After the setbacks at the end of 1813, a lull descended on the northern frontier. In March 1814 Wilkinson made a foray from Plattsburg with about 4,000 men and managed to penetrate about eight miles into Canada before some 200 British and Canadian troops stopped his advance. It was an even more miserable failure than his attempt of the preceding fall.

In early 1814 Congress increased the Army to 45 infantry regiments, 4 regiments of riflemen, 3 of artillery, 2 of light dragoons, and 1 of light artillery. The number of general officers was fixed at 6 major generals and 16 brigadier generals in addition to the generals created by brevet. Secretary of War Armstrong promoted Jacob Brown, who had been commissioned a brigadier general in the Regular Army after his heroic defense of Sackett's Harbor, to the rank of major general and placed him in command of the Niagara-Lake Ontario theater. He also promoted the youthful George Izard to major general and gave him command of the Lake Champlain frontier. He appointed six new brigadier generals from the ablest, but not necessarily most senior, colonels in the Regular Army, among them Winfield Scott, who had distinguished himself at the battle of Queenston Heights and who was now placed in command at Buffalo.

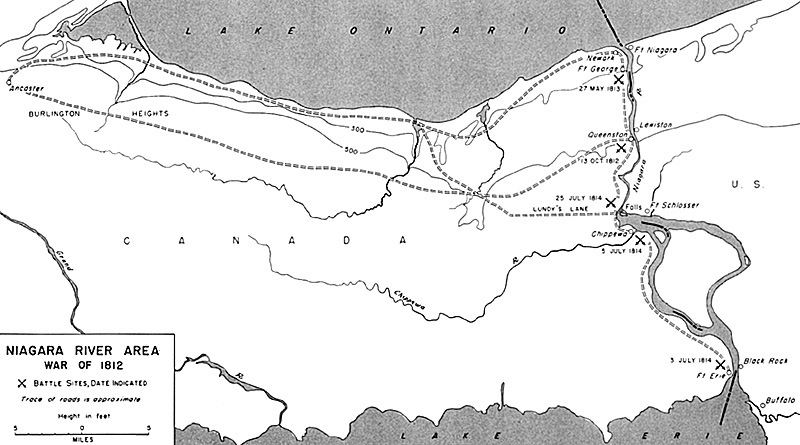

British control of Lake Ontario, won by dint of feverish naval construction during the previous winter, obliged the Secretary of War to recommend operations from Buffalo, but disagreement within the President's cabinet delayed adoption of a plan until June. Expecting Commodore Chauncey's naval force at Sackett's Harbor to be strong enough to challenge the British Fleet, Washington decided upon a co-ordinated attack on the Niagara peninsula.

Secretary Armstrong instructed General Brown to cross the Niagara River in the vicinity of Fort Erie and, after assaulting the fort, either to move against Fort George and Newark or to seize and hold a bridge over the Chippewa River, as he saw fit.

Brown accordingly crossed the Niagara River on July 3 with his force of 3,500 men, took Fort Erie, and then advanced toward the Chippewa River, sixteen miles away. There a smaller British force, including 1,500 Regulars, had gathered to oppose the Americans. General Brown posted his army in a strong position behind a creek with his right flank resting on the Niagara River and his left protected by a swamp. In front of the American position was an open plain, beyond which flowed the Chippewa River; on the other side of the river were the British.

In celebration of Independence Day, General Scott had promised his brigade a grand parade on the plain the next day. On July 5 he formed his troops, numbering about 1,300, but on moving forward discovered British Regulars who had crossed the river undetected, lined up on the opposite edge of the plain. Scott ordered his men to charge and the British advanced to meet them.

The two lines approached each other, alternately stopping to fire and then moving forward, closing the gaps torn by musketry and artillery fire. They came together first at the flanks, while about sixty or eighty yards apart at the center. At this point the British line crumbled and broke. By the time a second brigade sent forward by General Brown reached the battlefield, the British had withdrawn across the Chippewa River and were retreating toward Ancaster, on Lake Ontario. Scott's casualties amounted to 48 killed and 227 wounded; British losses were 137 killed and 304 wounded.

