As Howe and Burgoyne went their separate ways in 1777, seemingly

determined to satisfy only their personal ambitions, so Clinton and Cornwallis in 1781 paved the road to Yorktown by their disagreements and lack of coordination. Clinton was Cornwallis' superior in this case, but the latter enjoyed the confidence of Germain to an extent that Clinton did not. Clinton, believing that without large reinforcements the British could not operate far from coastal bases, had opposed Cornwallis' ventures in the interior of the Carolinas, and when Cornwallis came to Virginia he did so without even informing his superior of his intention.

As Howe and Burgoyne went their separate ways in 1777, seemingly

determined to satisfy only their personal ambitions, so Clinton and Cornwallis in 1781 paved the road to Yorktown by their disagreements and lack of coordination. Clinton was Cornwallis' superior in this case, but the latter enjoyed the confidence of Germain to an extent that Clinton did not. Clinton, believing that without large reinforcements the British could not operate far from coastal bases, had opposed Cornwallis' ventures in the interior of the Carolinas, and when Cornwallis came to Virginia he did so without even informing his superior of his intention.

Since 1779 Clinton had sought to paralyze the state of Virginia by conducting raids up its great rivers, arousing the Tories, and establishing a base in the Chesapeake Bay region.

He thought this base might eventually be used as a starting point for one arm of a pincers movement against Pennsylvania for which his own idle force in New York would provide the other. A raid conducted in the Hampton Roads area in 1779 was highly successful, but when Clinton sought to follow it up in 1780 the force sent for the purpose had to be diverted to Charleston to bail Cornwallis out after King's Mountain.

Finally in 1781 he got an expedition into Virginia, a contingent of 1,600 under the American traitor, Benedict Arnold. In January Arnold conducted a destructive raid up the James River all the way to Richmond. His presence soon proved to be a magnet drawing forces of both sides to Virginia.

In an effort to trap Arnold, Washington dispatched Lafayette to Virginia with 1,200 of his scarce Continentals and persuaded the French to send a naval squadron from Newport to block Arnold's escape by sea. The plan went awry when a British fleet drove the French squadron back to Newport and Clinton sent another 2,600 men to Virginia along with a new commander, Maj. Gen. William Phillips. Phillips and Arnold continued their devastating raids, which Lafayette was too weak to prevent. Then on May 20 Cornwallis arrived from Wilmington and took over from Phillips. With additional reinforcements sent by Clinton he was able to field a force of about 7,000 men, approximately a quarter of the British strength in America. Washington sent down an additional reinforcement of 800 Continentals under General Wayne, but even with Virginia militia Lafayette's force remained greatly outnumbered.

Cornwallis and Clinton were soon working at cross-purposes. Cornwallis proposed to carry out major operations in the interior of Virginia, but Clinton saw as little practical value in this tactic as Cornwallis did in Clinton's plan to establish a base in Virginia for a pincers movement against Pennsylvania. Cornwallis at first turned to the interior and engaged in a fruitless pursuit of Lafayette north of Richmond.

Then, on receiving Clinton's positive order to return to the coast, establish a base, and return part of his force to New York, Cornwallis moved back down the Virginia peninsula to take up station at Yorktown, a small tobacco port on the York River just off Chesapeake Bay. In the face of Cornwallis' insistence that he must keep all his troops with him, Clinton vacillated, reversing his own orders several times and in the end granting Cornwallis, request. Lafayette and Wayne followed Cornwallis cautiously down the peninsula, lost a skirmish with him at Green Spring near Williamsburg on July 6, and finally took up a position of watchful waiting near Yorktown.

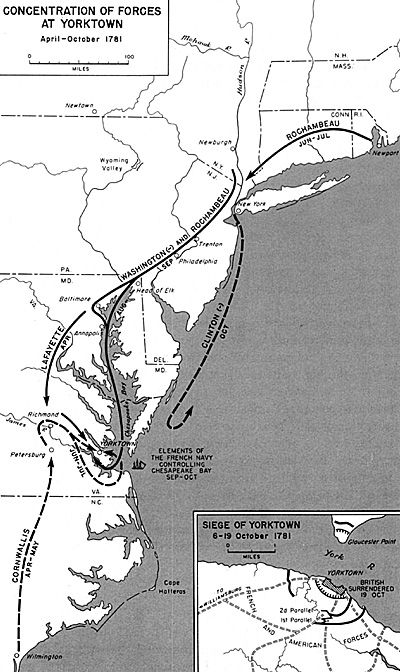

Meanwhile, Washington had been trying to persuade the French to co- operate in a combined land and naval assault on New York in the summer of 1781. Rochambeau brought his 4,000 troops down from Newport in April and placed them under Washington's command. The prospects were still bleak since the combined Franco-American force numbered but 10,000 against Clinton's 17,000 in well-fortified positions.

