On September 24, 1783, four days after the signing of the Treaty of Paris formally ended the war, Congress directed General Washington to discharge "such parts of the Federal Army now in Service as he shall deem proper and expedient."

For the time being Washington retained the force facing the British at New York, discharging the rest of the Continentals. After the British quit New York, he kept only one infantry regiment and a battalion of artillery, 600 men in all, to guard the military supplies at West Point and other posts.

The period leading up to this demobilization was a stormy one for the Congress. During the winter of 1782 the Army had grown impatient, and rumors that it would take matters into its own hands gained credence when several anonymous addresses were circulated among the officers at Newburgh urging them not to fight if the war continued or not to lay down their arms if peace were declared and their pay accounts left unsettled. In an emotional speech to his old comrades, Washington disarmed this threat. He promised to intercede for them, and in the end, Congress did give in to the officers' demands, agreeing to award the men their back pay and to grant the officers full pay for five years in lieu of half pay for life.

Demobilization then proceeded peacefully, but it was against the background of these demands and threats that Congress wrestled with a major postwar problem, the size and character of the peacetime military establishment. In the way of most governments, Congress turned the problem over to a committee, this one under Alexander Hamilton, to study the facts and make recommendations for a military establishment.

The Question of a Peacetime Army

Congress subscribed to the prevailing view that the first line of defense should be a "well-regulated and disciplined militia sufficiently armed and accoutered." Its reluctance to create a standing army was understandable; a permanent army would be a heavy expense, and it would complicate the struggle between those who wanted a strong national government and those who preferred the existing loose federation of states.

Further, the recent threats of the Continental officers strengthened the popular fear that a standing army might be used to coerce the states or become an instrument of despotism.

General Washington, to whom Hamilton's committee turned first for advice, echoed the prevailing view. He pointed out that a large standing army in time of peace had always been considered "dangerous to the liberties of a country" and that the nation was "too poor to maintain a standing army adequate to our defense." The question might also be considered, he continued, whether any surplus funds that became available should not better be applied to "building and equipping a Navy without which, in case of War we could neither Protect our Commerce, nor yield that assistance to each other which, on such an extent of seacoast, our mutual safety would require."

He believed that America should rely ultimately on an improved version of the historic citizens' Militia, a force enrolling all males between 18 and 50 liable for service to the nation in emergencies. He also recommended a volunteer militia, recruited in units, periodically trained, and subject to United States rather than state control. At the same time Washington did suggest the creation of a small Regular Army to awe the Indians, protect our Trade, prevent the encroachment of our Neighbors of Canada and the Floridas, and guard us at least from surprises; also for security of our magazines." He recommended a force of four regiments of infantry and one of artillery, totaling 2,630 officers and men.

Hamilton's committee also listened to suggestions made by General von Steuben, Major General Louis le Beque Du Portail, Chief Engineer of the Army, and Benjamin Lincoln, Secretary at War. On June 18, 1783, it submitted a plan to Congress similar to Washington's, but with a more ambitious militia program. Congress, however, rejected the proposal. Sectional rivalries, constitutional questions, and, above all, economic objections were too strong to be overcome.

The committee thereupon revised its plan, recommending an even larger army that it hoped to provide at less expense by decreasing the pay of the regimental staff officers and subalterns. Washington when asked admitted that detached service along the frontiers and coasts would probably require more men than he had proposed, but he disagreed that a larger establishment could be provided more economically than the one he had recommended.

A considerable number of the delegates to Congress had similar misgivings, and when the committee presented its revised report on October 23, Congress refused to accept it. During the winter of 1783 the matter rested. Under the Articles of Confederation an affirmative vote of the representatives of nine states was required for the exercise of certain important powers, including military matters, and on few occasions during this winter were enough states represented for Congress to renew the debate.

In the spring of 1784, the question of a permanent peacetime army became involved in the politics of state claims to western lands. The majority of men in the remaining infantry regiment and artillery battalion were from Massachusetts and New Hampshire, and those states ' wanted to be rid of the financial burden of providing the extra pay that they had promised the men on enlistment. Congress refused to assume the responsibility unless the New England states would vote for a permanent military establishment.

The New England representatives, led by Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, insisted that Congress had no authority to maintain a standing army, but at the same time they wanted the existing troops to occupy the western forts, situated in land claimed by the New England states. New York vigorously contested the New England claims to western lands, particularly in the region around Oswego and Niagara, and refused to vote for any permanent military establishment unless Congress gave it permission to garrison the western forts with its own forces.

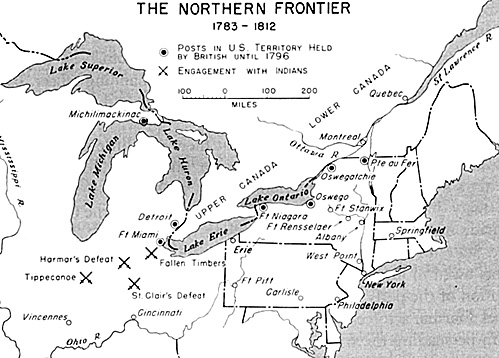

The posts that had been the object of concern and discussion dominated the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. Located on American territory south of the boundary established by the peace treaty of 1783, the posts were in the hands of British troops when the war ended, but by the terms of the treaty they were to be turned over to the United States as speedily as possible. Congress agreed that a force should be retained to occupy the posts as soon as the British left.

The problem was how and by whom the troops were to be raised. A decision was all the more urgent because the government was in the midst of negotiating a treaty with the Indians of the Northwest, and, as Washington had suggested, a sizable force "to awe the Indians" would facilitate the negotiations. hut the deadlock between the New England states and New York continued until early June 1784

Finally, on the last two days of the session, Congress rushed through a compromise. It ordered the existing infantry regiment and battalion of artillery disbanded, except for 80 artillerymen retained to guard military stores at West Point and Fort Pitt. It tied this discharge to a measure providing for the immediate recruitment of a new force of 700 men, a regiment of eight infantry and two artillery companies, which was to become the nucleus of a new Regular Army.

By not making requisitions on the states for troops, but merely recommending that the states provide them from their militia, Congress got rid of most of the New England opposition on this score; by not assigning a quota for Massachusetts and New Hampshire, Congress satisfied the objections of most of the other states.

Four states were called upon to furnish troops: 260 men from Pennsylvania 165 from Connecticut, 165 from New York, and 110 from New Jersey. Lt. Col Josiah Harmar of Pennsylvania was appointed commanding officer. By the end of September 1784 only New Jersey and Pennsylvania had filled their quotas by enlisting volunteers from their militia.

Congress had meanwhile learned that there was little immediate prospect that the British would evacuate the frontier posts. Canadian fur traders and the settlers in Upper Canada had objected so violently to this provision of the peace treaty that the British Government secretly directed the Governor-General of Canada not to evacuate the posts without further orders. The failure of the United States to comply with a stipulation in the treaty regarding the recovery of debts owed to loyalists provided the British with an excuse to postpone the evacuation of the posts for twelve more years.

So the New Jersey contingent of Colonel Harmar's force was sent to Fort Stanwix, in upstate New York, to assist in persuading the Iroquois to part with their lands, while the remainder of the force moved to Fort Maclntosh, thirty miles down the Ohio River from Fort Pitt, where similar negotiations were carried on with the Indians of the upper Ohio.

Back to Table of Contents USAMH Issue 4

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com