Brown followed the retreating British as far as Queenston, where he halted to await Commodore Chauncey's fleet. After waiting two weeks for Chauncey, who failed to co-operate in the campaign, Brown withdrew to Chippewa. He proposed to strike out to Ancaster by way of a crossroad known as Lundy's Lane, from which he could reach the Burlington Heights at the head of Lake Ontario and at the rear of the British.

Meanwhile the British had drawn reinforcements from York and Kingston, and more troops were on the way from Lower Canada. Sixteen thousand British veterans, fresh from Wellington's victories over the French in Europe, had just arrived in Canada, too late to participate in the Niagara campaign but in good time to permit the redeployment of the troops that had been defending the upper St. Lawrence. By the time General Brown decided to pull back from Queenston, the British force at Ancaster amounted to about 2,200 men under General Phineas Riall; another 1,500 British troops were gathered at Fort George and Fort Niagara at the mouth of the Niagara River.

As soon as Brown began his withdrawal, Riall sent forward about 1,000 men along Lundy's Lane, the very route by which General Brown intended to advance against Burlington Heights; another force of more than 600 British moved out from Fort George and followed Brown along the Queenston road; while a third enemy force of about 400 men moved along the American side of the Niagara River from Fort Niagara.

Riall's advance force reached the junction of Lundy's Lane and the Queenston road on the night of July 24, the same night that Brown reached Chippewa, about three miles distant. Concerned lest the British force on the opposite side of the Niagara cut his line of communications and entirely unaware of Riall's force at Lundy's Lane, General Brown on July 25 ordered Scott to take his brigade back along the road toward Queenston in the hope of drawing back the British force on the other side of the Niagara; but in the meantime that force had crossed the river and joined Riall's men at Lundy's Lane. Scott had not gone far when much to his surprise he discovered himself face-to-face with the enemy.

Lundy's Lane

The ensuing battle, most of which took place after nightfall, was the hardest fought, most stubbornly contested engagement of the war. For two hours Scott attacked and repulsed the counterattacks of the numerically superior British force, which, moreover, had the advantage in position. Then both sides were reinforced. With Brown's whole contingent engaged the Americans now had a force equal to that of the British, about 2,900. They were able to force back the enemy from its position and capture its artillery.

The battle then continued without material advantage to either side until just before midnight, when General Brown ordered the exhausted Americans to fall back to their camp across the Chippewa River. The equally exhausted enemy was unable to follow. Losses on both sides had been heavy, each side incurring about 850 casualties. On the American side, both General Brown and General Scott were severely wounded, Scott so badly that he saw no further service during the war. On the British side, General Riall and his superior, General Drummond, who had arrived with the reinforcements, were wounded, and Riall was taken prisoner.

But sides claimed Lundy's Lane as a victory, as well they might; but Brown's invasion of Canada was halted. Commodore Chauncey, who failed to prevent the British from using Lake Ontario for supply and reinforcements, contributed to the unfavorable outcome. In contrast to the splendid co-operation between Harrison and Perry on Lake Erie, relations between Brown and Chauncey were far from satisfactory. A few days after the Battle of Lundy's Lane the American army withdrew to Fort Erie and held this outpost on Canadian soil until early in November.

Reinforced after Lundy's Lane, the British laid siege to Fort Erie at the beginning of August but were forced to abandon the effort on September 21 after heavy losses. Shortly afterward General Izard arrived with reinforcements from Plattsburg and advanced as far as Chippewa, where the British were strongly entrenched. After a few minor skirmishes, he ceased operations for the winter. The works at Fort Erie were destroyed, and the army withdrew to American soil on November 5.

