General Walt began scaling down his forces at Khe Sanh, because the next phase of the enemy's winter/spring offensive involved a drive through the coastal plain toward Dong Ha.

From 11-13 May, 1/26 moved into the combat base and the adjacent hills to relieve the 3d Marines. By the evening of the 12th, 2/3 had been airlifted to Dong Ha and one artillery battery, B/1/12, was pulled out by convoy. The following day, 3/3 also returned to Dong Ha by truck.

In the meantime, Company A, 1/26, was helilifted to Hill 881S while Company C took up positions on Hill 861. Company B, 1/26, and a skeleton headquarters of the 26th Marines arrived and remained at the base, as did a fresh artillery battery, A/1/13. At 1500 on 13 May, Colonel John J. Padley, Commanding Officer of the 26th Marines, Forward, relieved Colonel Lanigan as the Senior Officer Present at Khe Sanh.(12)

In his analysis of the operation, Colonel Lanigan reported that his men had been engaged in a conventional infantry battle against a well-trained, highly-disciplined, and well-entrenched enemy force. In the past, the NVA had used phantom tactics when engaging U. S. forces--not so at Khe Sanh. The maze of bunker complexes served as a grim reminder of their determination to stay and fight.

They openly challenged the Americans to push them off the hills, and the 3d Marines rose to the occasion. The fierce resistance was overcome by aggressive infantry assaults in coordination with artillery and close air support, which according to Colonel Lanigan was the most accurate and devastating he had witnessed in three wars.

The Communists had anticipated a blood letting and they received one. From 24 April through 12 May 1967, the NVA lost 940 confirmed killed.(*) ((*) Marine losses were 155 killed and 425 wounded.)

Even for the North Vietnamese, this was a massive defeat which could not be easily absorbed. But the leaders in Hanoi were committed to a course of action which traded human lives for strategic expediency. Just like the monsoon rains, the enemy would come again.(13)

Back to Table of Contents -- US Marines: Khe Sanh

Back to Vietnam Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com