It was the frontier militia assembling "when they were about to be attacked in their own homes" who struck the blow that actually marked the turning point in the south. Late in 1780, with Clinton's reluctant consent, Cornwallis set out on the invasion of North Carolina. He sent Maj. Patrick Ferguson, who had successfully organized the Tories in the upcountry of South Carolina, to move north simultaneously with his "American Volunteers," spread the Tory gospel in the North Carolina back country, and join the main army at Charlotte with a maximum number of recruits.

Ferguson's advance northward alarmed the "over-mountain men" in western North Carolina, southwest Virginia, and what is now east Tennessee. A picked force of mounted militia riflemen gathered on the Catawba River in western North Carolina, set out to find Ferguson, and brought him to bay at King's Mountain near the border of the two Carolinas on October 7. In a battle of patriot against Tory (Ferguson was the only British soldier present), the patriots' triumph was complete. Ferguson himself was killed and few of his command escaped death or capture. Some got the same "quarter" Tarleton had given Buford's men at the Waxhaws.

King's Mountain was as fatal to Cornwallis' plans as Bennington had been to those of Burgoyne. The North Carolina Tories, cowed by the fate of their compatriots, gave him little support. The British commander on October 14, 1780, began a wretched retreat in the rain back to Winnsboro, South Carolina, with militia harassing his progress. Clinton was forced to divert an expedition of 2,500 men sent to establish a base in Virginia to reinforce Cornwallis.

The frontier militia had turned the tide, but having done so, they returned to their homes. To keep it moving against the British was the task of the new commander, General Greene. When Greene arrived at Charlotte, North Carolina, early in December 1780, he found a command that consisted of 1,500 men fit for duty, only 949 of them Continentals.

The army lacked clothing and provisions and had little systematic means of procuring them. Greene decided that he must not engage Cornwallis' army in battle until he had built up his strength, that he must instead pursue delaying tactics to wear down his stronger opponent. The first thing he did was to take the unorthodox step of dividing his army in the face of a superior force, moving part under his personal command to Cheraw Hill, and sending the rest under Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan west across the Catawba over 100 miles away. It was an intentional violation of the principle of mass. Greene wrote:

- I am well satisfied with the movement .... It makes the most of my inferior force, for it compels

my adversary to divide his, and holds him in doubt as to his own line of conduct. He cannot leave Morgan behind him to come at me, or his posts at Ninety-Six and Augusta would be exposed. And he cannot chase Morgan far, or prosecute his views upon Virginia, while I am here with the whole country open before me. I am as near to Charleston as he is, and as near Hillsborough as I was at Charlotte; so that I am in no danger of being cut off from my reinforcements.

Left unsaid was the fact that divided forces could live off the land much easier than one large force and constitute two rallying points for local militia instead of one. Greene was, in effect, sacrificing mass to enhance maneuver.

Cornwallis, an aggressive commander, had determined to gamble everything on a renewed invasion of North Carolina. Ignoring Clinton's warnings, he depleted his Charleston base by bringing almost all his supplies forward. In the face of Greene's dispositions, Cornwallis divided his army into not two but three parts. He sent a holding force to Camden to contain Green, directed Tarleton with a fast-moving contingent of 1,100 infantry and cavalry to find and crush Morgan, and with the remainder of his army moved cautiously up into North Carolina to cut off any of Morgan's force that escaped Tarleton.

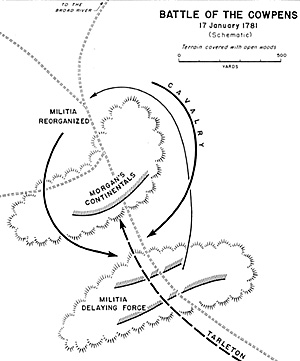

Tarleton caught up with Morgan on January 17, 1781, west of King's Mountain at a place called the Cowpens, an open, sparsely forested area six miles from the Broad River.

Battle of Cowpens

Battle of Cowpens

Morgan chose this site to make his stand less by design than necessity, for he had intended to get across the Broad. Nevertheless, on ground seemingly better suited to the action of Regulars, he achieved a little tactical masterpiece, making the most effective use of his heterogeneous force, numerically equal to that of Tarleton but composed of three-fourths militia.

Selecting a hill as the center of his position, he placed his Continental infantry on it, deliberately leaving his flanks open. Well out in front of the main line he posted militia riflemen in two lines, instructing the first line to fire two volleys and then fall back on the second, the combined line to fire until the British pressed them, then to fall back to the rear of the Continentals and re-form as a reserve.

Behind the hill he placed Lt. Col. William Washington's cavalry detachment, ready to charge the attacking enemy at the critical moment. Every man in the ranks was informed of the plan of battle and the part he was expected to play in it.

On finding Morgan, Tarleton ordered an immediate attack. His men moved forward in regular formation, were momentarily checked by the militia rifles, but, taking the retreat of the first two lines to be the beginning of a rout, rushed headlong into the steady fire of the Continentals on the hill. When the British were well advanced, the American cavalry struck them on the right flank and the militia, having re-formed, charged out from behind the hill to hit the British left. Caught in a clever double envelopment, the British surrendered after suffering heavy losses. Tarleton managed to escape with only a small force of cavalry he had held in reserve. It was on a small scale, and with certain significant differences, a repetition of the classic double envelopment of the Romans by a Carthaginian army under Hannibal at Cannae in 216 B.C., an event of which Morgan, no reader of books, probably had not the foggiest notion.

Having struck his fatal blow against Tarleton, Morgan still had to move fast to escape Cornwallis. Covering ioo miles and crossing two rivers in five days, he rejoined Greene early in February. Cornwallis by now was too heavily committed to the campaign in North Carolina to withdraw. Hoping to match the swift movement of the Americans, he destroyed all his superfluous supplies, baggage, and wagons and set forth in pursuit of Greene's army. The American general retreated, through North Carolina, up into southern Virginia, then back into North Carolina again, keeping just far enough in front of his adversary to avoid battle with Cornwallis' superior force.

Finally on March 15, 1781, at Guilford Court House in North Carolina, on ground he had himself chosen, Greene halted and gave battle. By this time he had collected 1,500 Continentals and 3,000 militia to the 1,900 Regulars the British could muster. The British held the field after a hard-fought battle, but suffered casualties of about one-fourth of the force engaged. It was, like Bunker Hill, a Pyrrhic victory. His ranks depleted and his supplies exhausted, Cornwallis withdrew to Wilmington on the coast, and then decided to move northward to join the British forces General Clinton had sent to Virginia.

Greene, his army in better condition than six months earlier, pushed quickly into South Carolina to reduce the British posts in the interior. He fought two battles--at Hobkirk's Hill on April 25, and at Eutaw Springs on September 8--losing both but with approximately the same results as at Guilford Court House.

One by one the British interior posts fell to Greene's army, or to militia and partisans. By October 1781 the British had been forced to withdraw to their port strongholds along the coast-Charleston and Savannah. Greene had lost battles, but won a campaign. In so doing, he paved the way for the greater victory to follow at Yorktown.

Back to Table of Contents Issue 3

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com