Late in 1778 the British began to turn their main effort to the south. Tory strength was greater in the Carolinas and Georgia and the area was closer to the West Indies, where the British Fleet had to stand guard against the French. The king's ministers hoped to bring the southern states into the fold one by one, and from bases there to strangle the recalcitrant north. A small British force operating from Florida quickly overran thinly populated Georgia in the winter of 1778-79.

Late in 1778 the British began to turn their main effort to the south. Tory strength was greater in the Carolinas and Georgia and the area was closer to the West Indies, where the British Fleet had to stand guard against the French. The king's ministers hoped to bring the southern states into the fold one by one, and from bases there to strangle the recalcitrant north. A small British force operating from Florida quickly overran thinly populated Georgia in the winter of 1778-79.

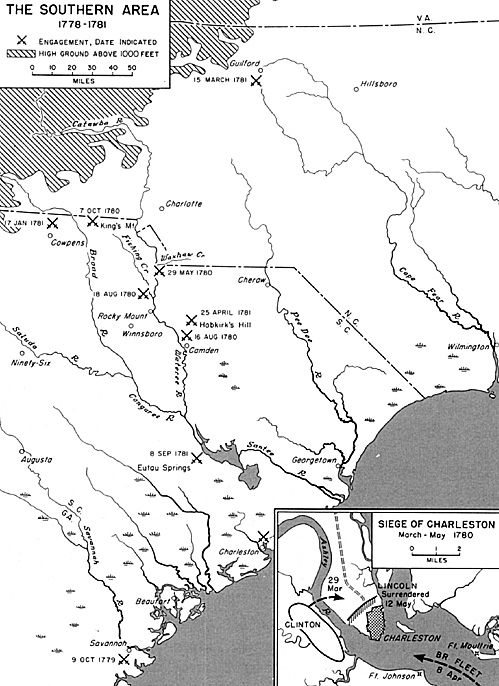

Alarmed by this development, Congress sent General Benjamin Lincoln south to Charleston in December 1778 to command the Southern Army and organize the southern effort. Lincoln gathered 3,500 Continentals and militiamen, but in May 1779, while he maneuvered along the Georgia border, the British commander, Maj. Gen. Augustine Prevost, slipped around him to lay siege to Charleston. The city barely managed to hold out until Lincoln returned to relieve it.

In September 1779 d'Estaing arrived off the coast of Georgia with a strong French Fleet and 6,000 troops. Lincoln then hurried south with 1,350 Americans to join him in a siege of the main British base at Savannah. Unfortunately, the Franco-American force had to hurry its attack because d'Estaing was unwilling to risk his fleet in a position dangerously exposed to autumn storms.

The French and Americans mounted a direct assault on Savannah on October 9, abandoning their plan to make a systematic approach by regular parallels. The British in strongly entrenched positions repulsed the attack in what was essentially a Bunker Hill in reverse, the French and Americans suffering staggering losses. D'Estaing then sailed away to the West Indies, Lincoln returned to Charleston, and the second attempt at Franco-American co-operation ended in much the same atmosphere of bitterness and disillusion as the first.

Meanwhile Clinton, urged on by the British Government, had determined to push the southern campaign in earnest. In October 1779 he withdrew the British garrison from Newport, pulled in his troops from outposts around New York, and prepared to move south against Charleston with a large part of his force. With d'Estaing's withdrawal the British regained control of the sea along the American coast, giving Clinton a mobility that Washington could not match.

While Clinton drew forces from New York and Savannah to achieve a decisive concentration of force (14,000 men) at Charleston, Washington was able to send only piecemeal reinforcements to Lincoln over difficult overland routes. Applying the lessons of his experience in 1776, Clinton this time carefully planned a co-ordinated Army-Navy attack. First, he landed his force on John's Island to the south, then moved up to the Ashley River, investing Charleston from the land side. Lincoln, under strong pressure from the South Carolina' authorities, concentrated his forces in a citadel defense on the neck of land between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, leaving Fort Moultrie in the harbor lightly manned.

On April 8 British warships successfully forced the passage past Moultrie, investing Charleston from the sea. The siege then proceeded in traditional eighteenth century fashion, and on May 12, 1780, Lincoln surrendered his entire force of 5,466 men, the greatest disaster to befall the American cause during the war. Meanwhile, Col. Abraham Buford with 350 Virginians was moving south to reinforce the garrison. Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton with a force of British cavalry took Buford by surprise at the Waxhaws, a district near the North Carolina border, and slaughtered most of his men, refusing to honor the white flag Buford displayed.

After the capture of Charleston, Clinton returned to New York with about a third of his force, leaving General Cornwallis with 8,000 men to follow up the victory. Cornwallis established his main seaboard bases at Savannah, Beaufort, Charleston, and Georgetown, and in the interior extended his line of control along the Savannah River westward to Ninety-Six and northward to Camden and Rocky Mount. Cornwallis' force, however, was too small to police so large an area, even with the aid of the numerous Tories who took to the field.

Though no organized Continental force remained in the Carolinas and Georgia, American guerrillas, led by Brig. Gens. Thomas Sumter and Andrew Pickens and Lt. Col. Francis Marion, began to harry British posts and lines of communications and to battle the bands of Tories. A bloody, ruthless, and confused civil war ensued, its character determined in no small degree by Tarleton's action at the Waxhaws. In this way, as in the Saratoga campaign, the American grass roots strength began once again to assert itself and to deny the British the fruits of military victory won in the field.