Then on August 14 Washington learned that the French Fleet in the West Indies, commanded by Admiral Francois de Grasse, would not come to New York but would arrive in the Chesapeake later in the month and remain there until October 15. He saw immediately that if he could achieve a superior concentration of force on the land side while de Grasse still held the bay he could destroy the British army at Yorktown before Clinton had a chance to relieve it.

The movements that followed illustrate most effectively a successful application of the principles of the offensive, surprise, objective, mass, and maneuver. Even without unified command of Army and Navy forces, Franco- American co-operation this time was excellent. Admiral Louis, Comte de Barras, immediately put out to sea from Newport to join de Grasse. Washington sent orders to Lafayette to contain Cornwallis at Yorktown and then, after making a feint in the direction of New York to deceive Clinton, on August 21 started the major portion of the Franco-American Army on a rapid secret movement to Virginia, via Chesapeake Bay, leaving only 2,000 Americans behind to watch Clinton.

On August 30, while Washington was on the move southward, de Grasse arrived in the Chesapeake with his entire fleet of twenty-four ships of the line and a few days later debarked 3,000 French troops to join Lafayette. Admiral Thomas Graves, the British naval commander in New York, meanwhile had put out to sea in late August with nineteen ships of the line, hoping either to intercept Barras' squadron or to block de Grasse's entry into the Chesapeake. He failed to find Barras, and when he arrived off Hampton Roads on September 5 he found de Grasse already in the bay.

The French admiral sallied forth to meet Graves and the two fleets fought an indecisive action off the Virginia capes. Yet for all practical purposes the victory lay with the French for, while the fleets maneuvered at sea for days following the battle, Barras' squadron slipped into the Chesapeake and the French and American troops got past into the James River. Then de Grasse got back into the bay and joined Barras, confronting Graves with so superior a naval force that he decided to return to New York to refit.

SURRENDER OF CORNWALLIS

SURRENDER OF CORNWALLIS

When Washington's army arrived on September 26, the French Fleet was in firm control of the bay, blocking Cornwallis' sea route of escape. A decisive concentration had been achieved. Counting 3,000 Virginia militia, Washington had a force of about 9,000 Americans and 6,000 French troops with which to conduct the siege. It proceeded in the best traditions of Vauban under the direction of French engineers.

Cornwallis obligingly abandoned his forward position on September 30, and on October 6 the first parallel was begun 600 yards from the main British position. Artillery placed along the trench began its destructive work on October 9. By October 11 the zigzag connecting trench had been dug 200 yards forward, and work on the second parallel had begun. Two British redoubts had to be reduced in order to extend the line to the York River. This accomplished, Cornwallis' only recourse was escape across the river to Gloucester Point where the American line was thinly held. A storm on the night of October 16 frustrated his attempt to do so, leaving him with no hope but relief from New York. Clinton had been considering such relief for days, but he acted too late.

On the very day, October 17, that Admiral Graves set sail from New York with a reinforced fleet and 7,000 troops for the relief of Yorktown, Cornwallis began negotiations on terms of surrender. On October 19 his entire army marched out to lay down its arms, the British band playing an old tune called "The World Turned Upside Down."

So far as active campaigning was concerned, Yorktown ended the war. Both Greene and Washington maintained their armies in position near New York and Charleston for nearly two years more, but the only fighting that occurred was some minor skirmishing in the South. Cornwallis' defeat led to the overthrow of the British cabinet and the formation of a new government that decided the war in America was lost. With some success, Britain devoted its energies to trying to salvage what it could in the West Indies and in India. The independence for which Americans had fought thus virtually became a reality when Cornwallis' command marched out of its breached defenses at Yorktown.

Back to Table of Contents Issue 3

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com