The Strategic Pattern

The fundamental strategy was simple enough. The primary undertaking would be the conquest of Canada. The United States also planned an immediate naval offensive, whereby a swarm of privateers and the small Navy would be set loose on the high seas to destroy British commerce. The old invasion route into Canada by way of Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River led directly to the most populous and most important part of the enemy's territory. The capture of Montreal would cut the line of communications upon which the British defense of Upper Canada depended, and the fall of that province would then be inevitable. But this invasion route was near the center of disaffection in the United States, from which little local support could be expected. The west, where enthusiasm for the war ran high and where the Canadian forces were weak, offered a safer theater of operations though one with fewer strategic opportunities.

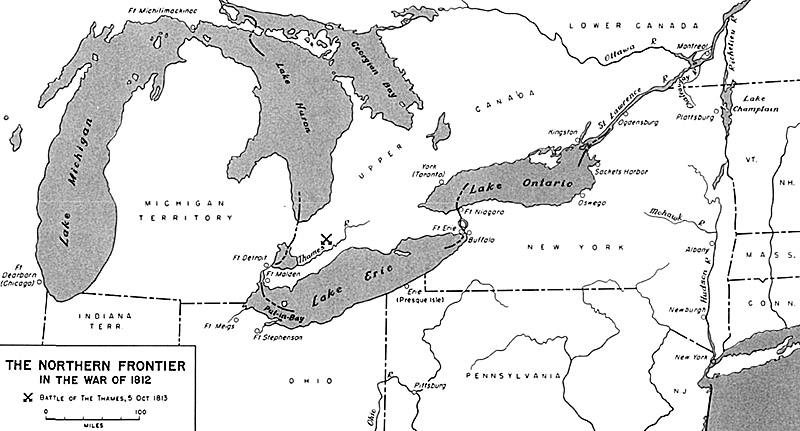

Thus, in violation of the principles of objective and economy of force, the first assaults were delivered across the Detroit River and across the Niagara River between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario.

The war progressed through three distinct stages. In the first, lasting until the spring of 1813, England was so hard pressed in Europe that it could spare neither men nor ships in any great number for the conflict in North America. The United States was free to take the initiative, to invade Canada, and to send out cruisers and privateers against enemy shipping. During the second stage, lasting from early 1813 to the beginning of 1814, England was able to establish a tight blockade but still could not materially reinforce the troops in Canada.

In this stage the American Army, having gained experience, won its first successes. The third stage, in 1814, was marked by the constant arrival in North America of British Regulars and naval reinforcements, which enabled the enemy to raid the North American coast almost at will and to take the offensive in several quarters. At the same time, in this final stage of the war, American forces fought their best fights and won their most brilliant victories.

The First Campaigns

The first blows of the war were struck in the Detroit area and at Fort Michilimackinac. President Madison gave Brig. Gen. William Hull, governor of the Michigan Territory, command of operations in that area. Hull arrived at Fort Detroit on July 5, 1812,with a force of about 1,500 Ohio militiamen and 300 Regulars, which he led across the river into Canada a week later. At that time the whole enemy force on the Detroit frontier amounted to about 150 British Regulars, 300 Canadian militiamen, and some 250 Indians led by Tecumseh. Most of the enemy were at Fort Malden, about twenty miles south of Detroit, on the Canadian side of the river.

General Hull had been a dashing young officer in the Revolution, but by this time age and its infirmities had made him cautious and timid. Instead of moving directly against Fort Malden, Hull issued a bombastic proclamation to the people of Canada and stayed at the river landing almost opposite Detroit. He sent out several small raiding detachments along the Thames and Detroit Rivers, one of which returned after skirmishing with the British outposts near Fort Malden. In the meantime General Brock, who was both energetic and daring, sent a small party of British Regulars, Canadians, and Indians across the river from Malden to cut General Hull's communications with Ohio.

By that time Hull was discouraged by the loss of Fort Michilimackinac, whose sixty defenders had quietly surrendered on July 17 to a small group of British Regulars supported by a motley force of fur traders and Indians that, at Brock's suggestion, had swiftly marched from St. Joseph Island, forty miles to the north. Hull also knew that the enemy in Fort Malden had received reinforcements (which he overestimated tenfold) and feared that Detroit would be completely cut off from its base of supplies.

On August 7 he began to withdraw his force across the river into Fort Detroit. The last American had scarcely returned before the first men of Brock's force appeared and began setting up artillery opposite Detroit. By August 15 five guns were in position and opened fire on the fort, and the next morning Brock led his troops across the river. Before Brock could launch his assault, the Americans surrendered. Militiamen were released under parole; Hull and the Regulars were sent as prisoners to Montreal. Later paroled, Hull returned to face a court-martial for his conduct of the campaign, was sentenced to be shot, and was immediately pardoned.

On August 15, the day before the surrender, the small garrison at distant Fort Dearborn, acting on orders from Hull, had evacuated the post and started out for Detroit. The column was almost instantly attacked by a band of Indians who massacred the Americans before returning to destroy the fort.

