The name of Valley Forge has come to stand, and rightly so, as a patriotic symbol of suffering, courage, and perserverance. The hard core of 6,000 Continentals who stayed with Washington during that bitter winter of 1777-78 indeed suffered much. Some men had no shoes, no pants, no blankets. Weeks passed when there was no meat and men were reduced to boiling their shoes and eating them. The wintry winds penetrated the tattered tents that were at first the only shelter.

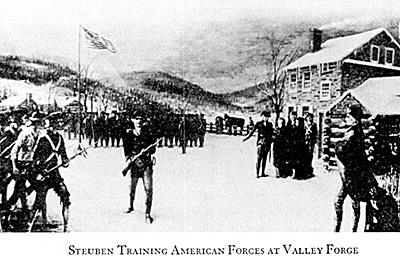

STEUBEN TRAINING AMERICAN FORCES AT VALLEY FORGE

The symbolism of Valley Forge should not be allowed to obscure the fact that the suffering was largely unnecessary. While the soldiers shivered and went hungry, food rotted and clothing lay unused in depots throughout the country. True, access to Valley Forge was difficult, but little determined effort was made to get supplies into the area. The supply and transport system broke down.

In mid-1777, both the Quartermaster and Commissary Generals resigned along with numerous subordinate officials in both departments, mostly merchants who found private trade more lucrative. Congress, in refuge at York, Pennsylvania, and split into factions, found it difficult to find replacements. If there was not, as most historians now believe, an organized cabal seeking to replace Washington with Gates, there were many, both in and out of the Army, who were dissatisfied with the Commander in Chief, and much intrigue went on.

Gates was made president of the new Board of War set up in 1777, and at least two of its members were enemies of Washington. In the administrative chaos at the height of the Valley Forge crisis, there was no functioning Quartermaster General at all.

Washington weathered the storm and the Continental Army was to emerge from Valley Forge a more effective force than before. With his advice, Congress instituted reforms in the Quartermaster and Commissary Departments that temporarily restored the effectiveness of both agencies. Washington's ablest subordinate, General Greene, reluctantly accepted the post of Quartermaster General. The Continental Army itself gained a new professional competence from the training given by the Prussian, Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben.

Steuben appeared at Valley Forge in February 1778 arrayed in such martial splendor that one private thought he had seen Mars, the god of war, himself. He represented himself as a baron, a title he had acquired in the service of a small German state, and as a former lieutenant general on the staff of Frederick the Great, though in reality he had been only a captain. The fraud was harmless, for Steuben had a broad knowledge of military affairs and his remarkable sense of the dramatic was combined with the common touch a true Prussian baron might well have lacked.

Washington had long sensed the need for uniform training and organization, and after a short trial he secured the appointment of Steuben as Inspector General in charge of a training program. Steuben carried out the program during the late winter and early spring of 1778, teaching the Continental Army a simplified but effective version of the drill formations and movements of European armies, proper care of equipment, and the use of the bayonet, a weapon in which British superiority had previously been marked. He attempted to consolidate the understrength regiments and companies and organized light infantry companies as the elite force of the Army. He constantly sought to impress upon the officers their responsibility for taking care of the men.

Steuben never lost sight of the difference between the American citizen soldier and the European professional. He early noted that American soldiers had to be told why they did things before they would do them well, and he applied this philosophy in his training program. His trenchant good humor and vigorous profanity, almost the only English he knew, delighted the Continental soldiers and made the rigorous drill more palatable. After Valley Forge, Continentals would fight on equal terms with British Regulars in the open field.

First Fruits of the French Alliance

While the Continental Army was undergoing its ordeal and transformation at Valley Forge, Howe dallied in Philadelphia, forfeiting whatever remaining chance he had to win a decisive victory before the effects of the French alliance were felt. He had had his fill of the American war and the king accepted his resignation from command, appointing General Clinton as his successor.

As Washington prepared to sally forth from Valley Forge, the British Army and the Philadelphia Tories said goodbye to their old commander in one of the most lavish celebrations ever held in America, the Mischianza, a veritable Belshazzar's feast. The handwriting on the wall appeared in the form of orders already in Clinton's hands, to evacuate the American capital. With the French in the war, England had to look to the safety of the long ocean supply line to America and to the protection of its possessions in other parts of the world. Clinton's orders were to detach 5,000 men to the West Indies and 3,000 to Florida, and to return the rest of his army to New York by sea.

As Clinton prepared to depart Philadelphia, Washington had high hopes that the war might be won in 1778 by a co-operative effort between his army and the French Fleet. The Comte d'Estaing with a French naval squadron of eleven ships of the line and transports carrying 4,000 troops left France in May to sail for the American coast. D'Estaing's fleet was considerably more powerful than any Admiral Howe could immediately concentrate in American waters. For a brief period in 1778 the strategic initiative passed from British hands, and Washington hoped to make full use of it.

Clinton had already decided, before he learned of the threat from d'Estaing, to move his army overland to New York prior to making any detachments, largely because he could find no place for 3,000 horses on the transports.

On June 18, 1778, he set out with about 10,000 men. Washington, who by that time had gathered about 12,000, immediately occupied Philadelphia and then took up the pursuit of Clinton, undecided as to whether he should risk an attack on the British column while it was on the march. His Council of War was divided, though none of his generals advised a "general action." The boldest Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne, and the young major general, the Marquis de Lafayette, urged a "partial attack" to strike at a portion of the British Army while it was strung out on the road; the most cautious, General Lee, who had been exchanged and had rejoined the army at Valley Forge, advised only guerrilla action to harass the British columns.

On June 26 Washington decided to take a bold approach, though he issued no orders indicating an intention to bring on a "general action." He sent forward an advance guard composed of almost half his army to strike at the British rear when Clinton moved out of Monmouth Court House on the morning of June 27. Lee, the cautious, claimed the command from Lafayette, the bold, when he learned the detachment would be so large.