On June 22, 1780, two more understrength Continental brigades from Washington's army arrived at Hillsboro, North Carolina, to form the nucleus of a new Southern Army around which militia could rally and which could serve as the nerve center of guerrilla resistance. In July Congress, without consulting Washington, provided a commander for this army in the person of General Gates, the hero of Saratoga.

Gates soon lost his northern laurels. Gathering a force of about 4,000 men, mostly militia, he set out to attack the British post at Camden, South Carolina. Cornwallis hurried north from Charleston with reinforcements and his army of 2,200 British Regulars made contact with Gates outside Camden on the night of August 15. In the battle, that ensued the following morning, Gates deployed his militia on the left and the Continentals under Maj. Gen. Johann de Kalb on the right. The militia were still forming in the hazy dawn when Cornwallis struck, and they fled in panic before the British onslaught. De Kalb's outnumbered Continentals put up a valiant but hopeless fight.

Tarleton's cavalry pursued the fleeing Americans for 30 miles, killing or making prisoner those who lagged. Gates himself fled too fast for Tarleton, reaching Hillsboro, 160 miles away, in three days. There he was able to gather only about 800 survivors of the Southern Army. To add to the disaster, Tarleton caught up with General Sumter, whom Gates had sent with a detachment to raid a British wagon train, and virtually destroyed his force in a surprise attack at Fishing Creek on August 18. Once more South Carolina seemed safely in British hands.

Nadir of the American Cause

In the summer of 1780 the American cause seemed to be at as low an ebb as it had been after the New York campaign in 1776 or after the defeats at Ticonderoga and Brandywine in 1777. Defeat in the south was not the only discouraging aspect of patriot affairs.

In the north a creeping paralysis had set in as the patriotic enthusiasm of the early war years waned. The Continental currency had virtually depreciated out of existence, and Congress was impotent to pay the soldiers or purchase supplies. At Morristown, New Jersey, in the winter of 1779-80 the army suffered worse hardships than at Valley Forge. Congress could do little but attempt to shift its responsibilities onto the states, giving each the task of providing clothing for its own troops and furnishing certain quotas of specific supplies for the entire Army. The system of "specific supplies" worked not at all. Not only were the states laggard in furnishing supplies, but when they did it was seldom at the time or place they were needed. This breakdown in the supply system was more than even General Greene, as Quartermaster General, could cope with, and in early 1780, under heavy criticism in Congress, he resigned his position.

Under such difficulties, Washington had to struggle to hold even a small Army together. Recruiting of Continentals, difficult to begin with, became almost impossible when the troops could neither be paid nor supplied adequately and had to suffer such winters as those at Morristown.

Enlistments and drafts from the militia in 1780 produced not quite half as many men for one year's service as had enlisted in 1776 for three years or the duration. While recruiting lagged, morale among those men who had enlisted for the longer terms naturally fell. Mutinies in 1780 and 1781 were suppressed only by measures of great severity.

Germain could write confidently to Clinton: "so very contemptible is the rebel force now . . . that no resistance . . . is to be apprehended that can materially obstruct . . . the speedy suppression of the rebellion . . . the American levies in the King's service are more in number than the whole of the enlisted troops in the service of the Congress." The French were unhappy. In the summer of 1780 they occupied the vacated British base at Newport, moving in a naval squadron and 4,000 troops under the command of Lieutenant General the Comte de Rochambeau.

Rochambeau immediately warned his government: "Send us troops, ships and money, but do not count on these people nor on their resources, they have neither money nor credit, their forces exist only momentarily, and when they are about to be attacked in their own homes they assemble . . . to defend themselves." Another French commander thought only one highly placed American traitor was needed to decide the campaign.

Clinton had, in fact, already found his "highly placed traitor" in Benedict Arnold, the hero of the march to Quebec, the naval battle on the lakes, Stanwix, and Saratoga. "Money is this man's God," one of his enemies had said of Arnold earlier, and evidently he was correct. Lucrative rewards promised by the British led to Arnold's treason, though he evidently resented the slights Congress had dealt him, and he justified his act by claiming that the Americans were now fighting for the interests of Catholic France and not their own.

Arnold wangled an appointment as commander at West Point and then entered into a plot to deliver this key post to the British. Washington discovered the plot on September 21, 1780, just in time to foil it, though Arnold himself escaped to become a British brigadier.

Arnold's treason in September 1780 marked the nadir of the patriot cause. In the closing months of 1780, the Americans somehow put together the ingredients for a final and decisive burst of energy in 1781. Congress persuaded Robert Morris, a wealthy Philadelphia merchant, to accept a post as Superintendent of Finance, and Col. Timothy Pickering, an able administrator, to replace Greene as Quartermaster General. Greene, as Washington's choice, was then named to succeed Gates in command of the Southern Army. General Lincoln, exchanged after Charleston, was appointed Secretary at War and the old board was abolished.

Morris took over many of the functions previously performed by unwieldy committees. Working closely with Pickering, he abandoned the old paper money entirely and introduced a new policy of supplying the army by private contracts, using his personal credit as eventual guarantee for payment in gold or silver. It was an expedient but, for a time at least, it worked.

Back to Table of Contents Issue 3

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com