With the fall of Michilimackinac, Detroit, and Dearborn, the entire territory north and west of Ohio fell under enemy control. The settlements in Indiana lay open to attack, the neighboring Indian tribes hastened to join the winning side, and the Canadians in the upper province lost some of the spirit of defeatism with which they had entered the war.

Immediately after taking Detroit, Brock transferred most of his troops to the Niagara frontier where he faced an American invasion force of 6,500 men. Maj. Gen. Stephen van Rensselaer, the senior American commander and a New York militiaman, was camped at Lewiston with a force of goo Regulars and about 2,300 militiamen. Van Rensselaer owed his appointment not to any active military experience, for he had none, but to his family's position in New York. Inexperienced as be was in military art, van Rensselaer at least fought the enemy, which was more than could be said of the Regular Army commander in the theater, Brig. Gen. Alexander Smyth. Smyth and his 1,650 Regulars and nearly 400 militiamen were located at Buffalo. The rest of the American force, about 1,300 Regulars, was stationed at Fort Niagara.

Van Rensselaer planned to cross the narrow Niagara River and capture Queenston and its heights, a towering escarpment that ran perpendicular to the river south of the town. From this vantage point he hoped to command the area and eventually drive the British out of the Niagara peninsula. Smyth, on the other hand, wanted to attack above the falls, where the banks were low and the current less swift, and he refused to co-operate with the militia general. With a force ten times that of the British opposite him, van Rensselaer decided to attack alone. After one attempt had been called off for lack of oars for the boats, van Rensselaer finally ordered an attack for the morning of October 13.

The assault force numbered 600 men, roughly half New York militiamen; but several boats drifted beyond the landing area, and the first echelon to land, numbering far less than 500, was pinned down for a time on the river bank below the heights until the men found an unguarded path, clambered to the summit, and, surprising the enemy, overwhelmed his fortified battery and drove him down into Queenston.

The Americans repelled a hastily formed counterattack later in the morning, during which General Brock was killed. This, however, was the high point of van Rensselaer's fortunes. Although 1,300 men were successfully ferried across the river under persistent British fire from a fortified battery north of town, less than half of them ever reached the American line on the heights. Most of the militiamen refused to cross the river, insisting on their legal right to remain on American soil, and General Smyth ignored van Rensselaer's request for Regulars. Meanwhile, British and Canadian reinforcements arrived in Queenston, and Maj. Gen. Roger Sheaffe, General Brock's successor, began to advance on the American position with a force of 800 troops and 300 Indian skirmishers. Van Rensselaer's men, tired and outnumbered, put up a stiff resistance on the heights but in the end were defeated with 300 Americans were killed or wounded and nearly 1,000 were captured.

After the defeat at Queenston, van Rensselaer resigned and was succeeded by the unreliable Smyth, who spent his time composing windy proclamations. Disgusted at being marched down to the river on several occasions only to be marched back to camp again, the new army that had assembled after the battle of Queenston gradually melted away. The men who remained lost all sense of discipline, and finally at the end of November the volunteers were ordered home and the Regulars were sent into winter quarters. General Smyth's request for leave was hastily granted, and three months later his name was quietly dropped from the Army rolls.

Except for minor raids across the frozen St. Lawrence, there was no further fighting along the New York frontier until the following spring. During the Niagara campaign the largest force then under arms, commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry Dearborn, had been held in the neighborhood of Albany, more than 250 miles from the scene of operations. Dearborn had had a good record in the Revolutionary War and had served as Jefferson's Secretary of War. Persuaded to accept the command of the northern theater, except for Hull's forces, he was in doubt for some time about the extent of his authority over the Niagara front. When it was clarified he was reluctant to exercise it. Proposing to move his army, which included seven regiments of Regulars with artillery and dragoons, against Montreal in conjunction with a simultaneous operation across the Niagara River, Dearborn was content to wait for his subordinates to make the first move.

When van Rensselaer made his attempt against Queenston, Dearborn, who was still in the vicinity of Albany, showed no sign of marching toward Canada.

At the beginning of November he sent a large force north to Plattsburg and announced that he would personally lead the army into Montreal, but most of his force got no farther than the border. When his advanced guard was driven back to the village of Champlain by Canadian militiamen and Indians, and his Vermont and New York volunteers flatly refused to cross the border, Dearborn quietly turned around and marched back to Plattsburg, where he went into winter quarters.

If the land campaigns of 18T2 reflected little credit on the Army, the war at sea brought lasting glory to the infant Navy. Until the end of the year the American frigates, brigs-of-war, and privateers were able to slip in and out of harbors and cruise almost at will, and in this period they won their most brilliant victories. At the same time, American privateers were picking off English merchant vessels by the hundreds. Having need of American foodstuffs, Britain was at first willing to take advantage of New England's opposition to the war by not extending the blockade to the New England coast, but by the beginning of 1814 it was effectively blockading the whole coast and had driven most American naval vessels and privateers off the high seas.

Back to Table of Contents USAMH Issue 5

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com