In the reduction of March 1802 Congress cut back the total strength of the Army to 3,220 men, approximately what it had been in 1797 when Adams took office. It was more than 50 percent stronger in artillery, but the more expensive cavalry was eliminated.

Congress also abolished the Office of the Quartermaster General when it reduced the size of the Army and in its place instituted a system of contract agents. It divided the country into three military departments with a military agent in each who, with his assistants, was responsible for the movement of supplies and troops within his department. Since the assistant agents were also appointed by the President, the three military agents had no way to enforce accountability on their subordinates. This system soon led to large property losses.

Since the Revolution the Army had suffered from a lack of trained technicians, particularly in engineering science, and had depended largely upon foreign experts. As a remedy Washington, Knox, Hamilton, and others had recommended the establishment of a military school. During Washington's administration, Congress had added the rank of cadet in the Corps of Artillerists and Engineers with two cadets assigned to each company for instruction.

But not until the Army reorganization of 1802 did Congress create a separate Corps of Engineers, consisting of 10 cadets and 7 officers, and assign it to West Point to serve as the staff of a military academy. Within a few years the U.S. Military Academy became a center of study in military science and a source of trained officers. By 1812 it listed 89 graduates, 65 of them still serving in the Army and playing an important role in operations and the construction of fortifications.

The Army and Westward Expansion

The Army and Westward Expansion

Not long after Thomas Jefferson became President, rumors reached America that France had acquired Louisiana from Spain. The news was upsetting. Many Americans, including Jefferson, had believed that when Spain lost its weak hold on the colonies the United States would automatically fall heir to them. But, with a strong power like France in possession, it was useless to wait for the colonies to fall into the lap of the United States. The presence of France in North America also raised a new security problem. Up to this time the problem of frontier defense had been chiefly one of pacifying the Indians, keeping the western territories from breaking away, and preventing American settlers from molesting the Spanish.

Now, with a strong, aggressive France as backdoor neighbor, the frontier problem became tied up with the question of security against possible foreign threats. The transfer of Louisiana to France also marked the beginning of restraints on American trade down the Mississippi. In the past, Spain had permitted American settlers to send their goods down the river and to deposit them at New Orleans. just before transferring the colony, however, it revoked the American right of deposit, an action which made it almost impossible for Americans to send goods out by this route.

These considerations persuaded Jefferson in 1803 to inquire about the possibility of purchasing New Orleans from France. When Napoleon, anticipating the renewal of the war in Europe, offered to sell the whole of Louisiana, Jefferson quickly accepted, suddenly doubling the size of the United States.

The Army, after taking formal possession of Louisiana on December 20, 1803, established small garrisons at New Orleans and the other former Spanish posts on the lower Mississippi. Jefferson later appointed Brig. Gen. James Wilkinson, who had survived the various reorganizations of the Army to become senior officer, first governor of the new territory.

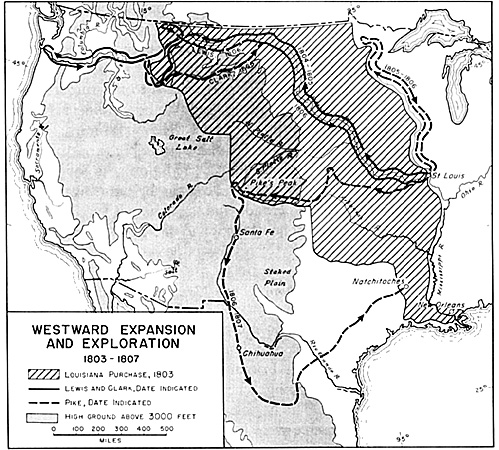

Before the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson had persuaded Congress to support an exploration of the unknown territory west of the Mississippi. The acquisition of this territory now made such an exploration even more desirable. To lead the expedition, Jefferson chose Capt. Meriwether Lewis and Lt. William Clark, both of whom had served under General Wayne in the Northwest. Leaving St. Louis in the spring of 18o4 with twenty-seven men, Lewis and Clark traveled up the Missouri River, crossed the Rocky Mountains, and followed the Columbia River down to the Pacific, which they reached after much hardship in November 1805. On the return journey, the party explored the region of central Montana and returned to St. Louis in September 1806.

While Lewis and Clark were exploring beyond the Missouri, General Wilkinson sent out Capt. Zebulon M. Pike on a similar expedition to the headwaters of the Mississippi. In 1807 Wilkinson organized another expedition. This time he sent twenty men under Captain Pike westward into what is now Colorado. After exploring the region around the peak that bears his name, Pike encountered some Spaniards who, resentful of the incursion, escorted his party to Santa Fe. From there the Spanish took the Americans into Mexico and then back across Texas to Natchitoches, once more in American territory. The Lewis and Clark expedition and those of Captain Pike contributed much to the geographic and scientific knowledge of the country, and today remain as great epics of the West.

To march across the continent might seem the manifest destiny of the Republic, but it met with an understandable reaction from the Spanish. The dispute over the boundary between Louisiana and Spain's frontier provinces and the question of the two Floridas became burning issues during Jefferson's second administration. Tension mounted in 1806 as rumors reached Washington of the dispatch of thousands of Spanish Regulars to reinforce the mounted Mexican militiamen in east Texas. Jefferson reacted to the rumors by calling up the Orleans and Mississippi Territories' militia and sending approximately 1,000 Regulars to General Wilkinson to counter the Spanish move.

The rumors proved unfounded; at no time did the Spanish outnumber the American forces in the area. A series of cavalry skirmishes occurred along the Sabine River, but the opposing commanders prudently avoided war by agreeing to establish a neutral zone between the Arroyo Hondo and the Sabine River. The two armies remained along this line throughout 1806, and the neutral zone served as a de facto boundary until 1812.

Back to Table of Contents USAMH Issue 4

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com