In the early morning, Lee advanced over rough ground that had not been reconnoitered and made contact with the British rear, but Clinton reacted quickly and maneuvered to envelop the American right flank. Lee, feeling that his force was in an untenable position, began a retreat that became quite confused.

Washington rode up amidst the confusion and, exceedingly irate to find the advance guard in retreat, exchanged harsh words with Lee. He then assumed direction of what had to be a defense against a British counterattack. The battle that followed, involving the bulk of both armies, lasted until nightfall on a hot, sultry day with both sides holding their own.

For the first time the Americans fought well with the bayonet as well as with the musket and rifle, and their battlefield behavior generally reflected the Valley Forge training. Nevertheless, Washington failed to strike a telling blow at the British Army, for Clinton slipped away in the night and in a few days completed the retreat to New York. Lee demanded and got a court-martial at which he was judged, perhaps unjustly, guilty of disobedience of orders, poor conduct of the retreat, and disrespect for the Commander in Chief. As a consequence he retired from the Army, though the controversy over his actions at Monmouth was to go on for years.

Washington, meanwhile, sought his victory in co-operation with the French Fleet. D'Estaing arrived off the coast on July 8 and the two commanders at first agreed on a combined land and sea attack on New York, but d'Estaing feared he would be unable to get his deep-draft ships across the bar that extended from Staten Island to Sandy Hook, in order to get at Howe's inferior fleet. They then decided to transfer the attack to the other and weaker British stronghold at Newport, Rhode Island--a city standing on an island with difficult approaches.

A plan was agreed on whereby the French Fleet would force the passage on the west side of the island and an American force under General Sullivan would cross over and mount an assault from the east. The whole scheme soon went awry. The French Fleet arrived off Newport on July 29 and successfully forced the passage; Sullivan began crossing on the east on August 8 and d'Estaing began to disembark his troops.

Unfortunately at this juncture Admiral Howe appeared with a reinforced British Fleet, forcing d'Estaing to re-embark his troops and put out to sea to meet Howe. As the two fleets maneuvered for advantage, a great gale scattered both on August 12. The British returned to New York to refit, and the French Fleet to Boston, whence d'Estaing decided he must move on to tasks he considered more pressing in the West Indies. Sullivan was left to extricate his forces from an untenable position as best he could, and the first experiment in Franco-American co-operation came to a disappointing end with recriminations on both sides.

The fiasco at Newport ended any hopes for an early victory over the British as a result of the French alliance. By the next year, as the French were forced to devote their major attention to the West Indies, the British regained the initiative on the mainland, and the war entered a new phase.

The New Conditions of the War

After France entered the war in 1778, it rapidly took on the dimensions of a major European as well as an American conflict. In 1779 Spain declared war against England, and in the following year Holland followed suit. The necessity of fighting European enemies in the West Indies and other areas and of standing guard at home against invasion weakened the British effort against the American rebels. Yet the Americans were unable to take full advantage of Britain's embarrassments, for their own effort suffered more and more from war weariness, lack of strong direction, and inadequate finance.

Moreover, the interests of European states fighting Britain did not necessarily coincide with American interests. Spain and Holland did not ally themselves with the American states at all, and even France found it expedient to devote its major effort to the West Indies. Finally, the entry of ancient enemies into the fray spurred the British to intensify their effort and evoked some, if not enough, of that characteristic tenacity that has produced victory for England in so many wars. Despite their many new commitments, the British were able to maintain in America an army that was usually superior in numbers to the dwindling Continental Army, though never strong enough to undertake offensives again on the scale of those of 1776 and 1777

Monmouth was the last general engagement in the north between Washington's and Clinton's armies. In 1779 the situation there became a stalemate and remained so until the end of the war. Washington set up a defense system around New York with its center at West Point, and Clinton made no attempt to attack his main defense line. The British commander did, in late spring 1779, attempt to draw Washington into the open by descending in force on unfinished American outpost fortifications at Verplanck's Point and Stony Point, but Washington refused to take the bait.

When Clinton withdrew his main force to New York, the American commander retaliated by sending Maj. Gen. Anthony Wayne on July 15, 1779, with an elite corps of light infantry, on a stealthy night attack on Stony Point, a successful action more notable for demonstrating the proficiency with which the Americans now used the bayonet than for any important strategic gains. Wayne was unable to take Verplanck's, and Clinton rapidly retook Stony Point. Thereafter the war around New York became largely an affair of raids, skirmishes, and constant vigilance on both sides.

Clinton's inaction allowed Washington to attempt to deal with British-inspired Indian attacks. Although Burgoyne's defeat ended the threat of invasion from Canada, the British continued to incite the Indians all along the frontier to bloody raids on American settlements. From Fort Niagara and Detroit they sent out their bands, usually led by Tories, to pillage, scalp, and burn in the Mohawk Valley of New York, the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania, and the new American settlements in Kentucky.

In August 1779 Washington detached General Sullivan with a force to deal with the Iroquois in Pennsylvania and New York. Sullivan laid waste the Indians' villages and defeated a force of Tories and Indians at Newtown on August 29.

In the winter of 1778-79, the state of Virginia had sponsored an expedition that struck a severe blow at the British and Indians in the northwest. Young Lt. Col. George Rogers Clark with a force of only 175 men, ostensibly recruited for the defense of Kentucky, overran all the British posts in what is today Illinois and Indiana. Neither he nor Sullivan, however, was able to strike at the sources of the trouble-Niagara and Detroit. Indian raids along the frontiers continued, though they were somewhat less frequent and severe.

Back to Table of Contents Issue 3

Back to US Army Military History List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com