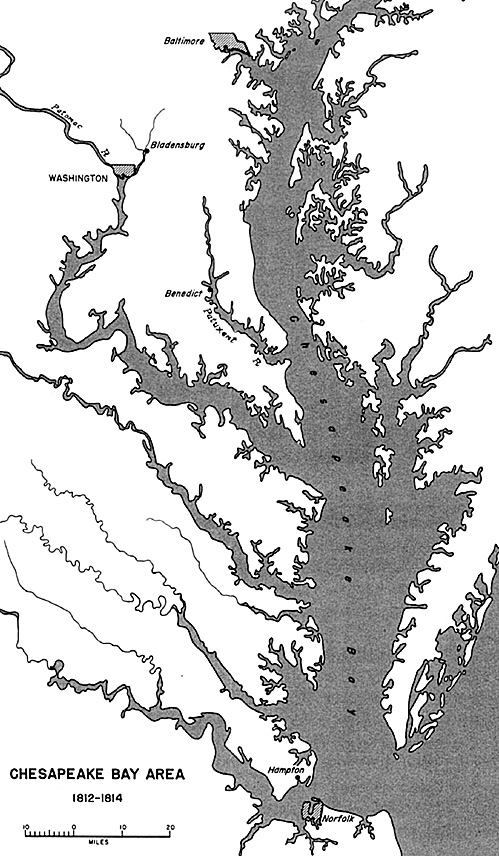

During the summer of 1814 the British had been able to reinforce Canada and to stage several raids on the American coast. Eastport, Maine, on Passamaquoddy Bay, and Castine, at the mouth of the Penobscot River, were occupied without resistance. This operation was something more than a raid since Eastport lay in disputed territory, and it was no secret that Britain wanted a rectification of the boundary. No such political object was attached to British forays in the region of Chesapeake Bay.

Burning of Washington DC

Burning of Washington DC

On August 19 a force of some 4,000 British troops under Maj. Gen. Robert Ross landed on the Patuxent River and marched on Washington. At the Battle of Bladensburg, five days later, Ross easily dispersed 5,000 militia, naval gunners, and Regulars hastily gathered together to defend the Capital. The British then entered Washington, burned the Capitol, the White House, and other public buildings, and returned to their ships.

Baltimore was next on the schedule, but that city had been given time to prepare its defenses. The land approach was covered by a rather formidable line of redoubts, the harbor was guarded by Fort McHenry and blocked by a line of sunken gunboats. On September 13 a spirited engagement fought by Maryland militia, many of whom had run at Bladensburg just two weeks before, delayed the invaders and caused considerable loss, including General Ross, who was killed. When the fleet failed to reduce Fort McHenry, the assault on the city was called off.

Two days before the attack on Baltimore, the British suffered a much more serious repulse on Lake Champlain. After the departure of General Izard for the Niagara front, Brig. Gen. Alexander Macomb had remained at Plattsburg with a force of about 3,300 men. Supporting this force was a small fleet under Commodore Thomas Macdonough.

Back in Canada

Across the border in Canada was an army of British veterans of the Napoleonic Wars whom Sir George Prevost was to lead down the route taken by Burgoyne thirtv-seven years before. Moving slowly up the Richelieu River toward Lake Champlain, he crossed the border and on September 6 arrived before Plattsburg with about 11,000 men. There he waited for almost a week until his naval support was ready to join the attack. With militia reinforcements, Macomb now had about 4,500 men manning a strong line of redoubts and blockhouses that faced a small river. Macdonough had anchored his vessels in Plattsburg Bay, out of range of British guns, but in a position to resist an assault on the American line.

On September 11 the British flotilla appeared and Prevost ordered a joint attack. There was no numerical disparity between the naval forces, but an important one in the quality of the seamen. Macdonough's ships were manned by well-trained seamen and gunners, the British ships by hastily recruited French-Canadian militia and soldiers, with only a sprinkling of regular seamen. As the enemy vessels came into the bay the wind died, and the British were exposed to heavy raking fire from Macdonough's long guns.

The British worked their way in, came to anchor, and the two fleets began slugging at each other, broadside by broadside. At the end the British commander was dead and his ships battered into submission. Prevost immediately called off the land attack and withdrew to Canada the next day.

Macdonough's victory ended the gravest threat that had arisen so far. More important it gave impetus to peace negotiations then under way. News of the two setbacks-Baltimore and Plattsburg-reached England simultaneously, aggravating the war weariness of the British and bolstering the efforts of the American peace commissioners to obtain satisfactory terms.

Back to Table of Contents USAMH Issue 5

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com